To mark our seventh anniversary on August 1, 2017, we announced the inaugural Brittle Paper Literary Awards, to recognize the finest, original pieces of African writing published online. The awards come in five categories: Fiction, Poetry, Nonfiction, Essays/Think Pieces, and the Anniversary Award for works published on our blog. The winners in the fiction, poetry, creative nonfiction and essays/think pieces categories will receive $200 each, while the winner of our Anniversary Award will receive $300. The winners will be announced on October 23, 2017.

The 10 Nominees for the Brittle Paper Award for Fiction

Sibongile Fisher (South Africa), for “A Door Ajar” in Short Story Day Africa: Migrations

Sibongile Fisher is a poet, writer and drama facilitator from Johannesburg, South Africa. She is the winner of the 2016 Short Story Day Africa Prize for her short story, “A Door Ajar.” She is a co-founder of The Raising Zion Foundation, an arts organisation that focuses on promoting literature, poetry and the performing arts in high schools. She holds a BCom degree in Marketing Management and a higher certificate in Performing Arts and wishes to pursue an MA in Creative Writing. Her short story, “A Sea of Secrets,” written for young adults, was published by Fundza under their mentorship program and it appears in their “it takes two!” volume 2 anthology.

Sela watched in horrified wonder as the infant lay still on the vinyl-tiled floor. Something moved inside her – a storm far off on the horizon. She looked at her mother, MmaLeru, who was cleaning her up, handling her vulva as though it were a damaged chest of useless memories.

Petina Gappah (Zimbabwe), for “A Short History of Zaka the Zulu” in The New Yorker

Petina Gappah is an international lawyer. Her debut collection of stories, An Elegy for Easterly, won The Guardian Best First Book Award in 2009 and was shortlisted for the Frank O’Connor International Short Story Award and the Los Angeles Times Art Seidenbaum Award for First Fiction. Her first novel, The Book of Memory, was longlisted for the 2016 Baileys Women’s Prize and nominated for the 2017 PEN Open Book Award and the 2016 Prix Femina etranger. Her most recent work is the story collection, Rotten Row. She was named Brittle Paper’s African Literary Person of 2016.

How could any of us have imagined, in the innocence of those days, that there had been this darkness at the school? A darkness that had led to Gumbo’s death and then, all these years later, to Nicodemus’s, and would now lead to Zaka’s own.

Arinze Ifeakandu (Nigeria), for “God’s Children Are Little Broken Things” in A Public Space

Arinze Ifeakandu was the editor of The Muse (No. 44) at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka where he studied English and literature, graduating in 2016. In 2013, he attended the Farafina Trust Creative Writing workshop and was shortlisted for the BN Poetry Prize in 2015. His short story, “God’s Children Are Little Broken Things,” won him a 2015 Emerging Writer Fellowship at A Public Space magazine, was included in Brittle Paper‘s list of the best pieces of 2016, and was a finalist for the 2017 Caine Prize.

One night it rained so hard, it sounded like pebbles hitting the roof. You shut the windows, but the wind still filtered in. You stopped reading and eased into bed beside him. You had to spoon against him because the blanket was small. Your nose was on his neck, and you whispered, Kamsi, are you awake?

Binyavanga Wainaina (Kenya), for “Ships in High Transit” in Expound

Binyavanga Wainaina is a journalist and winner of the 2002 Caine Prize for African Writing. He is the founder of Kwani? magazine. His memoir, One Day I Will Write About This Place (2011), was picked for Oprah’s Book Club. In 2014, he was included in TIME‘s “100 Most Influential People in the World.” He has taught at Williams College, Union College, and the Farafina Creative Writing Workshop, and was Director of the Chinua Achebe Centre at Bard College, U.S.A. He is the recipient of numerous honours and fellowships, including from Lannan Foundation and Africa’s Out!. He is currently a DAAD Fellow in Germany.

Matano often wonders why it is that people so often become what their faces promise. Shifty-eyed people will defy Sartre, become subject to a fate designed carelessly. How many billions of sperm inhabit gay bars, and spill on dark streets in Mombasa? How does it happen that the shifty-eyed one finds its way to an egg?

Namwali Serpell (Zambia), for “Triptych: Texas Pool Party” in Triple Canopy

Namwali Serpell‘s first published story, “Muzungu,” was selected for The Best American Short Stories 2009, shortlisted for the 2010 Caine Prize for African Writing, and anthologized in The Uncanny Reader. Her story, “The Sack,” won the 2015 Caine Prize. In 2011, she received a Rona Jaffe Foundation Writers’ Award. In 2014, she was chosen as one of the Africa 39. Her first novel, The Old Drift, is forthcoming with Hogarth Press (Penguin Random House) in 2018. An associate professor of English at UC Berkeley, her first book of literary criticism, Seven Modes of Uncertainty, was published in 2014 by Harvard University Press. Her work has appeared in The New Yorker, Tin House, Triple Canopy, The Believer, n+1, McSweeney’s Quarterly, Bidoun, Enkare Review, Cabinet, The San Francisco Chronicle, The L.A.Review of Books, Public Books, The Guardian, and in some short story anthologies.

The heat rises up, sings against the skin. Clothes fall off, swimsuits blossoming from beneath, in colors as neon and elaborate as the sunset to come. We dance and we dance. All of this beauty, all of this rolling, dipping brown flesh, like desert dunes in the shadow or desert dunes in the sun.

Megan Ross (South Africa), for “Farang” in Short Story Day Africa: Migrations

Megan Ross is a writer, poet and journalist from the Eastern Cape in South Africa. She is the 2016 Iceland Writers Retreat Alumni Award winner. She was runner-up for the National Arts Festival Short.Sharp Award and second runner-up for the 2016 Short Story Day Africa Award, with her short story, “Farang.” She has been shortlisted for the Miles Morland Writing Scholarship and longlisted for the Writivism Prize. Her writing has been featured in New Contrast, New Coin, The Kalahari Review, Aerodrome, Itch, and Prufrock. She has also written for the Mail and Guardian, Fairlady, Glamour, GQ and O, the Oprah Magazine. Her first book, a collection of poetry called Milk Fever, is forthcoming in 2018 from uHlanga.

Across the road from my childhood home is a stretch of ordinary veld. Red-hot pokers push through the thick grasses like babies’ heads, the lick and curl of the Indian Ocean only a breath away. I wish you could see it: the way the sky shines like polished silver; the gulls descending on unsuspecting shad. There is something freeing about this place, in a breathing, thinking kind of way.

Linda Musita (Kenya), for “Squad” in Enkare Review

Linda Musita is a writer and media lawyer. Lives and eats in Nairobi. Still loves the 90s. Can’t seem to find the words in third person to write about what few outdated literary achievements she has or drop big literary names she has photo-bombed. Not to say that she can’t write about other people and random things in third person, ’cause she can.

“Speaking of women, look at the gang that walked in while you were being offended by curt goodbyes.”

“The Femioso eat here?”

“Your BFF is one of them.”

“The Squeegee appointed herself. I respected her pseudo-feminist outrage until I discovered she is anti-me and anti-every-other-woman-on-blue-earth. As are all Femioso. Mean girls.”

TJ Benson (Nigeria), for “Tea” in Short Story Day Africa: Migrations

TJ Benson is a writer, photographer and quantity surveyor. His chapbook of photography, Rituals, was published online for free digital download in 2015. In 2016, he was shortlisted for the Saraba Manuscript Prize, was co-winner of the Amab-HBF Prize, and was first runner-up for the Short Story Day Africa Prize, with his story, “Tea.” He is interested in pasta, in cooking as a means of mental care, and in the ways a body breaks into stories.

She is Tiv and knows no English. He is German with familial connections to the Nazis. They are in a hotel room somewhere in Italy. On the bed is an assortment of sex toys. A gruff voice behind the camera orders them to take off their clothes. The girl doesn’t understand English, and a heavy-set woman in an orange buba gown whispers the translation into her ear. The boy places his finger on the girl’s cheek, testing the texture. She shivers at the touch.

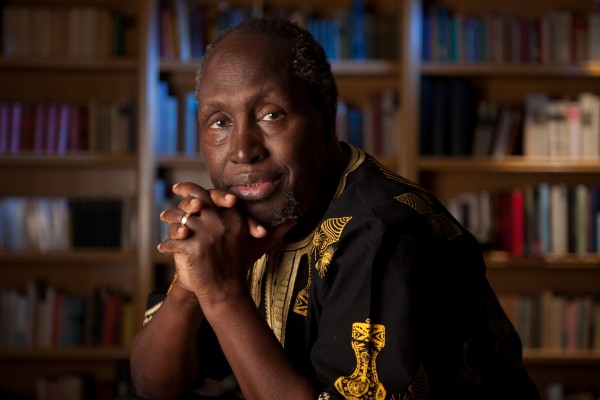

Ngugi wa Thiong’o (Kenya), for “The Upright Revolution: Or Why Humans Walk Upright” in Jalada: The Language Issue

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o is a novelist, playwright, theorist of post-colonial literature, and, at the present, Distinguished Professor of English and Comparative Literature at the University of California, Irvine, U.S.A. He is best known for his novels Weep Not, Child (1964), The River Between (1965), A Grain of Wheat (1967), Petals of Blood (1977), Caitani Mutharabaini (1981) which was translated into English as Devil on the Cross (1982), Matigari (1986), and Murogi wa Kagogo, translated into English as Wizard of the Crow (2006); as well as the play Ngaahika Ndeenda (I Will Marry When I Want), co-written with Ngugi wa Mirii, and the memoir Detained: A Writer’s Prison Diary (1982). His collections of essays include Homecoming (1972), Writers in Politics (1981, 1997), Decolonising the Mind (1986), Moving the Center (1994), and Penpoints, Gunpoints and Dreams (1998). He has edited the literary journals: Penpoint, Zuka, Mutiiri, and Ghala (guest editor for a 1964 issue). He has taught at the University of Nairobi, Makerere University, Northwestern University, Byreuth University, Yale, and New York University. He is the recipient of the 2001 Nonino International Prize for Literature and many honorary doctorates. He is also an Honorary Foreign Member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters and a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

A long time ago humans used to walk on legs and arms, just like all the other four limbed creatures. Humans were faster than hare, leopard or rhino. Legs and arms were closer than any other organs: they had similar corresponding joints: shoulders and hips; elbows and knees; ankles and wrists; feet and hands, each ending with five toes and fingers, with nails on each toe and finger.

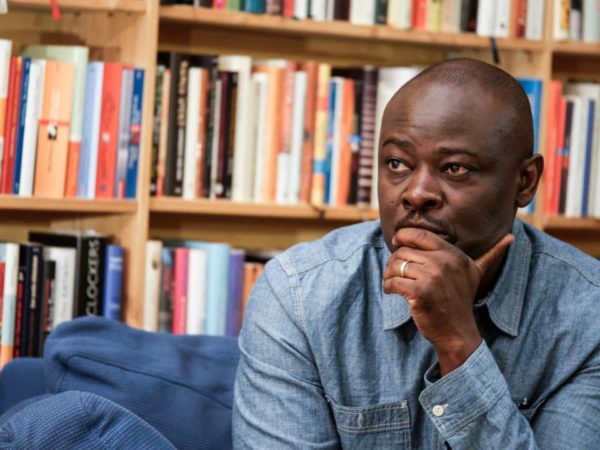

Helon Habila (Nigeria), for “Beautiful” in Adda

Helon Habila is the author of the novels: Waiting for an Angel (2002), which won the 2003 Commonwealth Writers’ Prize for Best First Book (Africa Region); Measuring Time (2007), won the 2008 Virginia Library Foundation Prize for Fiction and was nominated for the Hurston/Wright Legacy Award and the Dublin IMPAC Prize; Oil on Water (2010), which was shortlisted for the 2012 Commonwealth Writers’ Prize for Best Book (Africa Region), the 2013 PEN/Open Book Award, and the 2013 Orion Book Award. His short story, “Love Poems,” was awarded the 2001 Caine Prize. In 2015, he was a co-winner of the Windham-Campbell Prize. He was the first African Writing Fellow at the University of East Anglia, where he stayed as a Chevening Scholar, a Chinua Achebe Fellow at Bard College, New York, and a DAAD Fellow in Berlin, Germany. He has edited several anthologies including the British Council’s New Writing (2005), Dreams, Miracles and Jazz (2006), and The Granta Book of the African Short Story (2011). A board member at Africa Writers Trust, he has been a contributing editor to the Virginia Quarterly Review since 2004. From 2010 to 2013, he coordinated and facilitated the Fidelity Bank Writers Workshop in Nigeria, and edited an anthology of stories generated by the workshop participants, Dreams at Dawn (2012). In 2013, he and the publisher, Parresia Books, started a publishing company, Cordite Books, dedicated to publishing African crime and detective stories. He is presently a professor of Creative Writing at George Mason University in Fairfax, Virginia.

Then, at the very last minute, a corner kick was taken and the pitch watched in silence as the perfectly curving ball rose and dipped, the players jumped to head it into the net, and then, when it was almost outside the eighteen, a leg rose in a bicycle kick and connected with the ball, redirecting its trajectory to the back of the net. It was beautiful.

Osalam October 11, 2017 05:22

Yaa is the best