African Poetry Book Fund’s New-Generation African Poets: A Chapbook Box Set (Nne) has been featured in Vogue magazine. The feature, written by Tariro Mzezewa, who is Zimbabwean, is titled “In Times of Division, Finding Refuge—and Fighting Back—Through Art.”

It explains how poetry and the writings of black women constitute important resistance in the age of Donald Trump, how they capture the political uncertainty felt particularly by immigrants in the US following Trump’s travel ban on seven—now six—Muslim countries.

It opens with lines from Warsan Shire’s poem, “what they did yesterday afternoon,” mentions the work of Chimamanda Adichie, Imbolo Mbue and Yaa Gyasi on “some of the experiences of being an African woman in the West,” states how she “found solace in the poems written by the young ‘Afropolitans,'” a group she finds to be “the answer to Trump’s vision of America and Theresa May’s vision of Britain” because they “will not identify as any one ‘thing.'” And then she settles on the chapbook set.

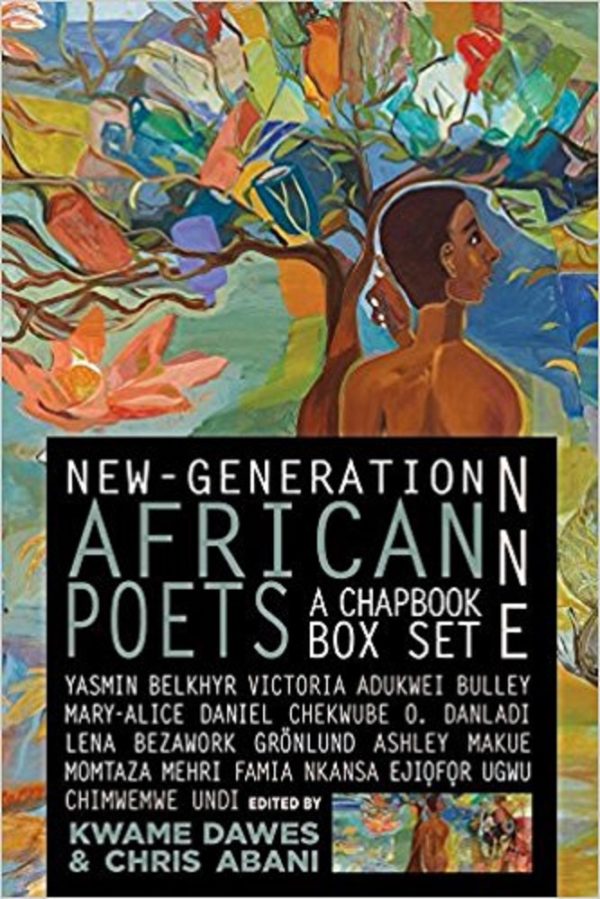

Edited by Kwame Dawes and Chris Abani, New-Generation African Poets: A Chapbook Box Set (Nne) collects chapbooks by ten poets: Yasmin Belkhyr, Victoria Adukwei Bulley, Chekwube O. Danladi, Mary-Alice Daniel, Lena Bezawork Gronlund, Ashley Makue, Momtaza Mehri, Famia Nkansa, Ejiofor Ugwu, and Chimwemwe Undi. Begun in 2014, the series “seeks to identify the best poetry written by African poets working today, and it is especially interested in featuring poets who have not yet published their first full-length book of poetry.”

Here is an excerpt from Vogue‘s feature.

*

New Generation African Poets, a 2017 anthology of the work of 10 Afropolitan poets (nine of whom are women) managed to tap into the anxiety I’d felt even before Trump took office, over many years of various detainments at airports in the United Kingdom, in Italy, and in the United States, as I once again would wait to explain that no, I wasn’t American, so I didn’t have an American passport, and no, I didn’t have any other passport, but I had the right documents to travel. They were here for me again, now that the anxiety had reached a new tenor, particularly sharp in its sense of disappointment that the world I had been raised in was somehow closing. With countries shutting borders, and with leaders from Trump to Malcolm Turnbull attempting to force people to self-identify as one or the other, these women were grappling with the difficulties of being forced to choose an identity. Afropolitans, I realized, are the answer to Trump’s vision of America and Theresa May’s vision of Britain. We will not identify as any one “thing,” as we are intrinsically so many. In that way, we are the future.

There are other ways in which these poems reflect our current moment. Nearly every part of the anthology is weighted by histories of colonization and the fight for independence. Each book in the anthology is adorned with images of dark bodies; traveling, in gardens, in the sea. Images of African bodies as angels and mermaids painted by the late Eritrean artist Ficre Ghebreyesus seem to eerily reflect the perilous daily journey made by Africans crossing the Mediterranean (“This sea has always swallowed us/ boats have always failed us/ land has always meant barbed wire,” writes Momtaza Mehri) and fleeing their own countries for safer ground, as in Lena Bezawork Gronlund’s “Everything Here.” But no poet’s work remains rooted in a time period: Rather, each poem moves through history and transitions into the present, where war and a sense of belonging remain continued struggles. The poets reach, through the most delicate prose, for something many people are still in search of: understanding.

The scariest part of living in Trump’s America is knowing that everything is random. At any moment, buffeted on by the winds of fate, or flattery, or harsh, unstudied action, he could sign an executive order that could irrevocably change my life— and that’s not something I can fight directly or alone. This anthology reminds me that poetry and all art that gives voice to women, immigrants, and people of color has a crucial place in the fight against demagoguery—and that history will remember the way that we treat the most vulnerable among us.

It’s fitting that the anthology ends with Chimweme Undi’s “The Habitual Be,” a collection about the experiences of itinerant Southern Africans, whether migrant workers or political refugees. Undi’s collection, perhaps unintentionally, ends with a reminder that despite our differences, we are connected:

Of course we come together different,

found a better way to separate this breath

from our bad habit of living, to name a

circle a circle and disregard a line.

Read the full feature HERE

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions