My earliest memory of the word okada is of a time in 2001. I am fairly certain it was the year after my father moved us to the new house in Mushin from the old one in Surulere.

Our new street was dirty. Rats cat-walked past immobile cars while their engines revved, signaling the struggle to free themselves from the gaping potholes that covered every foot of the road. In the rainy season, these potholes would house brown water and the kids would jump in them and smile.

A walk from one side of the street to the other would leave your nostrils flooded with the stench of piss. The stench was the kind that choked your throat and stung your eyes and made you scrunch up your nose and hold your breath till you were safely in your own house.

In all this filth the people lived, thrived and fought.

In our former neighborhood, there never used to fights. The last altercation in our former street was between a Landlord and his tenant over rent increase, and this was done in the presence of lawyers. There was never any blood.

On our new street, blood was spilled whenever one person disagreed with another. Our new neighbors made a lot of noise. If it was not a missing broom, it was a mysteriously broken bucket.

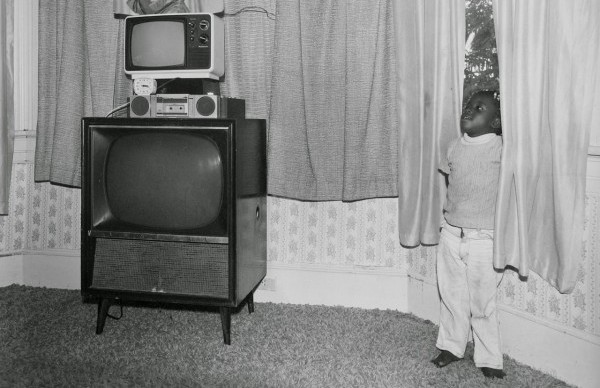

I do not remember there being any quiet time except at 8pm on Thursdays. Thursday nights were the most quiet in our neighborhood. A friend in Uganda will later tell me that it was the same there too, but on Tuesdays. The roads would be clear and families would be seated, eyes glued to their television screens, sometimes eating, sometimes not. Super Story was on.

I remember it was dark outside and the characteristic quietness of Thursdays had descended on all the households. Crickets were the only ones who dared to speak, and even they chirped with a certain restraint on days like this. We were all seated in the small room that we chose to call a parlor. The ceiling fan, as it spun, slowly, made it hard to hear the words of the man speaking on the television, so my father turned it off. The room soon became hot, but it was worth it.

It was one of those episodes based on true life stories—I loved those. The man’s voice was all we could hear. His silhouette was the only thing on the screen as he narrated, through sobs, the beginning of his encounter. The actors were going to take over from him at some point and depict what he had narrated. My hand found their way to the plate of ukwa beside me and guided a few boluses safely back to my mouth. My father had brought back the roasted breadfruit seeds from his last trip to the village. It—the trip—was for a meeting to contribute money for my uncle’s burial. My father did not tell us this. I found out last week when he was talking to my mother.

“Gladys, I don’t like this thing. These my umunna want to kill me.” My father had sounded close to tears.

It was usually late in the night when they had talks like these. When they were sure we were all asleep. I never slept early. Some nights I never slept. When my parents noticed once and questioned me, I blamed it on my sister Chika. Her incessant snoring was not the real reason for my sleeplessness but each night, as I stared at the gaping hole in the ceiling of our little room, each grunt followed by a nasal sigh started to get very annoying. Chika did not talk to me for days after that because my mother had given her a serious talk, detailing how she was not supposed to snore as a lady. The talk took a serious turn when my mother put it to us, my father and me as we stared, that the snoring was caused by Chika’s excessive playing during the daytime and proceeded to ban her from playing till further notice. That was the first time I doubted my mother’s words. I had heard her, my mother, snoring only a few days ago, and I knew, for a fact, that she never played. She always turned down my high-pitched invitations. “Come and play with us mommy!” “Another time” always followed soon after. I continued asking and “another time” became like the response to each verse of a psalm, like we did at church.

“Kedu ihe me, what happened?” my mother responded and her words sounded like hugs. The consolation that followed the words made you want to forget what you were angry about and just let her hold you. It was the same way she would tell me “Ndo, my big boy” when I had to take injections and for a moment it would work and all would be right in the world, that is until the needle pricked my skin, at which point, I would resume my wails.

“You know I told you they called for a meeting concerning my brother’s burial.”

“Ehen? Yes?”

“I got there, and these people ambushed me. They told me that I would contribute the largest amount since I am living in the city.”

“City kwa? What is city about where we are staying?”

“I don’t know o. I really don’t.”

“Do they want to kill you? Did you kill him? Tufia! Nna m sorry o. Ndo. It …” She stopped mid-sentence when she heard a loud clap.

My hand had responded to a mosquito helping itself to blood from my thighs. The resulting sound startled even me. I heard my mother’s legs hit the floor, so I started the longest race to my bed.

Safe under my blanket, I heard the sound of the door creak. It creaked because it was hanging by one hinge. My mother walked around the room with a kerosene lamp. I held my breath and prayed she would not hear my heart beating, even over the sound of Chika’s ground-moving snore. My mother walked over to Chika and tapped her on her arm. Silence returned to the room, and my heartbeat seemed a little too loud. I finally let myself breathe when she left. That was when I noticed the pain. I had bumped my knee on the wooden frame on the side of the bed

My mother was not home when we started watching Super Story. She had left for the market earlier that day to get ugwu leaves to cook oha soup. The other soup, egusi, the one she’d cooked four days before, had finished. The show had just started, and the man playing the narrator was frantically running on a sidewalk in a familiar part of Lagos. It looked a lot like the sidewalk beside my school.

A knock on the door was the most irritating thing in any house when Super Story was on. One wondered who it could possibly be and why the person wasn’t in their own house by this time. The worst part was that someone had to stand up and open the door for the intruder, hence missing a part of that episode, no matter how little. The knock on our door that night was an urgent one. I started to stand up before my father told me to sit down. It was already dark, and my parents always said that Chika, who was older than me with two years, was supposed to go to the door when it was this late.

“My friend go and open the door!” My father screamed at Chika. ‘My friend’ was not said with affection. It carried all the maliciousness in the world. Chika walked slowly to the door, trying to view some more of the episode. This irritated my father. I sat there with a mouth full of ukwa, thankful that it was not me.

The door that led into our tiny flat swung open after Chika unlocked it, almost knocking her down. Two men were on either side of my mother. Both her arms were around their necks. Only one of her legs was touching the floor. My father’s hairy legs hit the floor as he stood to help these men put my mother down on the threadbare couch. Tears were on my mother’s face. Her leg was red from blood oozing out of a burn wound.

I noticed all these at one glance and turned to face the TV right after. I turned back to face them when I heard Chika crying. She was seated on the couch and holding my mother’s right hand while my father held the left. My father thanked the young men profusely and asked me to lock the door after them. I locked the door with haste, twisting the key in the lock only once, instead of twice and returned to my position on the rug in front of the television. Something was about to happen to the narrator’s wife. I could tell because the music had changed. It had gotten eerie and sad.

“… and the okada fell on my leg and the silencer burned me o!” My mother did not say these words in succession. They were interrupted, torn apart by sniffs and inhalation and coughs.

I had never seen her cry. I had seen my father cry, once before, when his new Siemens phone was stolen at the banking hall. He had come home that day blubbering. It would have been a funny sight had it not been my father—the disciplinarian, the strict man, the hard guy. I would later understand that phones and SIM cards were not as cheap at the time as they would become later that decade. It had been a big deal. My father lost his job at the Ministry of works a few months after that. It was at that point, it seemed, that all the dominoes started falling. That was when we had to move to this street. To begin this life. This life where my father had no phone anymore.

“Chika oya stop crying and go and call Nurse.” My father’s voice was a few octaves lower. He sounded subdued, like tears were stinging his eyes and begging to flow down his rough, spot-ridden face.

Nurse was our neighbor. Her flat was just beside ours. Just as torn apart. She locked her door with a padlock when she left for her shifts due to a broken lock that the caretaker swore was not there until she moved in. The caretaker lied a lot. We had seen the door unlocked and broken at the locks when we had moved in, two months before Nurse did.

Nurse was a heavyset woman with an annoying laugh. Annoying because she laughed anyhow, without reason sometimes. Most of the time. I was not always happy when she announced her presence at our door because she, for some reason, was given to touching and tugging my cheeks till they felt hot, like I’d been slapped. She was a friend of the family nonetheless and was very helpful with medical advice when we needed it but could not afford to go to the hospital. We paid her in kind, usually during Christmas, when my mother would cook ofe akwu served with white rice. Nurse would usually come around, without invitation of course, and we would all eat. Her laugh was more annoying when we ate. Pieces of beef and half-eaten grains of rice would fly out of her mouth as she recounted tales of the lazy security guard at the hospital. Throughout, the story would be interrupted by bouts of laughter—hers alone because no one else was laughing. I heard my mother say that that was why no man wanted to marry her, that she was lousy. She said it late at night, to my father. I was not supposed to be listening.

“Daddy, she is not around.” Chika was back and her eyes were dry now. Disappointment sat on her eyebrows. Soon it was on my father’s face too. I could not see my mother’s face. It was buried in my father’s chest. The sobbing had reduced, and her breathing was slow and subdued. She looked like she was asleep.

“Nnamdi leave that TV and come and tell your mother sorry!” He meant to whisper, but it did not come out that way. He stretched his neck, and his veins were frighteningly prominent when he did.

My hands were below me, and they raised me up. I was soon beside my mother. My father sent Chika to get some iodine from his room, and he watched me as my small hands moved up and down my mother’s back in slow circular motions while my mouth said “Sorry mummy.” But my eyes stayed on the television. After it started to feel like my soothing had been appreciated by my mother, I returned to my seat in front of the television screen and there was soon ukwa in my mouth.

“Ihe a ga e gbu nwaa.” My father whispered to my mother. This thing will kill this child.

My obsession with Super Story was the thing to which he referred. It was the first time I doubted my father’s words.

Many things could kill me, especially on this street, but not Super Story, never Super Story. The episode was over soon and as I dozed off, my head on the rug, the smell of iodine stung my nose, my mother’s muffled screams followed by my father’s soothing “sorry”s entered my subconscious and the taste of ukwa, on my tongue, lingered.

*********

Image by Baldwin Lee via Manufactoriel

About the Author:

Edwin Madu is a Nigerian writer born in Lagos. His work has appeared on naijastories.com, africanwriter.com and he blogs at www.mytheoryoflife.wordpress.com. He was one of the selected participants at the 2015 Farafina Trust Creative Writing Workshop.

Edwin Madu is a Nigerian writer born in Lagos. His work has appeared on naijastories.com, africanwriter.com and he blogs at www.mytheoryoflife.wordpress.com. He was one of the selected participants at the 2015 Farafina Trust Creative Writing Workshop.

bola389 October 27, 2019 08:55

Excellent post. Keep writing such kind of information on your site. Im really impressed by it. Hello there, You've performed an excellent job. I'll certainly digg it and in my view suggest to my friends. I am sure they will be benefited from this web site.