Before I officially moved to Lagos I was quite certain that prettiness was not a question of when but where. It was neither a question of properly blending the different layers of my contour with the perfect highlighter, nor the length of my lashes. Rather it was dependent upon who was doing the seeing – I had evidence to this of course.

When I arrive in Kwara state to spend one year at Adesoye College Offa (ACO), in the few seconds it takes to drive through the gates, sepia tinged dust creates a Cinderella-esque entrance to a 200-acre compound, which declares me definitively a ‘babe.’ Before then, in New Jersey, Pennsylvania and New York, my physical appeal is never quite the topic of conversation — or at least not in a way that I can understand. There, when I am pretty in the sea of white faces it comes with conditions. It is “for a black girl” whose “ass and boobs have developed early because she is black,” — Allison’s mother’s explanation for why she has no use for a training bra just yet. She and I will develop differently, her mother assures her. There my pretty is dependent on the layers that make me visible –— the 14-inch micro ropes that are attached to my scalp through the intricate coiling motion, that too often elicits a groan as the loop forms a knot that conjoins the human 16-inch 1B hair with my own seven-and-a-half inch mane.

But at ACO my classmates share one day in the laundry room, in between the showers and the hanging lines, as we iron our blue checkered house dresses with Sisqo’s Unleash the Dragon (our informal album of the year) playing loudly in the background, that even though I ‘form shy’, the boys in the class have ranked me as the finest girl in our set (this is with a buzz cut, by way of the school policy). “It’s not just your face,” my friend says. During an inter-house sports race where I compete in the breaststroke against my sister (she for yellow house, and I for pink), one of the seniors in red house (him 16 and me 11) comments to another senior that I have a ‘perfect hour glass shape’ — he is curious for my name.

In the year marking the new millennium, ACO, among other things, enlightens me to understand that my prettiness is out of my control. I leave ACO with a clear impression — I am pretty in Nigeria, and not quite in New Jersey, where the beholding eyes can’t see past my skin coat.

***

There are over one hundred million posts tagged #pretty on Instagram. Most of them showcase the #flawless movement that has consumed both women and men, validating and on occasion complicating the various ways we define pretty. A few weeks ago while browsing, I come across an image from @naijabestmua. It shows one side of her face, beat to purple perfection and the other half completely bare. She shares a note, “Beautiful before and after. Discoloration, dark spots, dark circles and all, but I still love me and am very much comfortable in my own skin…you should too!” Noted. I see another image that talks pretty too. It’s one of those visuals that try to captivate the viewer by framing a meaningful quote with an auspicious multicolored sky in the background. It reads, “I am pretty, but I am not beautiful. I sin but I am not the devil. I am good but I am not an angel.” I do not know about this distinction between beautiful and pretty – the supposed classification that defines

Beauty as what is within and pretty as the surface level compliment, “Yes she was the pretty girl in black that came in with Bolaji.” I’m not sure that is what I mean when I call someone pretty or beautiful, although I do use beautiful for emphasis. Amidst these hundred some million posts of #pretty I cannot overstate how much it matters that in the sea of faces I see black and brown silhouettes sometimes conventionally #onfleek, but often a redefinition of #flawless and its malleability.

I wouldn’t say I’m very good at Instagram or have the strong selfie game that so many before me have mastered. I rarely pose for said selfies because my angles have absolutely no memory. But when I do pose, I find myself looking for pretty while desperately trying to escape from it, and this little game has made tired of looking at my face. After all, I see it all the time. When I wake in the morning, in the mirror in front of my bed, then again by the entrance to my bedroom, in the bathroom, by the door on my way out. Again when I get in the car and open my social apps; with my face smizing back at me in the profile photo on my Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, WhatsApp and Peach. Sometimes when I look at my picture I think, “Is that me?” And while scrolling through those selfies where I attempt to find my pretty and put it on display, that very pretty is often disfigured as I ask myself, “who is that?”

When looking at the black and brown sea of faces framed with long weaves, perfectly fluffed tresses and contouring game akin to KylieJenner/KimKW I find myself stuck on pretty, searching for the times when pretty feels like something I can hold and feel – those times when I am in sight.

***

Now in Lagos, I am convinced that these questions of when and where to find pretty can be found, quite easily. In Lagos women show me that when the face is beat, no one can convince you that you are not pretty. For a fee of 10,000 Naira (sometimes beyond 50) on Wedding Saturdays we can all be flawless.

At first I try to find pretty on Wedding Saturdays too, not immune to the beauty bug. The first wedding I attend in Lagos, I tag along with a friend to his cousin’s special day. It is short notice, so I grab one of the few formal dresses I bring with me when I make the somewhat impromptu move from Brooklyn. The dress is black, pleated, and almost fancy so it will have to do. When we arrive at the venue and walk into the tented reception hall, the room is a vision of the chosen wedding colors — pink and green. I am the guest who dressed for the funeral in New York while avoiding the dance floor at a wedding in Ikeja GRA. A couple months later I am convinced to attend another wedding — a friend’s sister. This time I have a few weeks to prepare so I search for the perfect guest attire that says I tried, but not too much — I settle on a sleeveless slate grey wrap dress that I plan to wear with a statement grey- jeweled necklace and off white pumps. When the morning of finally arrives, there is no electricity, which induces streams of sweat I resent for interrupting my preparations. After I cool down a bit, I spend some time on my makeup eager to blend in a bit more this time around. I reach for my dress hanging in front of the armoire and bring my hands through the sleeves carefully pulling it down over my shoulders. But while I do so, my dress takes half of my makeup with it. My previously almost, nearly #onfleek face is now smeared on the bottom of my dress, but I have little time to find another outfit so I grab a big clutch that I’m sure

will hide the mixed brown magenta stain, if I commit to hold it in front of me the entire evening. “What happened to your dress?” my friend asks once I arrive at the hall.

Then at a friend’s wedding a few weeks ago I am sitting in the car with a fellow bridesmaid on the way to the ceremony. She is upset with the makeup artist’s unpolished craft visible in the already cracked foundation on her face, also two shades too light. I am fanning my face, which carries layers and layers of makeup through which I feel the exact opposite of #onfleek. I look like a clown, I am sure but I do not wipe the makeup away even though I am itching too because it is not my day (I’ve learned this is the best strategy for being a bridesmaid on Wedding Saturdays). The other bridesmaid is still venting about her makeup when she shows me an image on her phone from another wedding a few weeks earlier, “Can’t you see how much prettier this was? Can you see the difference?” she asks. I can’t really but nod my head in agreement while trying to keep still so I do not start sweating profusely all over again – this is makeup induced stress that we share so we can be allies in our misery this Saturday afternoon.

***

I have come to a conclusion from Wedding Saturdays and every other day I spend in Lagos, whether physically or digitally, browsing through my Instagram feed. Nigerian woman have either made pretty shallow and accessible, illuminating its transience or the exact opposite. We own pretty – we hold it, share it, use it, blend it, blot it, and then remove it with gentle but firm strokes of ultra gentle cleansing wipes mixed with a few drops of coconut oil. The layers come on, and then off, and then on again. But sometimes when we hold pretty like this, those layers fold into pretty and become pretty itself rather than an extension of pretty – the depths of its colors, the warmth of its tones.

And of course there is nothing wrong with wanting to feel pretty or wearing tons and tons of makeup. Yet I also want to ask – are we okay? Are we good and sane? When I first move to Lagos, I think there is something nice about always being able to be seen as pretty in a place. But even though pretty is here for everyone’s taking, there are so many caveats.

Can I only hold pretty, if I take a selfie where I find ‘my light’, if my edges are laid like baby hairs – or if the ropes hanging from my head are the right kind of heavy and long? My body is disposed to flinch the first few days when my scalp aches from Senegalese or Havanna twists; those ropes of varying weights that hang from my scalp seem to cause quite the stir here as well. Everyone I encounter is delighted to share, “your hair looks really good! You look pretty,’ delivered with a bright smile of course. Or that time a colleague sounds particularly convinced while she exclaims, “Your braids are a good look!” lending approval for my appearance now pretty, but the day before – what exactly?

