My father’s voice hung in the room like fog on a harmattan morning, even long after I got off the phone with him. The more I tried to forget the issues he raised, the more his voice resonated with recurrent echo, still harsh and forthright. We had discussed a good number of familial stuffs, most of which were progressive and heart-warming. I was enjoying the moment until he asked after Amara, my younger sister.

‘She is fine, sir.’ I replied, reaching for a thick cellophane bag. I wished it could produce sounds of cars in traffic, network service jam, busy washing machine—anything that could discourage him from continuing with the call because I knew what he would say next.

‘I know she’s fine. Yes, I called her earlier. I only want to know the last time you saw her. I mean by way of visitation.’

Silence.

He began to speak again without letting me think up a defense. There was frustration and sadness in his tone.

‘I often wonder why you don’t drive across the streets to see your younger sister who lives in the same city with you.’ His voice continued to rise. ‘Are you the busiest fellow on earth?’

I almost broke into laughter. We used to mock him behind his back when we were younger because of the way he often pronounced fellow.

‘You always claim to have spoken with her on the phone, chatted with her on Whatsapp or Facebook, or seen her via Skype. Too bad!’ He spoke as though he was talking to that kid he used to spank or to the young man he often disciplined with his leather belt.

‘Why can’t you see that those useless anti-social media are the machinations of the devil to keep you separated and lonely?’

Silence.

I cleared my throat to convey my disapproval. I wished he knew how many useful contacts I had made and the amount of money that entered my bank accounts due mainly to my activities on social media. He wouldn’t listen to me. I recall that his hatred for the social media, especially Facebook, began the day my uncle’s youngest son, Ejike, uploaded the picture of his father’s dead body on Facebook. He was staying with his sick father in the hospital. Then the old man died. Ejike simply took a shot of his lifeless body the moment the doctors confirmed him dead and threw the photo onto Facebook, enthroning confusion and embarrassment.

My father listened as similar stories and more were told by our neighbors and others on a condolence visit to us. One story birthed yet another until my father learnt of a young lady who took a selfie with the dead body of her infant child and shared it a few weeks after. Though he had no way of confirming the story, that action triggered off a wild fire of hatred for the social media in my father. It continues to rage, seemingly unquenchably.

‘They only help you people trivialize humanity, trivialize diseases and death, trivialize murder and genocide, insult your elders, sow discord and promote acrimony and vengeance. Every one of you on social media is bereft of emotion. None is capable of feeling anymore!’ He roared like a distressed soldier. Not like a retired headmaster in his late sixties.

I let out the belly-bursting laughter I had struggled to stifle, yawning evasively and wishing he could stop. But he continued.

‘You were not home for Christmas because you felt you could call everyone. I tell you the truth as your father. It is not the way we were designed to be. . .’ His voice trailed off. He accusingly digressed, but I didn’t bother. I know how opinionated he could be. Everyone else in my family knows.

Silence.

‘Stop chasing shadows! You all need to change, poor souls!’ He barked as his voiced returned. Then, he ended the call.

A long monologue for one rainy Saturday morning! I thought, grinning broadly to myself.

I decided to call Amara. She didn’t pick. I lay on my back pondering over some of the issues my father just raised, wondering why he believed I only chose not to come home for Christmas because I could call and chat. I smiled and yawned until sleep carried me away.

A sharp deafening cry of pain woke me. Not even the nagging sounds of thunder or the drizzling rain could drown the cry. It pierced through my ears, wiping every trace of sleep away from my eyes. I rose and took a brisk walk out of the gate. A kid lay mangled like a potter’s clay. A car had crushed her. The driver had simply escaped. My heart was shattered. I hurried back into my room and shut the door quickly as if to prevent the spirit of death from coming in. I paced about aimlessly within the walls of the room for a while, my lachrymal gland welling up, making my eyeballs misty.

Then I returned to the scene. A crowd had gathered. Worse than the action of the killer driver, most of the people in the crowd were capturing the mangled body with their mobile devices. There was no expression of pain or loss on some of the faces.

‘What have we become?’ I bellowed in anger, taking a few steps away from them. Tears gathered in my eyes again.

‘She was the daughter of that mad woman, bro,’ a young man replied, as if I addressed the question to him. ‘She is not from this street. Her mother just abandoned her like that.’

‘A mad woman?’ I asked sarcastically, looking from his oblong head to his dirty baggy jeans.

‘Yes, her mother is mad.’ He drew closer to me, reaching for something in his hip pocket.

I waited. It was his cell-phone. He swiped the screen and made a few clicks before extending the phone to me. I took the phone from him, gaping at the piteous faces on it.

‘That’s the woman. I captured her with the little girl sometime ago and shared it on WhatsApp and Facebook.’ He spoke with an air of accomplishment.

My heart bled. I looked at him again in the face, this time not being able to see him clearly, for my eyes were pretty misty. We all knew the mad woman. Mama Tata was what children called her. She went about stark naked sometimes. Sometimes some kind women would give her something to cover over her nakedness. Then she suddenly became pregnant. It was rumored that the night watchmen were responsible. Some blamed it on policemen on night duty. Some mentioned her fellow mad folk, while some claimed it must be desperate politicians or blood money mongers. But nobody came forward to claim the child. Two years has passed since she was born.

‘Has anyone called the police?’ I asked.

‘The police?’ The young man shot me a repulsive look, shaking his head negatively.

I drew out my phone and began to dial the nearest police station. The young man called out to his friend. ‘Let’s leave here, Steve! He is calling the police!’

At the mention of police, the people began to disappear from the scene. Some shop owners around the place began to shut down. The place became almost desolate. A few moments later, the police came and cleared the body.

I went back to my room roundly troubled by that sight, even more by my father’s words. He was arguably right. The sanctity of life has become the most questionable of all creeds and the most flawed of all laws. I tried to close my eyes again, wondering where humanity is headed. My phone rang and jolted me out of those thoughts.

As I made to check the phone, my eyes caught sight of some policemen on the road outside our gate. I saw them arresting some passers-by and commuters. Knowing the nature of the police in our society, I sighed and checked the screen of my phone. Notification: Sam Agu, Bola Segun, Ahmed Ibrahim and 99 others liked a post you are mentioned in.

I went straight to my timeline on Facebook. The mangled bloody body of the mad woman’s daughter stared into my eyes. Aja, my neighbor tagged me. I quietly blocked him and unfriended all his friends.

********

Post image by Barney Moss via Flickr

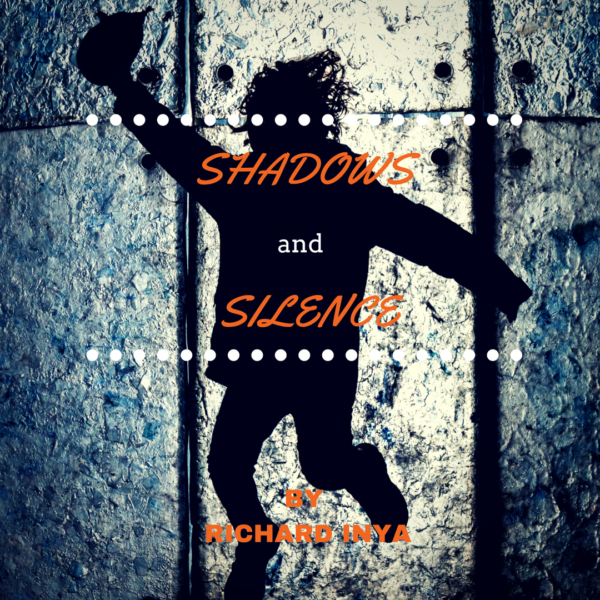

About the Author:

Richard Inya is a Nigerian poet and short story writer. His stories have featured in Ake Review, ANA Review, Praxisonlinemagazine, etc. His works have been adopted for use in their school systems by over eight states in Nigeria. He is a staff of Federal University, Ndufu-Alike, Ikwo in Ebonyi State, Nigeria. He writes and writes and writes.

Richard Inya is a Nigerian poet and short story writer. His stories have featured in Ake Review, ANA Review, Praxisonlinemagazine, etc. His works have been adopted for use in their school systems by over eight states in Nigeria. He is a staff of Federal University, Ndufu-Alike, Ikwo in Ebonyi State, Nigeria. He writes and writes and writes.

Dr Uche Nnyagu October 08, 2016 04:40

That is a wonderful piece that succinctly X-rays the happenings in our contemporary society