Author Kazuo Ishiguro’s novels have explored everything from post-war Japan (An Artist of the Floating World), to landed gentry (Remains of the Day), to a dystopian near-future (Never Let Me Go). The sheer beauty of these works has led to their adaptation to film, and inspired entire franchises such as Downton Abbey. Ishiguro is that rare combination of a commercial success who is also widely respected as a literary writer. But he also has a lot to teach us as writers.

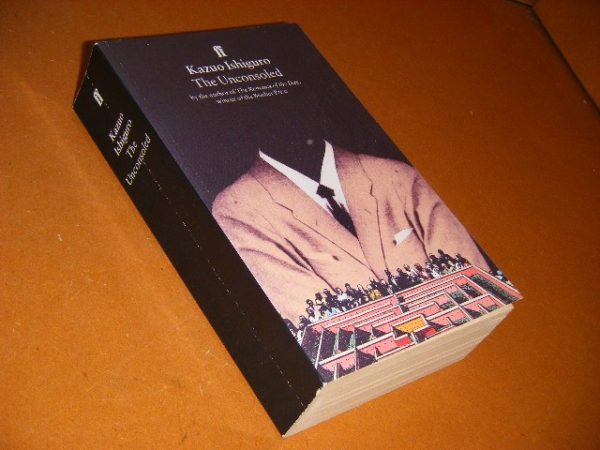

The Unconsoled

Ishiguro’s 1995 novel The Unconsoled depicts the visit of world-class pianist Mr. Ryder to the music festival of a small European city. Set over a few days, Mr. Ryder bumbles through the town attempting to understand the passions of the citizens in order to enhance his performance. He careens headlong towards the day of the music festival, and the events leading up to his recital are far from expected.

The simple summary of the book ends there. Any reading of The Unconsoled will be a deeply personal experience. Critics were divided as to the novel’s quality, either giving it lukewarm praise or panning it, with one prominent critic stating that Ishiguro had ‘invented a new level of badness’. Others, like me, found the book to be astoundingly innovative and skillfully written.

The goal of this piece is to assist writers (and myself) in understanding the craft of writing. The Unconsoled proves a wonderful text because it touches upon the conventional boundaries of the craft.

This article aims to tease out some of the innovative writing techniques presented in The Unconsoled. By the end, we should be familiar with the use of (1) formal language; (2) formal speech; (3) narration; (4) point of view and unlimited focus; (4) point of view and limited focus; (5) mood; and (6) authority.

What the Book is About

Perhaps the novel is better summarized in Kazuo Ishiguro’s own words. In a 2008 interview in The Paris Review, he stated:

There are two plots. There’s the story of Ryder, a man who has grown up with unhappy parents on the verge of divorce. He thinks the only way they can be reconciled is if he fulfills their expectations. As a result, he ends up as this fantastic pianist. He thinks that if he gives this crucial concert, it will heal everything. Of course, by then, it’s too late. Whatever has happened with his parents has happened long ago. And there’s the story of Brodsky, an old man who is trying, as a last act, to make good on a relationship that he’s completely messed up. He thinks that if he can bring it off as a conductor, he’ll be able to win back the love of his life. Those two stories take place in a society that believes all its ills are the result of having chosen the wrong musical values.

Whether or not you agree with Ishiguro’s interpretation, the plotline of The Unconsoled is, in truth, very difficult to summarize and secondary to the work’s explorations, which can be profoundly meditative, deeply disturbing, and downright hilarious. Very little is overtly revealed in the novel. Rather, a tremendous amount of responsibility is placed on the reader, who must sift through complex information with few guiding clues. The burden is further heightened by the fact that Mr. Ryder rarely accomplishes his aims, being frequently waylaid by old acquaintances and appointments. For example, the reader does not even learn that Mr. Ryder is scheduled to play the piano at the music festival until nearly two hundred pages into the text.

There is also a pervasive sense of the surreal throughout the work. Perspectives can be mutually exclusive, and aspects of the story that a reader might take for granted, such as a setting, can shift at any moment. Further, while Mr. Ryder explores the city with the perspective of a stranger, certain events suggest that he has been there before, perhaps even lived there for a time. A young woman and child, to whom Mr. Ryder at first speaks with curiosity, turn out to be his wife and son. His hotel room inexplicably contains a rug that he played with as a child in England; upon visiting a country estate, he discovers the old family car his parents drove overseas. But calling the text ‘surreal’ is to unfairly limit its scope. It is difficult to pin a label on The Unconsoled because the variety of characters, events, and sheer length defy easy categorization.

Readers looking for a point or the lessons of a buldingsroman will be disappointed; readers looking for an exploration of themes including memory, reality, family, and failure, may be more satisfied. I loved the book and only wish I’d bought it instead of taken it out from the library.

Learning the Craft of Writing from the Book

We will now turn to examine the text as writers and not as readers, with the goal of helping us become better at our craft.

Formal Language

The language in The Unconsoled is very formal. The narrator relates events in a detached tone, as if composing an essay, and the characters speak in a conservative manner. Sentences are written with grammatical precision. Instead of using the colloquial “I asked him who he was speaking to”, Mr. Ryder would narrate, “I asked him to whom he was speaking.” There is also a totally disproportionate use of the word ‘indeed’, which smacks of academia and formality. As in: “Indeed, as I crossed the square I passed many office workers standing in groups with their briefcases, talking cheerfully together.” (31)

This style of writing came as a surprise after An Artist of the Floating World (1986), a work of Ishiguro’s set in post-war Japan. In that text, the formal language felt appropriate because the character was Japanese (and hence translated) and the culture was steeped in an historical tradition.

The effect of formality in The Unconsoled is to give the European town a historical gloss. There is the sense that, despite the conveniences of a modern city, like the trams, the town could have existed fifty or even a hundred years earlier.

Standardizing the language in formality also affects other themes of the text. Holding certain aspects of the writing constant frees up the reader’s mind to contemplate unusual explorations. In other words, standardizing language in a formal tone permits the writer to guide the reader towards different themes. The reader does not become preoccupied with catching inflection in dialogue, and is thereby capable of digesting other layers of the story. In The Unconsoled, the steady drone of the formal language prepares the reader for forays into questions of reality. (I believe this can also be said of Haruki Murakami’s work, whose settings tend to be very trim and proper, whose characters are often cleanly dressed, only to have him zip them over to some parallel world.)

This is not to suggest that the formal language of The Unconsoled lacks beauty, or that it is boring. Rather, Ishiguro has a delightful, tender rhythm to his prose that is often punctuated by commas. We feel as if we’re drifting along:

The awning had shaded the glass, allowing a clear view through to the back, and Sophie had been visible sitting alone, a cup of coffee before her, wearing a look of utter despondency. (14)

Here the narrator is describing an emotionally delicate scene and the rhythm gives her ‘look of utter despondency’ an odd beauty.

However, while the formal style sets the reader at ease, the strange result is that very few lines stayed with me as I closed the book; nor did many of the lines make me want to remember them, as happens, for example, with James Baldwin. I left with the feeling that the text in The Unconsoled is woven like a tapestry, rather than the bright-colored patchwork that might be found in hard-boiled fiction. I remembered scenes but not their content, characters but not their manner of speaking.

Formal Speech

The formal language in The Unconsoled also pertains to the speech of the characters. Dialogue in fiction can range from attempting to be a precise copy of real dialogue to a paraphrase. A precise copy tends to be impossible to understand when put down on the page given the nonverbal communication in which people engage — real conversation includes all kinds of references, innuendos, and so on. The paraphrase may be found at the other end of the spectrum, giving little emphasis on the actual manner in which things were said. Then there’s a lot in between, sometimes called ‘free indirect discourse’.

Monologues

The characters in The Unconsoled generally speak in direct discourse, or with quotation marks. Some speech is summarized and certain dialogue is paraphrased, but what stands out in the work is the text contained between the quotation marks. The reason is that characters can talk for four or five pages without interruption (e.g. pages 82-85). This struck me with the character Gustav because, as a porter (and ancillary helper), I expected him to offer no more than a few phrases before Mr. Ryder entered his hotel room. But Gustav talks for several pages, and so do many of the characters.

Rather than being distractions, these long monologues are as important to the text as the ‘events’ which happen, not only because they inform the thrust of the plot, but also because the monologues are rich stories within themselves. In fact, I suspect that the reader’s patience for these monologues — and recognition of their intrinsic value — will determine whether she finishes the novel. It strikes me that that Ishiguro’s editor probably wasn’t thrilled with all of them. I myself had to set the book down for a week at about page 250, because I grew tired of the monologues ‘interrupting’ Mr. Ryder’s investigations. (When, again, the monologues were the investigation.)

Rhythm

But I also wondered: how did Ishiguro have the characters speak for so long without the dialogue getting boring or, worse, stilted?

I already mentioned the formal style. Unlike Walter Mosley, who captures what he calls black ‘dialect’ in his dialogue, for example in Black Betty, Ishiguro’s characters all use similar turns of phrases. This smoothes out differences of class and other information that is normally contained in dialogue, so that these distinctions must be explained in other ways. In other words, if you can’t tell how educated a person is from their speech, you have to depict where they live, how they’re dressed, and other things. There is certainly magic that cannot be taught in the monologues of The Unconsoled. What can be learned, or observed, is Ishiguro’s use of the comma, and terms which require it. ‘Sir’, ‘of course’, ‘in fact’, ‘you see’, and ‘well’ are frequently used. Then the characters pause on their own while speaking:

Well, that’s not quite true, he was also at the library. Two or three mornings a week he’d come into the library, take his usual seat beneath the windows and tie his dog to the table leg. It’s against the rules, to bring the dog in, but the librarians long ago decided it was the simplest thing, just to let him bring it in. Far simpler than starting a fight with Mr. Brodsky. So you sometimes saw him there, his dog at his feet, thumbing through his pile of books — always these same turgid-looking volumes of history. (110)

You can see that there’s a lot of variety in the passage even within the tendencies I outlined earlier. After a long sentence, the ‘Far simpler’ phrase breaks up the rolling gait, and there is a hyphen after ‘his pile of books’. The characters themselves also describe the setting in a way for which most people don’t have patience in a conversation. In the passage, this may be found in ‘take his usual seat beneath the windows and tie his dog to the table leg’, a very descriptive sentence. In real life, people, or at least the people I know, roll their eyes at such descriptions, finding them unnecessarily poetic. I think it’s fair, however, to state that this kind of rhythmic dialogue may be discerned throughout the text — and it works very well.

Narration

I am not a theorist, but I do know that narrators in a novel are inherently unreliable. Words on a page do not have a direct link with reality — the words have meaning only to each other. People may agree that the words can stand for something, but that’s it. The agreement alone does not inject reality into the words on the page. So every text has to be taken with a bit of skepticism, with an awareness that there’s a game at play.

In The Unconsoled, Mr. Ryder is an extremely unreliable narrator. He doesn’t recognize his own wife, his father-in-law, old friends, or his son. He is bad with directions, getting lost down corridor after corridor, and various clues hint that his forgetfulness, which borders on aphasia, is deliberate. His memory is poor, or selective, and he is also frustratingly passive, with his plans getting waylaid again and again by more assertive characters.

But Mr. Ryder is also fascinating in the sense that it becomes a joy when, in the gaps and lulls of his memory, he reveals something about himself. For example, the reader remains in doubt as to whether Mr. Ryder can actually play the piano at all, or if he is like Gary Larson’s cartoon, in which an elephant dreams of having to give a piano performance with its giant feet, when it considers itself a ‘flutist’. The insights that peter through the unreliable narration can be much sweeter and profound than with a trustworthy narrator.

Point of View

The text is narrated in the first person, with the pianist Mr. Ryder as the narrator. I used to consider writing in the first person an ‘easier’ point of view because we spend so much time in our heads, and, indeed, I still think — outrageously perhaps — it is the easiest format for a short story, especially one borne of a real experience because so many nuances are contained in the ready-made voice. That does not make the first person point of view any less valid, but I think it’s easy to become complacent with that voice.

However, first person narration in a novel is much different. Generally, the reader gets bored. A close look at good novels written in the first person reveals that there is narration in other points of view, or the author will play with media — including letters, newspaper articles, and other things.

Anyway, The Unconsoled is written in the first person. But I never got bored of listening to Mr. Ryder. This is partly because he was so often interrupted by the other characters, who ‘take over’ the story, rambling on for several pages.

Unlimited Focus: Voyeurism

There is another reason why the story kept my attention. There are certain instances in which Mr. Ryder receives information in an unorthodox manner. Examples are best here. Early in the text, Mr. Ryder remains in the car while his driver goes to meet another character: “Stephan got out of the car and I watched him go up to the entrance.” (56) The driver enters the apartment and has a conversation to which Mr. Ryder is not privy. Basic rules of space — there are walls between them — suggest he could not hear the conversation. Yet Mr. Ryder still describes furniture that is not visible and relates the conversation, presumably word for word:

“It’s to do with Mr. Brodsky.” “Ah,” Miss Collins said. “I rather suspected as much.”

