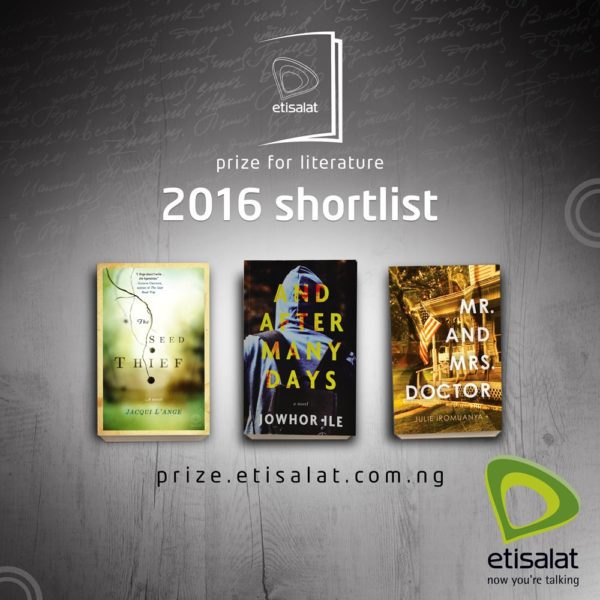

On May 20, the winner of the Etisalat Prize for Literature—awarded to a first-time African fiction book author—will be announced. Which of the three shortlisted novels is worthy of the prize? All of them! But if your soul is ailing, there is a novel here to comfort you.

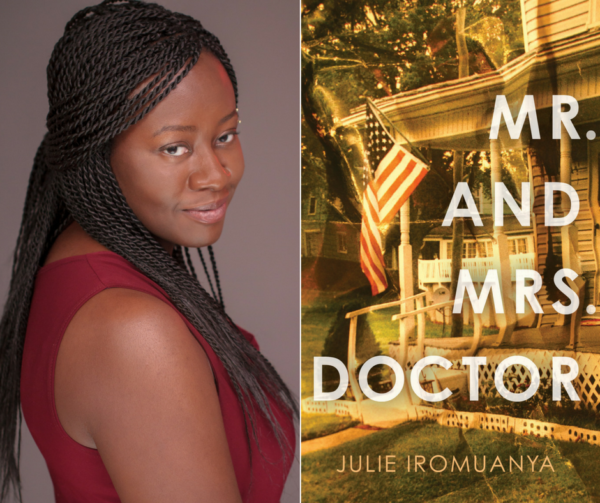

Ailment: Hubris.

Physician: Julie Iromuanya.

Prescription: Mr. and Mrs. Doctor.

First dose: “Everything Job Ogbonnaya knew about sex he learned from American pornography.”

Years ago, Job traveled from Nigeria to the United States to study medicine. His family sacrificed, and they’re proud of their doctor. But one thing: He’s not a doctor. He flunked out of college and now works as a nurse’s aid, cleaning up after an incontinent elderly man. But he can’t admit the truth to his family; he can barely admit it to himself. He agrees to an arranged marriage and brings Ifi to the United States, still trying to maintain the pretense.

This book will make you groan, cringe, and shudder as Job goes to increasingly precarious lengths to prove to himself and to everyone around him that he is “capable,” that he is a “man after all,” that he “could do anything. It was only a matter of his desire at the moment. Anything, he said to himself. If he wanted to, he could buy “a television set with one thousand channels.” At the same time, Ifi is drawn into the game, using lifestyle magazines as inspiration for her letters home: In her missives, their ratty apartment is a luxury home: “Fat red roses fill my garden. In fact, my yard alone is larger than your entire street.” Surely this can’t last. Surely.

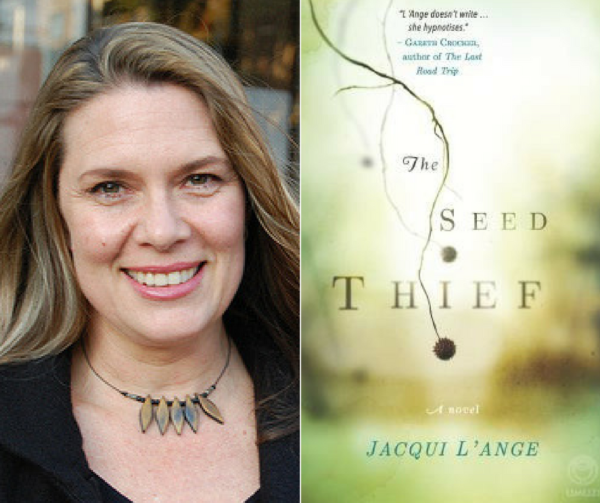

Ailment: Disconnectedness.

Physician: Jacque L’Ange.

Prescription: The Seed Thief.

First dose: “A girl on a boat on a river.”

Magdalena is a botanist on a mission. She leaves Cape Town, South Africa, for Salvador, Brazil, in order “to infiltrate a religious sect and find some seeds.” Specifically, she needs to track down the seeds of a tree that has gone extinct in its native Africa but supposedly survives in Brazil, protected by the pratictioners of Candomblé, a religious tradition that merges beliefs from Africa and the Americas. But Maddy is running from herself and her life of wandering disconnection even as she penetrates deeper into the lush gardens of the Candomblé temple. L’Ange’s novel is richly researched and full of gorgeous, sensuously characterized vegetation: “Such a lascivious little seed! On screen it would be played by a bombshell wearing a fluffy boa and feathered mules; the Marilyn Monroe of seeds, as drawn by Dr. Seuss.” You’ll find yourself drawn in and possessed by this tale, just as characters are possessed by the local deities. You’ll be charmed by the excerpts of Elizabeth Bishop’s poetry. You may have lost yourself, or you may be a lost traveler, amidst crowds of other travelers but without connection, for “they’re all podcastaways, adrift on syncretic atolls, connected to their portable MP3 tribes.” Follow Maddy as she seeks to find her way home, and perhaps you’ll find yours.

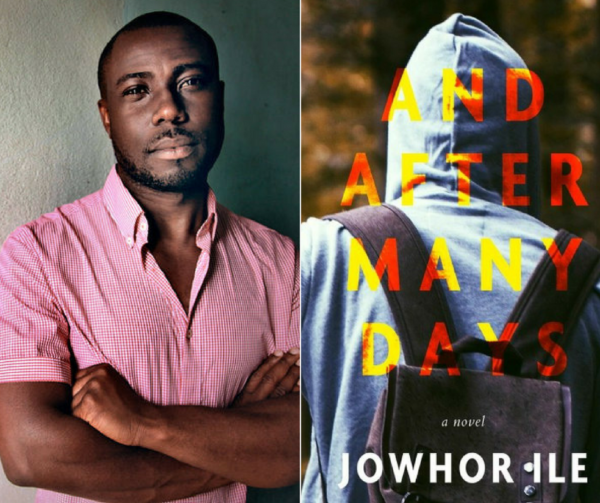

Ailment: Impatience.

Physician: Jowhor Ile.

Prescription: And After Many Days.

First dose: “Paul turned away from the window and said he needed to go out at once to the next compound to see his friend.”

Paul Utu, the eldest of three children of a Nigerian family, has gone missing. His younger brother, Ajie, fills almost the entirety of the novel with his reminiscences: watching Mexican telenovelas with his aunt and uncle, bickering with siblings, suffering through boarding school, and observing power struggles in a rural village of interest to an international oil company. Sounds boring? Not at all. Ile’s debut is leisurely and thoughtful but never boring, exploring themes of family, education, economic development, and loyalty. Ajie’s father will teach you patience with those who annoy you: “Remember what we agreed you should do when someone tries to annoy you. The backward count always works. Take it slowly from 100, and before you know it, you will think of something better than to lash out.” Jowhor Ile will teach you patience and pleasure in this fine novel.

Here’s the secret about African literature as medicine. There’s no way to overdose! So no matter your malady, try all three of these drugs. We’ll be looking forward to the next cure from each of these authors.

**************

About the Author:

David Evans reads prolifically and loves writing about what he’s read. He is working his way through books by authors from every country across the African continent. Three of his favorites are Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s Wizard of the Crow, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Half of a Yellow Sun, and A. Igoni Barrett’s Blackass.

David Evans reads prolifically and loves writing about what he’s read. He is working his way through books by authors from every country across the African continent. Three of his favorites are Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s Wizard of the Crow, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Half of a Yellow Sun, and A. Igoni Barrett’s Blackass.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions