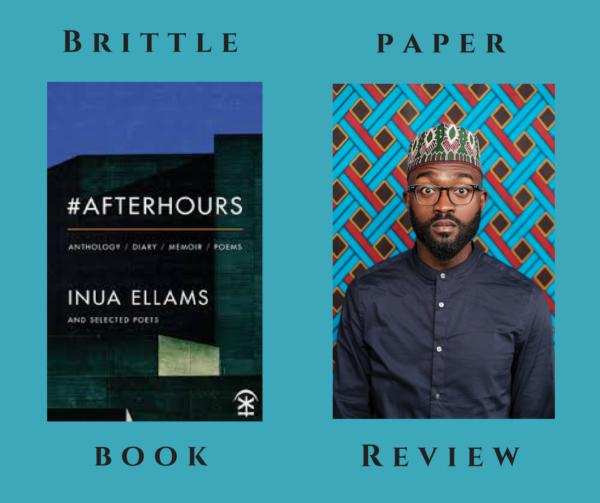

In his new anthology-cum-diary-cum-memoir, #Afterhours, Nigerian poet Inua Ellams features a collection of poems written in-response to a well-considered selection of British and Irish poems (and poets) published between 1984, the year the author was born, and 2002, the year he turned 18.

Having lived in the UK and Ireland from his teen years Ellams decided to rewrite these poems through his “Muslim-Christian-Nigerian-English-Irish-Immigrant-Golden-age-of-hip-hop” lens with a poem dedicated to each of his 18 years of childhood.

The book is a product of Ellams’s year-long tenure as poet in residence at the National Poetry Library at London’s Southbank Centre beginning in 2014, the year he turned 30 and “approaching the ‘noonlight’” of his years. As such, #Afterhours also represents a body of work that “frames” the author’s youth.

We are led through Ellams’s childhood and adolescence with stories from his life and memories from Nigeria, an extended stop in London, a stretch in Ireland and then finally returning back to London through poetry and diary entires. Ellams gives us tales from a Nigerian boarding school, a ram killing at Eid and a tribute to the activist Ken Saro-Wiwa flowing into passages that describe flights over the Mediterranean sea, a phone call received in Dublin and, at last, a long walk through the streets of London.

In one of the early diary entries, before the first poem, Ellams introduces the Welsh word hiraeth, meaning a feeling of homesickness for a home that may never be returned to, an unreachable place fuelled by nostalgia. That idea sets the tone for what he – and the writer/musician Musa Okwonga – later in the book identifies as themes of identity, displacement and destiny. It is a holy trinity of sorts, and the cornerstone upon which Ellams’s work is built. Leading on from this, I’d add place to displacement – both temporal and ethereal – as a running thread throughout Ellams’s pieces.

In the tender “Writ in Water & Blood” we meet five-year-old Ellams, who is discovering a change in life with a new baby sister. In the last stanza, Ellams flips the poem on itself, recapturing lines in a different order and giving them, collectively, a new meaning. The effect of this is arresting, and my thoughts go to his twin sister. Perhaps this is her voice – like his, but different – as the two of them come to understand themselves and their parents in relation to the new child and new identities. He ends the poem where it first began: “We find her across from our bedroom: another.”

Throughout the collection, from one scene to the next, Ellams painstakingly, and respectfully, draws parallels between regions and lives that appear to be miles apart. He demonstrates this in “No Return 1984”, his first poem in the collection written in the voices of his parents, in the year of his and his twin sister’s birth. It reads somewhere between a plea and declaration by his parents to keep the lives of their children, fearing that they are Ogbanje or Abiku children, spirit children, those who belong to the spirit world and thus destined to return there:

We feel them watching you: the contortionists, jesters,

masquerades, egunguns, other spirit brethren, guitar-

mouthed spectres, teeth of silver strings, broomsticks

for eyes, glowing coal for noses, hooves of wild horses.

We will stand night-watch until they have departed.

Ellams’s #After follows Scottish poet Iain Crichton Smith’s “No Return”, the corresponding stanza being:

The witches wizards harlequins jesters

have packed up their furniture and guitars.

The witches have gone home on their broomsticks

and the conjuror with their small horses

and tiny carts have departed.

The choice of Crichton Smith’s “No Return” and Ellams’s response to it remind us of the presence of and belief in the supernatural and spirit worlds from cultures across the globe.

He brings together regions in “An English Dream” with:

“– when Jack’s call shattered it / and whatever it is inside felt like a small continent / widening out from humanity’s west-European plains to / west-African valleys, to the backyards of my childhood / and there, friends whispering ‘bet he won’t remember us’.

Ellams’s poetry rings of lyrical prose, a conversational style of writing that is highlighted in the diary entries in the book, which is essentially what the book is, a conversation between poets. It’s no wonder then that Ellams is also a performer, one at ease in engaging his audience.

The tongue-in-cheek “Before the Immigration Tribunal” brings to mind his cleverly funny and warm ‘An Evening With an Immigrant’ performance, which was last staged in 2016. From the poem:

They asked why we came here. We replied

to master the meticulous small talk of weather,

sharpen instincts of forming ordered queues,

consume bland food, buckets of foreign beer,

chant football slogans at quiet commuters

and await good news from northern Nigeria.

Before Ellams reaches his last poem, he tells of the tragic suicide of his friend Steven and writes an homage to him. Delicately describing anguish, he writes:

There were moments before when he held my gaze

in fits of soaring laughter

while houses, whole ghost towns of lonely

glowed heavy in him.

And then:

I’ve begun to see the entire

network of a hollow city in his chest.

After a blitz of emotions and by the time I get to the last poem, “The Aftermath 2002”, I am struck.

It starts with the verse: “I feel like an exiled child going walkabout by night / for the first time…”

With its simplicity we are thrown back to the beginning of the collection, an infant entering a new world, the world as we know it in “No Return 1984”. Or indeed the middle, entering the teen years where the infant is now an adolescent and has to navigate once more a different world, one where classrooms full of children with heritage from several continents are adverts for multiculturalism but insults like being called a “nigger”, as the poet describes, are not far away.

The poem reads like an ode to the city of London. With Ellams, we see Mrs Adeyemi with her trolley filled with yams and plantain, and faded ankara atop her head. We sidestep belt buckles, razors and used condoms. We pass by imposing shiny buildings towards open grey carparks – steely, loud, fast, concrete and cold, a beautiful bleakness.

I’m sitting in a small coastal town, across time zones, thousands of miles from that place. But the sounds and vibrations of “the stupendously huge passing / of fire trucks and sirens” along London roads thunder through my chest. Reading the poem, I inexplicably well up. I follow Ellams as he meanders through the city, and I get a longing that hurts. It’s a hurt that I want to feel, like pressing a bruise on one’s thigh or a sore on the tongue, checking that the wound is still there. I’m reminded that it is.

On one of the opening pages, in his signing of the book, Ellams wrote that he hoped I’d find something of myself within the pages. As I finish the last poem, I’m reminded of hiraeth and at once uncertainties of my own that I’d repeatedly and dismissively batted away now come to the fore, looking for an answer.

********

Buy #Afterhours HERE.

*********

About the Author:

Billie McTernan is a writer and editor covering cultural and political affairs across Africa. She is a keen traveller but hates packing. You can find her on twitter @billie_mack

Billie McTernan is a writer and editor covering cultural and political affairs across Africa. She is a keen traveller but hates packing. You can find her on twitter @billie_mack

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions