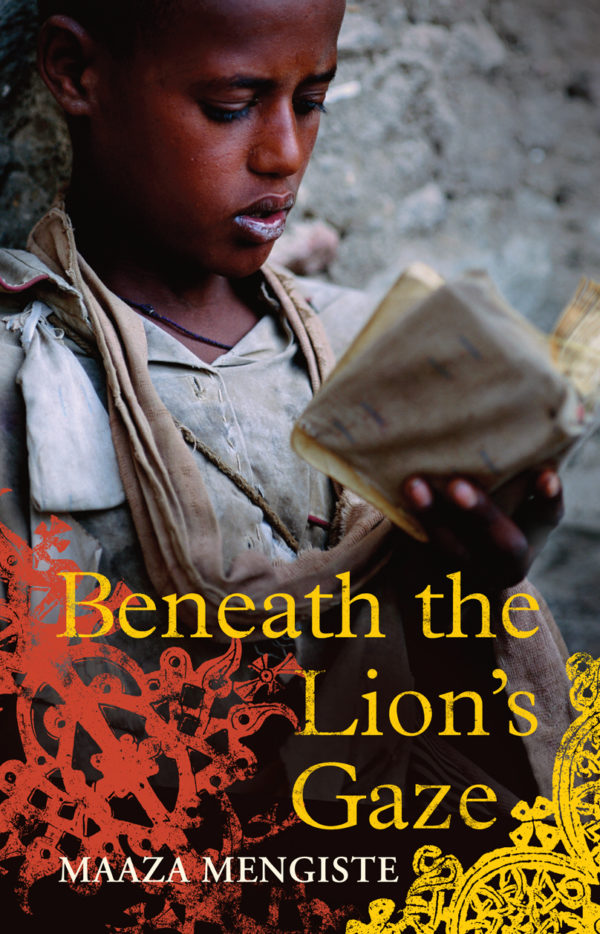

Maaza Mengiste might have just one novel published so far, in 2010, but she is one of the most visible Ethiopian writers on the international scene. That novel, Beneath the Lion’s Gaze, is an empathetic unraveling of the 1974 Ethiopian Revolution through the eyes of a father and his two sons. Here is a description from the book’s publishers, W.W. Norton & Company.

This memorable, heartbreaking story opens in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 1974, on the eve of a revolution. Yonas kneels in his mother’s prayer room, pleading to his god for an end to the violence that has wracked his family and country. His father, Hailu, a prominent doctor, has been ordered to report to jail after helping a victim of state-sanctioned torture to die. And Dawit, Hailu’s youngest son, has joined an underground resistance movement—a choice that will lead to more upheaval and bloodshed across a ravaged Ethiopia.

Beneath the Lion’s Gaze tells a gripping story of family, of the bonds of love and friendship set in a time and place that has rarely been explored in fiction. It is a story about the lengths human beings will go in pursuit of freedom and the human price of a national revolution. Emotionally gripping, poetic, and indelibly tragic, Beneath The Lion’s Gaze is a transcendent and powerful debut.

The novel was runner-up for the 2011 Dayton Literary Peace Prize, and a finalist for a Flaherty-Dunnan First Novel Prize, an NAACP Image Award, and an Indies Choice Book of the Year Award in Adult Debut. It was further named in The Guardian‘s list of the 10 Best Contemporary African Books.

With her first book’s success, expectations are naturally high for her second. But it has been seven years since and she hasn’t made an announcement.

Seven years isn’t the average gap between first and second books by top writers: Aminatta Forna had four years between The Devil That Danced on the Water (2002) and Ancestor Stones (2006); Chimamanda Adichie had three years between Purple Hibiscus (2003) and Half of a Yellow Sun (2006); Jhumpa Lahiri had three years between Interpreter of Maladies (1999) and The Namesake (2002); Zadie Smith had two years between White Teeth (2000) and The Autograph Man (2002); and Zukiswa Wanner had two years between The Madams (2006) and Behind Every Successful Man (2008).

But in the hustle that writing is, most struggle to defeat that “sophomore slump.” Sometimes, though, it isn’t because of a struggle to write again. For reasons ranging from deliberate abstinence to preoccupation with other engagements, it is usual for that gap between first and second books to stretch for as long as anything. Case in point: Petina Gappah, with her work as a lawyer, had six years between An Elegy for Easterly (2009) and The Book of Memory (2015), and then one year from that before her third book, Rotten Row (2016), with her fourth already completed. And much-discussed cases in point: Marilynne Robinson’s second novel, Gilead (2004), came twenty-four years after her first, Housekeeping (1980); and Arundhati Roy’s recently released second novel, The Ministry of Utmost Happiness, came twenty years after her first, The God of Small Things (1997). Still, in the two decades between those novels, both women were very productive with essays and nonfiction.

But unlike these examples—and even with her publishing essays since then—Maaza Mengiste’s seven-year gap since Beneath the Lion’s Gaze is due to an intriguing reason. In a recent interview with The Creative Independent, she discusses why she still isn’t ready with her second novel: She threw away the novel’s first draft and began all over.

Now that could scare an aspiring writer.

So why? Why didn’t she rework it, beat it into shape? Why did she dispense of years’ worth of labour in its entirety? Why didn’t she keep the manuscript, give it time, hope to return to it?

Her reason is simple: she wants perfection.

This second novel, which is almost completed now, is titled The Shadow King, and has taken the past six years to get right. It is “set during World War II and it’s focusing on the stories behind Mussolini’s invasion of Ethiopia.”

When the difficulties first surfaced, Mengiste was advised to simply get on with it and get it out and then focus on writing a third book, but she couldn’t.

I’ve had certain writers who are now on their third or fourth book tell me things like, “Oh, just get it done. Don’t even worry about the second book. Just get it out there. Just do it. Just get it done. Your third book is going to be the book that you’ll really like. The second one is always horrible.” I didn’t want to do that. I didn’t want to accept that.

The success of her first novel came with a pressure to do well with her second, which complicated the already tough job of merely writing it, which then led her to try to replicate the tried-and-trusted formula of Beneath the Lion’s Gaze.

I was trying to do everything that I thought I did well in the first book. I was trying to recreate that the second time around. It was a mistake. By the time I finished a draft of this second book, I looked it over and said, “This is crap. This is really bad.” It was a moment of complete discouragement.

Mengiste’s frankness is even more remarkable considering how her career is immersed in creative writing. She is a New York University MFA creative writing graduate, is currently Visiting Assistant Professor of Creative Writing at Queens College of the City University of New York, and she teaches the course in the Lewis Center for the Arts at Princeton University.

But this was her writing a second novel, trying to not repeat herself. This was her imagination being constrained by the “mountains of research” she had piled up—“fascism, reading and listening and watching Mussolini’s speeches…military maps.” It took a teasing-out of her writing sensibility during a meeting with the Croatian writer Dasa Drndic for her to find her feet again. In her book Trieste, set during the Nazi occupation of Italy in World War II, Drndic had done something Mengiste aspired to: she’d combined fictional imagination and historical research in a way that Mengiste had “never seen done before.”

We were in Italy having wine. She was smoking. I was talking to her about the troubles I was having finding the story in my new novel. I had done so much research for it, but the story was escaping me. She took a puff of her cigarette and said, “You know, that’s the trouble with all you Americans. You care too much about stories. Fuck stories. Who cares about stories? What do you want to say and how do you want to say it?” I thought back to that moment when I was sitting at my desk and I’d just come back from meeting with my editor. What do I want to say?

I thought, “If I could do anything I wanted and I’m not worried about telling a story but I’m just letting the story come out, what would I do then?” Then I threw away the whole manuscript. Tossed the entire first draft of the book. I started again from page one. It took a few days before I felt like I hadn’t been sucker punched in the gut. I just sat at the computer for a while. I kept saying, “You can do anything you want to do now. What do you want to do?” I started writing. I rejected every instinct I had to play it safe and pushed even further. Now the book is almost done and I’m really happy with the way it’s been turning out.

Born in Addis Ababa, Mengiste lived in Nigeria and Kenya before moving to the US. A Fulbright Scholar and World Literature Today’s 2013 Puterbaugh Fellow, most of her work—in The New York Times, Lettre Internationale, Granta, Callaloo—revolves around migration, the Ethiopian revolution, and the plight of sub-Saharan immigrants arriving in Europe.

We do not yet know what The Shadow King will be like, how different it would be from Beneath the Lion’s Gaze, but we do hope for it to come in that same lyrical prose as her first. But most importantly, we wish her the best of luck.

Read the full interview with Maaza Mengiste at The Creative Independent.

Otosirieze Obi-Young June 26, 2017 16:31

Thank you, Austin. We're waiting for THAT novel.