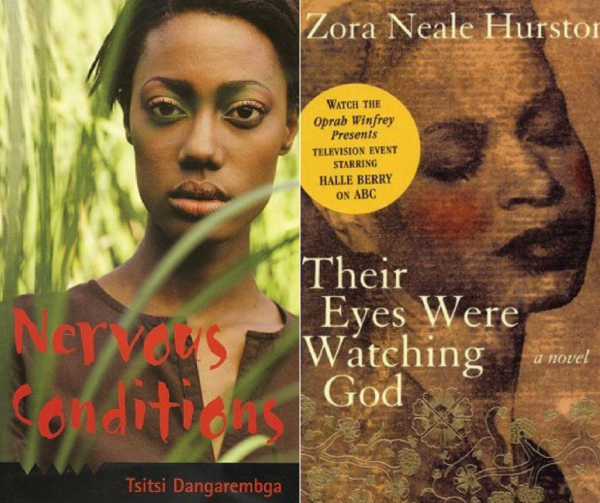

Tsitsi Dangarembga’s 1988 novel, Nervous Conditions, the story of Tambudzai, other girl-children, and women of Babamukuru’s family in 1970s British Rhodesia, begins this way:

I was not sorry when my brother died. Nor am I apologizing for my callousness, as you may define it, my lack of feeling. For it is not that at all. I feel many things these days, much more than I was able to feel in the days when I was young and my brother died, and there are reasons for this more than the mere recalling of facts as I remember them that led up to my brother’s death, the events that put me in a position to write this account. For though the event of my brother’s passing and the events of my story cannot be separated, my story is not after all about death, but about my escape and Lucia’s; about my mother’s and Maiguru’s entrapment; and about Nyasha’s rebellion—Nyasha, far-minded and isolated, my uncle’s daughter, whose rebellion may not in the end have been successful.

Tambudzai is the oldest daughter of peasants with little money to send their children to school. With the few resources available through Tambudzai’s father’s older and accomplished brother, Babamukuru, Tambudzai’s older brother is the first to benefit from the privilege of formal education. When Babamukuru and his wife are awarded scholarships for graduate studies in England, Tambudzai’s mother plants a larger vegetable garden and sells boiled eggs in the bus station to raise the money for her son’s school fees. Though five-year-old Tambudzai, as the oldest daughter, had now begun attending school, the eggs and vegetables could not be stretched to cover her school fees and were not intended to so anyway. When Tambudzai insists that she, like her brother, be permitted to continue with her schooling, her father, the least productive member of the family, rationalizes the situation with “Is that anything to worry about? Ha-a-a, it’s nothing. Can you cook books and feed them to your husband? Stay at home with your mother. Learn to cook and clean. Grow vegetables.”

Nervous Conditions is the story of how Tambudzai raises her own tuition fees by growing vegetables, and eventually excels in formal education after she replaces her brother at the Protestant mission school in town when he dies in an accident. Living with Babamukuru and his family, Tsitsi comes to know and love her highly intelligent and conscious cousin-sister, Nyasha, who has spent part of her life in England while her parents attended graduate school. Through her experience in late 1960s England, Nyasha understands the colonial relationship in a way that Tambudzai never will—Tambudzai, the daughter of peasants, who consciously and desperately does all she can to escape what she sees (while feeling great guilt) as the imbroglio of her mother’s material and intellectual reality.

The story of Nervous Conditions can largely be seen as the account of a colonized girl’s wave of strength, where toward the end of the novel, Tambudzai is one of two African girls selected to attend Sacred Heart, a multiracial convent school regarded as the best girls’ school in the country. Both Babamukuru and her father are against Tambudzai taking an opportunity so rarely made available to young black girls in British Rhodesia. It is Maiguru, Babamukuru’s wife, who convinces Babamukuru to do the right thing. Maiguru’s softly spoken words constitute a speech replete with conviction:

I don’t think that Tambudzai will be corrupted by going to that school. Don’t you remember, when we went to South Africa everybody was saying that we, the women, were loose….It wasn’t a question of associating with this race or that race at that time. People were prejudiced against educated women. Prejudiced. That’s why they said we weren’t decent. That was in the fifties. Now we are into the seventies. I am disappointed that people still believe the same things. After all this time and when we have seen nothing to say it is true. I don’t know what people mean by a loose woman—sometimes she is someone who walks the streets, sometimes she is an educated woman, sometimes she is a successful man’s daughter or she is simply beautiful. Loose or decent, I don’t know. All I know is that if our daughter Tambudzai is not a decent person now, she never will be, no matter where she goes to school. And if she is decent, then this convent should not change her. As for money, you have said yourself that she has a full scholarship. It is possible that you have other reasons why she should not go there, Babawa Chido, but these—the question of decency and the question of money—are the ones I have heard and so these are the ones I have talked of (Dangarembga: 1988, 180-181).

At the end of the book, Tambudzai returns to Babamukuru’s home in the mission after her first year at Sacred Heart and finds her cousin-sister, Nyasha, in a nervous condition quite apart from the anxious condition lived by Tambudzai as a peasant girl studying with wealthy white students in the multiracial Sacred Heart. Nyasha’s fall from a critical rage against colonial structures into madness arising from the contradictions of these structures is the beginning of a wave of struggle which is fully developed in The Book of Not, Dangarembga’s 2006 sequel to Nervous Conditions.

In The Book of Not, Tambudzai endeavors to become the educated, independent woman who can contribute to society beyond supporting a husband and family within the social and physical confines of the rural homestead or urban compound. While Tambudzai throws every last bit of herself into her studies, the fight for national independence takes full shape and tensions between white and black students at Sacred Heart deepen in a low-intensity conflict. As Netsai, one of Tambudzai’s younger sisters, and other liberation fighters gain grip of the country known to the world as Zimbabwe from 1980 onward, Tambudzai fails to rise as a young lady of Sacred Heart. She fails not because of a lack of effort or superior performance, but because of various forms of racial discrimination woven into the high ideals of the multiracial Sacred Heart, combined with the differential treatment meted out to young black ladies of Sacred Heart as the war of liberation intensifies.

At the end of the story, in the now independent Zimbabwe, Tambudzai leaves what she describes as her lowly position of copywriter in an advertising agency where her white former classmate has reached the Director level, and a white male colleague is given credit for her innovation in an advertising campaign which turns out to be a major success. Tambudzai becomes the spoilt woman both her educated uncle, Babamukuru, and her uneducated mother had anticipated—though “spoilt” structurally rather than morally. The reader closes The Book of Not with a sense of rage that the world must change and we must change ourselves simultaneously if the contributions and abilities of all individuals are to be adequately and justly recognized and rewarded.

In a similar literary spirit, Zora Neale Hurston’s 1937 novel, Their Eyes Were Watching God, is the journey to personal liberation of Janie Crawford, an African American woman of West Florida in the first half of the twentieth century. In this journey there is one arranged marriage to a man twice her age, another marriage which begins when Janie elects to walk away from her front porch with a young black man aspiring to create a town for black people, and yet another relationship through which Janie finally flourishes. The long haired, light skinned Janie is both fortunate and not-so-fortunate in her beauty. Because of her beauty, her first husband accepts her as a wife even though her grandma and guardian is not wealthy. Because of her beauty, her second husband offers to sweep her away, but once they become established in the new black town he creates, the attention captured by her beauty turns her beauty into a source of resentment for her all-powerful husband. To the last day of his life he mistreats Janie as his own insecurities bring him to equate her beauty with inaptitude and betrayal.

Their Eyes Were Watching God begins with the older Janie telling her story. Zora Neale Hurston writes:

Janie saw her life like a great tree in leaf with the things suffered, things enjoyed, things done and undone. Dawn and doom was in the branches. (Hurston: 1937, 8).

Much later we read Janie’s conclusion of sorts:

Two things everybody’s got tuh do fuh theyselves. They got tuh go tuh God, and they got tuh find out about livin’ fuh theyselves.

The relationship between Janie and her young and confident lover Tea Cake, which begins after the death of her second husband, is the moment of self actualization, joy, and freedom in Janie’s journey. Her oneness with God is the vehicle through which she sustains herself through deep hardships—including the killing of Tea Cake, which takes place at her own hands after Tea Cake contracts rabies during a hurricane and flood of epic Southern USA proportions. Beyond his own desire and control, Tea Cake becomes violent with himself and the woman he loves. When Tea Cake points a pistol at Janie, she picks up a rifle and her bullet reaches target as his teeth clench into her forearm.

Dangarembga and Hurston bring their characters to life throughout their novels and express, by the end of the stories, truths about the greater whole of existence. The art of Dangarembga and Hurston in these novels reflects the meaning of Rumi’s words in the poem, “Clothes Abandoned on the Shore”:

…in this sea there are many bright veins

and some that are dark.

The heart receives its light

from those bright veins.If you lift your wing

I can show them to you.

You are hidden like the blood within,

and you are shy if I touch.Those same veins sing a melancholy tune

in the sweet-stringed lute,

music from a shoreless sea

whose waves roar out of infinity.

In exposing the cages of social existence and waves of perseverance beneath the wings of their characters, and in turn, their readers, Dangarembga and Hurston give us the music of the shoreless sea which is the essence of progressive literature. Their work empowers without simplifying, inculcating values of freedom, courage, and critical thinking by enacting rather than pulpiteering.

Through the stories of Tambudzai, Nyasha, Netsai, Maiguru, Janie and Tea Cake, readers are offered a means to rethink their own struggles and good fortune within larger socio-political, historical contexts. Dangarembga and Hurston thus arm their readers with the knowledge that the world is harsh but not unlivable, that the world must be changed and that we can liberate ourselves in the process—including through the pain of great hardship and grave injustice.

*************

About the Author:

Salimah Valiani is a poet, activist and researcher. She has published three collections of poetry: breathing for breadth (TSAR, 2005), Letter Out: Letter In (Inanna, 2009) and land of the sky (Inanna, 2016). She reads fiction as voraciously as her young child allows and dabbles in fiction-writing. When she grows up, she aspires to writing the novel for which she has been collecting notes since 2006.

Salimah Valiani is a poet, activist and researcher. She has published three collections of poetry: breathing for breadth (TSAR, 2005), Letter Out: Letter In (Inanna, 2009) and land of the sky (Inanna, 2016). She reads fiction as voraciously as her young child allows and dabbles in fiction-writing. When she grows up, she aspires to writing the novel for which she has been collecting notes since 2006.

Salimah Valiani February 20, 2017 12:47

Can't wait to hear you and meet you on March 10 in Jozi Sis Tsitsi. You are an inspiration!