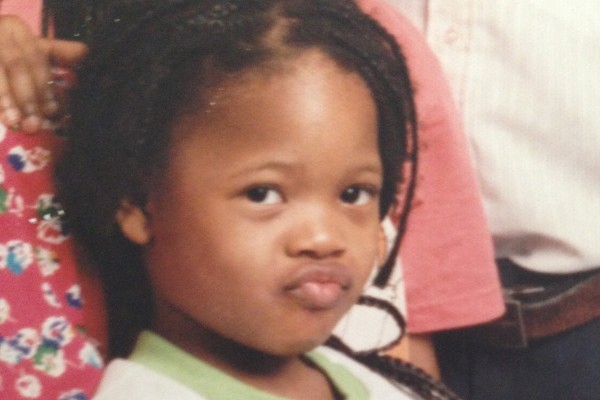

The super-adorable little girl in this photograph is the Nigerian author Chibundu Onuzo.

The Guardian posted the photo a while back when they published Onuzo’s lovely essay about her childhood experience with reading.

Don’t be fooled by the fierce cuteness of that pout and side-eye. This little girl has a reading habit that would put some of you to shame.

Onuzo’s book-loving mother inducted her into the expansive archive of story books that defined the British curricula of her own childhood. So Chibundu got to read everything from Hodgson’s Secret Garden to Lewis’ Chronicles of Narnia, in addition to American classics like Little Women and Anne of the Green Gables. As for Nancy Drew and The Famous Five series, she read those on frequent trips to a private library located about an hour away from her Lagos neighborhood.

By eleven, Onuzo was well into her European classics: The Count of Monte Cristo, David Copperfield, Jane Eyre, etc.

You’re probably asking why there aren’t any African children’s books. Why is she not reading Chike and the River? What of Drummer Boy, The Bottled Leopard, and Sugar Girl?

Onuzo recalls reading an African children’s book here and there but also noted that some of these books tended to be shoutingly ideological. “Stories of disadvantaged children, struggling to go to school against all odds, a lesson for young readers about the importance of education and listening to your parents, teachers, elders and all adults in general.” If you’ve experienced the joyless preachiness of a book like Eze Goes To School, you’d understand what she’s saying here.

Chibundu may not have cared too much for African children’s books, but African stories were a big part of her early years.

I consumed African literature in a mostly oral form. Every night my father would tell us stories that his mother had told him in his childhood, stories of the goings on in the animal kingdom, often about Tortoise but other creatures featured. The stories were told in a multimedia format. There was speech and singing and call and response. There was also a popular story-telling TV show that I watched called ‘Tale’s by Moonlight,’ whose stories gave me nightmares.

African literature came into her life much later, in her teenage years. She tells this lovely story about moving to the UK and finding Things Fall Apart in a Winchester library. There is this beautiful moment at the end of the essay when she reflects on what it means that she encounters African literature later in life.

I lost by not reading these books in my childhood. I lost by not associating the world of books and imagination with Nigeria. Like other African writers, my first novels (which I began writing from 10 years old) were set abroad, with foreign characters, with foreign names, with foreign problems. But I also gained by reading these books as a teenager…It is something to read a body of books as a teenager and realize that these are my literary parents. Children are not their parents. They can grow up to be just like them or completely different. They may look like them or they may not. They may accept them or reject them but your parents will always be your parents. Ancestry is not destiny but there is a sort of power and confidence that comes from being able to trace your lineage and draw up a family tree. I’m glad I discovered Achebe at an age when I started taking my writing seriously. It has made all the difference.

Lovely essay! It’s always inspiring to peek into a writer’s life and see those key moments and texts that shaped her relationship with literature.

What was your reading experience like?

[Read full essay HERE]

*******

Image by The Guardian]

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions