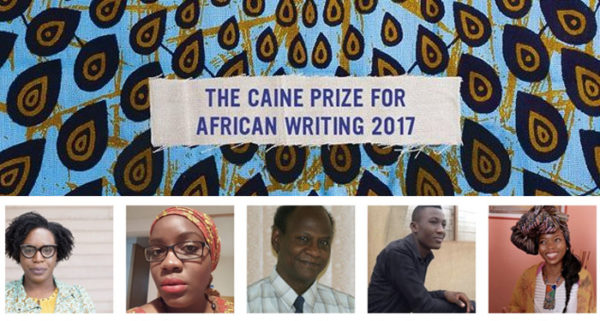

The 2017 Caine Prize shortlist, which was announced two weeks ago, is arguably, as Petina Gappah suggested, the prize’s most thematically-diverse shortlist in years. Each of the five stories—Lesley Arimah’s “Who Will Greet You at Home?”; Arinze Ifeakandu’s ‘God’s Children Are Little Broken Things”; Bushra Al-Fadil’s “The Story of the Girl Whose Birds Flew Away”; Magogodi oaMphela Makhene “The Virus”; and Chikodili Emelumadu’s ‘Bush Baby”—has something going for it.

The 2017 Caine Prize shortlist, which was announced two weeks ago, is arguably, as Petina Gappah suggested, the prize’s most thematically-diverse shortlist in years. Each of the five stories—Lesley Arimah’s “Who Will Greet You at Home?”; Arinze Ifeakandu’s ‘God’s Children Are Little Broken Things”; Bushra Al-Fadil’s “The Story of the Girl Whose Birds Flew Away”; Magogodi oaMphela Makhene “The Virus”; and Chikodili Emelumadu’s ‘Bush Baby”—has something going for it.

The judging panel comprises the 2007 Caine Prize winner, Monica Arac de Nyeko; author and Chair of the English Department at Georgetown University, Professor Ricardo Ortiz; Libyan author and human rights campaigner, Ghazi Gheblawi; University of Southampton’s African literature scholar, Dr Ranka Primorac; and the chair, Nii Ayikwei Parkes. In a brief piece on The Caine Prize Blog, titled “Finding Sweetness in the Caine,” Nii Ayikwei Parkes writes about the collective strength of the shortlist.

Here is an excerpt from his piece.

*

People who know me will know that I have been one of the Caine Prize’s critics for many years; first as an outside observer, then from the inside as a member of the Caine Prize council. My problem has never been the idea of the prize itself, but elements in its setup that I believed skewed its relevance away from the continent of Africa. The saving grace of the Prize has always been the winning writers, who have gone on to do amazing things and have continued to engage with and help develop literature on the continent.

In a world where, in the centre, aesthetics are often conflated with ideas of quality (Victor Ehikhamenor’s recent comments noting how Damien Hirst’s appropriated versions of Ife art seem to have rid them of the tag ‘primitive’ reserved for the originals, only serve to reinforce this approach), my concerns were to do with slants in the narrative. What did the Prize say of contemporary short story writing in Africa if most of the entries were published by editors in Europe and North America? As we are a continent with hundreds of languages, can a prize with no translations allowed possibly claim to reflect the continent’s voice? It is thus a huge pleasure to have read a pile of entries where the majority were published on the African continent and to have a translated story on the shortlist.

Read the full essay on the Caine Prize blog.

*

Read our #CainePrize2017 reviews of Arinze Ifeakandu’s “God’s Children Are Little Broken Things” and Chikodili Emelumadu’s “Bush Baby.”

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions