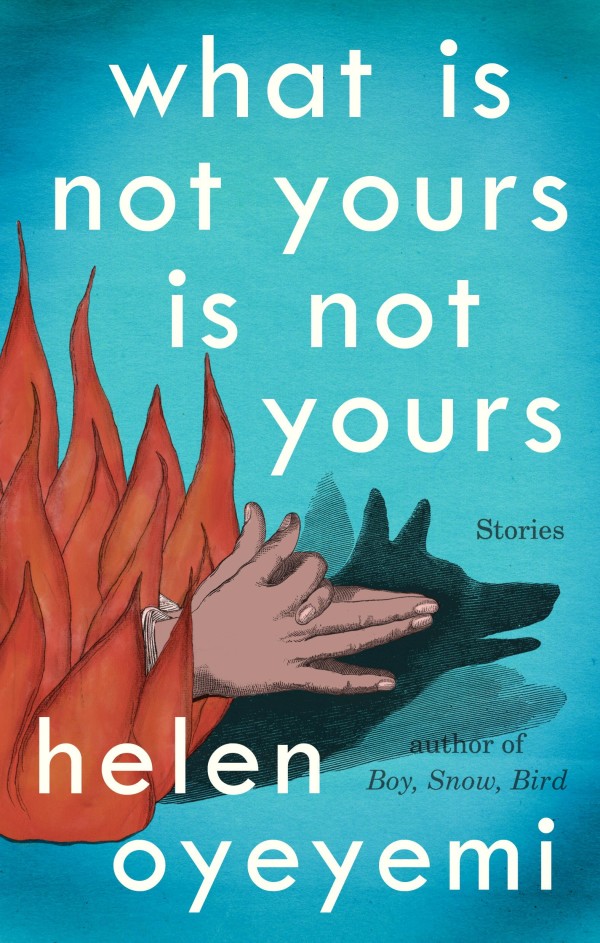

It was published a couple of weeks ago, on March 8. The reviews are gushing in and— like Helen Oyeyemi’s five other books—What is Yours is Not Yours is raking up loads of stars from happy critics.

The New York Times calls it “transcendent.” NPR says it’s “flawless.” Not surprising though. What is Yours is Not Yours is a collection of delicately woven and very readable stories featuring female characters and set in European cities. We think it is a summer blockbuster in the making.

Aaron Bady, who teaches African literature at University of Texas, Austin, is one of the most recent reviewers to weigh in on Oyeyemi’s quirky collection of stories built around the metaphors of openings, closures, and keys.

The review was published in New Republic. Enjoy these juicy bits.

In struggling to describe her work—and it is a struggle—book reviewers often praise her mastery of craft. NPR declared her new novel What is Not Yours is Not Yours “flawless,” a “masterpiece,” and The New York Times describes her as a master author who “expertly melds the everyday, the fantastic and the eternal.” But I would praise her work in almost exactly the opposite terms. Oyeyemi’s fascination is with the flaws that make us human—and the dreams through which we approach our own brokenness—and so, her stories are twisted and imperfect. As another reviewer observed, they are “idiosyncratic in a way that is hard to imagine surviving a workshop setting.” Like dreams, her books are too odd to be good, too terrible to be loved, and too broken to be masterpieces.

…

The first story Oyeyemi wrote for the collection, “books and roses,” concerns a pair of keys, a pair of lovers, a thief and an orphan, and a garden of roses and library of books. It’s a romantic, novella-length fable, filled with color and suspense, and it resolves with a striking and satisfying neatness: one key opens the door to the library, the other to the adjoining garden, and the two main characters meet in the passageway between. But “books and roses” is the only story in the book like this, and its neat resolution is more apparent than real. The most uncanny thing about the story, in fact, is the bizarreness of its narrative resolution. After you finish it—after you feel the thrill of the story’s various plots and characters snapping neatly into place—the implausible strangeness of the coincidence hangs in the air like the smell of rotting flowers. Like Chekhov’s loaded gun—in which the playwright puts a gun on stage and it waits to be fired—Oyeyemi’s keys promise a narrative resolution: when they find their lock, we expect, the story will reach its conclusion. But as in life, they seldom do.

Click here to read more.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions