Pseudonyms are standard in the publishing world. Writers publish under names other than their legal names for all sorts of reasons—to hide their identity or simply because they don’t like their legal names.

But there are others who use pseudonyms because they believe that their message is way more important than their own individual identity. In this case, hiding a true identity ensures that readers focus more on the message than on the writer.

That was the case with Mozambican poet Jose Craveirinha. He was a prolific poet who wrote in seven different pseudonyms at different moments in his writing life: Mário Vieira, José Cravo, Jesuíno Cravo, J. Cravo, J.C., Abílio Cossa, and José G.

I encountered Craveirinha’s work a few years ago when I took an active interest in African literature written in Portuguese—or Lusophone African literature as scholars like to call it. Initially, I limited my exploration to contemporary writers such as Mia Couto and Jose Eduardo Agualusa. Blown away by the rare beauty of their work, I wanted to explore their literary ancestry and, in the process, I discovered Craveirinha’s work.

Craveirinha was born in Maputo in 1922 and came to literary prominence in the 1950s. His poetry explored everything from blackness to family bonds, even erotic love. He lived a long life and wrote for most of it.

When I came across the bit about his many pseudonyms, I was baffled. Most authors who take up pseudonyms are content with just one. Why would a writer need seven?

My sense is that pseudonyms may have been a political necessity for Craveirinha. Early on in his career as a journalist, Craveirinha struck a path of political activism. In the 1950s, he joined organizations that fought for Mozambique’s independence from Portugal, the most prominent of which was the marxist-influenced organization, FRELIMO. It’s very possible that writing under these names gave him a place of relative safety from which to engage with the oppressive colonial power.

His adoption of different pseudonyms could also have been ideologically driven. For someone who styled himself as a poet speaking on behalf of the people, a pseudonym might have been a way of distancing his personal identity from his poetry. He could impersonate the collective, speak with their voice and in their place when he was not speaking as himself but through a different persona.

Craveirinha’s collection of poems is expansive. It includes everything from racial nationalism (negritude) to revolutionary poetry, to love poems addressed to his wife to erotic verses. Maybe the pseudonyms gave him the freedom to explore a wide range of themes and styles. Perhaps these names were a little more than pseudonyms. Perhaps they were alter egos. They allowed him the possibility of inhabiting a different poetic self in order to produce different kinds of writings.

Craveirinha is one of the unsung pioneers of African literature. It is truly sad that writers like himself are relatively unknown across the continent and globally. Craveirinha was the contemporary of Achebe, Soyinka, Gordimer, Ngugi, and others. But because the global literary landscape has always been dominated by African writing in English, writers like Craveirinha remain obscure oven though they helped shape African literature as a global form.

Craveirinha achieved literary greatness in his lifetime. He wrote poetry all through his life. In 1991, he became the first African writer to win Prémio Camões—“the highest literary accolade in the Luso-Afro-Brazilian world of Portuguese-speakers.”

Craveirinha died in 2003 in Johannesburg. He was 80 years old.

Here is a link where you can read a small collection of his work: José Craveirinha: 34 Poems by Luis R. Mitras

***********

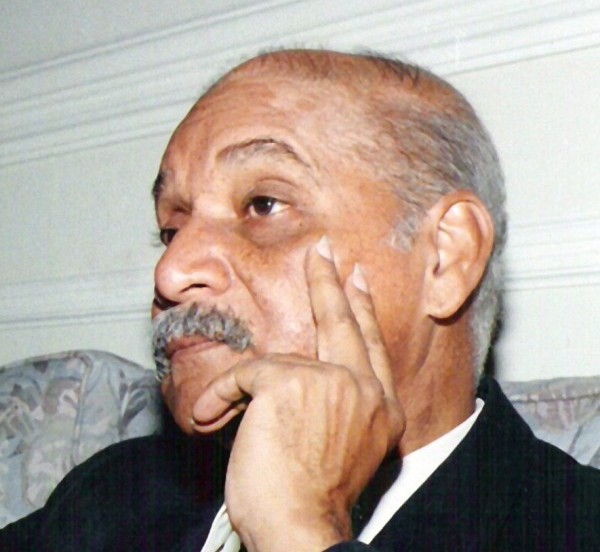

Image 1. via Tempo Cultural Delfos

Image2. by Amalviva

Image 3. by Raffi Asdourian via flickr

house alterations warkworth September 01, 2018 04:54

Everything is very open with a clear description of the issues. It was truly informative. Your site is extremely helpful. Many thanks for sharing!