These images that talk pretty either through the stroke of the foundation brush in the reflection gazing back at me in the mirror, or while my thumb swipes left, right, forward and back are inescapable. And pretty’s silhouette seems so rigid at times – stiff and unyielding to my beck and call.

***

I do not take compliments well. I get a little angry, I think, simply because I do not want to need them. But of course I do. I want to capture in a mason jar that firefly buzz in my lower abdomen where I can feel my heart beat from the bottom when he says ‘you are a vision.’ If I could keep that glowing reflection for whenever I need to be warmed from the inside out.

I have another period where I am fanatically obsessed with pretty. I am consumed with trying to understand why he disappeared. I buy lipstick, eye shadow and foundation – committed to finding my light, or angles so I can document the woman that I can be. I am thinking then that this is the way to show him that I am of something, like him. I can be the Nigerian woman who has the dress with matching shoe and bag for the wedding, or burial or whatever. So I buy four dresses with the appropriate accessories. I even make a note on my phone, ‘Outfits’. I detail the hair, lipstick shade, jewelry, dress, shoes and bag for each dress; I note which dress a sleek high-bun is most befitting and which will look best with a sleek and wavy blowout. They are still hanging in my closet.

***

Most days I spend a solid three minutes on my makeup. Sometime four if I apply blush and mascara. I like looking like a slightly polished version of what I look like when I wake up in the morning. The reflection feels more manageable like this. Yet Lagos demands that I am presentable at all times. No bum days. No grocery shopping in unruly hair – you might be seen and forgo the potential meet cute of the tall guy you first see at a friend’s house party. Or see your ex’s new girlfriend decked in a silk printed dress walking into the restaurant with an 18-inch shadow of silky Brazilian hair solidifying the outline of her silhouette.

By virtue of being a dark skinned woman, I have accepted that in some places people are not willing to see my pretty. And I have enjoyed that invisibility. Sometimes, I find it freeing. Then other times, I envy the confidence of a Naija babe, looking at herself in the mirror, not feeling bored of her face and thinking, “I look amazing!” (because of course, I can read her mind). I am not that confident about most things. I do not really believe that I can have anything I want, or that “I’m going to marry a man who drives a Range Rover, by force” (overheard in the front seat of a gold Kia Cerato while reversing onto Tiamiyu Savage Road, Victoria Island June 2013).

One last thought. What does a localized beauty mean now when a second flesh allows us all to share an image with appreciative eyes anywhere, somewhere? Pretty is global (truly it always was). I am sure my 12-year-old self would have appreciated this when returning to the U.S. from my year as a babe, finding herself once again hypervisible, yet invisible. But the 28-year-old me still has doubts about pretty’s global appreciation tour. We have been able to capture pretty, yes. But I thought we were trying to free it from the sleek copper case, the bunch of clip-ins of soft and perfectly coiled virgin-remy hair? Or maybe we have found the balance that @naijabestmua seems to exude? In exploring Asian American women and oppression, Mitsuye Yamada notes, “To finally recognize our own invisibility is to finally be on the path toward visibility. Invisibility is not a natural state for anyone.” So yes, we have made pretty visible, but can we still see ourselves?

***********

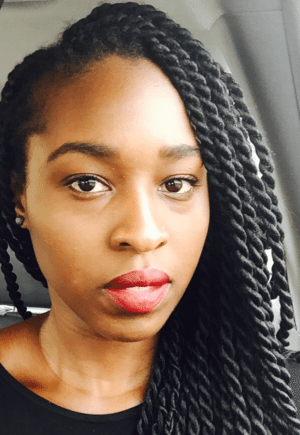

Post image by Monique Prater via Flickr.

About the Author:

Maryam Kazeem is the Managing Editor of Ventures Africa, a writer and a multimedia visual artist. Currently based in Lagos, her writing and art focus on questions of feminism, race, memory, and diaspora within Nigeria and beyond.

Maryam Kazeem is the Managing Editor of Ventures Africa, a writer and a multimedia visual artist. Currently based in Lagos, her writing and art focus on questions of feminism, race, memory, and diaspora within Nigeria and beyond.

Pretty | Maryam Kazeem | TopLeat March 27, 2017 10:11

[…] Originally published on Brittle Paper […]