The conversation continues as if Mr. Ryder is present in the room, when he is sitting in the car, and at no time does the narrator offer an explanation. The focus, which should have been limited to Mr. Ryder’s point of view, has become unlimited. This is an effective voyeuristic technique, causing the reader to ask several questions. Is Mr. Ryder’s gift, more than his piano playing, his ability to hear conversations through walls? What meaning is contained in such a conversation? I think the technique works because of the general mood Ishiguro has created (magic — can’t be taught) but also the formalized language I described earlier. The gentle rhythm of the language and pace makes the conversation digestible — though just barely.

Limiting Focus into Passivity

This voyeuristic technique is turned on its head not far along. In this instance Mr. Ryder is present during a conversation, but appears not to register the content of it. Arriving to meet two journalists for an interview, the one journalist speaks directly about Mr. Ryder to his colleague:

Remember, like all these types, [Mr. Ryder is] very vain. So pretend to be a big fan of his. Tell him the paper had no idea when they sent you, but you happen to be a really huge fan. That’ll get him.

Mr. Ryder does not react to this comment or others like it, to the extent that he is manipulated into posing before a controversial city monument. The focus of his point of view is broad enough to respond to the conversation, but he acts as if it is limited. Whereas his focus expanded in the earlier example, here it has contracted. He has become a mere fly on the wall. In the story, this technique serves to underscore Mr. Ryder’s passivity as a character. The reader wants the narrator to object, to say, ‘hey, don’t talk about me like that’, but instead Mr. Ryder offers no reaction.

The larger point is that the author has played with limiting and unlimiting the focus of Mr. Ryder. Earlier Mr. Ryder was not present but recorded a conversation; in this example he records the conversation but is not present. In a conventional story neither technique would be permitted without explanation. In The Unconsoled it works.

The Not-so-Conditional Conditional Tense

A final point of view technique that deserves passing mention is the use of the conditional tense. (‘I would do this if’, I would bite, I would write, I would play a flute). At certain points, Mr. Ryder narrates in the conditional and it is later revealed that what is narrated has actually happened in the text. This is especially odd because the use of the conditional indicates a hypothetical situation, an event that has not yet happened. An example of this may be found when Mr. Ryder plays the piano in a small shed in the countryside and hears digging. Without gathering any information, he determines that the shoveling is another character burying his dog, and somehow knows all of the details of the character’s actions before he began digging:

At first, naturally enough, Brodsky would have turned over memories of his late companion. But as the minutes had ticked by and there had continued to be no sign of me, his thoughts had turned to Miss Collins and their forthcoming rendez-vous at the cemetery. Before long, Brodsky had found himself remembering again a particular spring morning of many years ago, when he had carried two wicker chairs out into the field behind their cottage. (359)

Here the use of ‘would have’ indicates the conditional. Not only does Mr. Ryder guess what would have happened, he has access to Brodsky’s memories. This ability to expand his focus is never explained. The technique is especially compelling because, although Mr. Ryder’s own memory fails him, he can access the memories of others in detail. In a conventional text his insights might be considered a ‘plot hole’, but in the midst of the greater story of The Unconsoled, like the other techniques, the use of the conditional works.

Mood

As we saw in the rough summary in the beginning of this essay, The Unconsoled may be described as ‘dreamlike’. This is the term that Ishiguro himself used to describe the text in interviews. Critics have panned or celebrated the novel as ‘Kafkaesque’, owing to the protagonist’s passivity, to his faultiness of memory, and to the illogical thrust of the plot. In Kafka’s novel The Trial, the protagonist attempts to navigate a labyrinthine bureaucracy in the face of a criminal accusation. It is a nightmarish tale in which the narrator neither affirms nor denies the accusation, blundering through a suffocating society. I think classifying The Unconsoled as a surrealist work is fair, but a few techniques distinguish the work from pure surrealism or from pure Kafka.

Beauty in the Dream

Unlike The Trial, Ishiguro breaks the aimless amble of the story with serene beauty. There are lush descriptions of landscape, with open vistas and enjoyable descriptions of settings. Ishiguro has a particular talent, I think, for capturing the mood of a space — be it a room or an open field — and for describing sunlight, which in the hands of other writers can get boring and hackneyed. These descriptions are vital in keeping the writer at ease. Even in a nightmare, The Unconsoled demonstrates, there is the possibility of peace. There can be good food, there can be dancing, and there can be memories of favorite soccer teams.

Sleep in the Dream

A second distinction that precludes comparison to Kafka pertains to the use of sleep. After long, detailed conversations and the pinball trajectory of Mr. Ryder’s explorations of the town, he is permitted to sleep deeply. I was surprised at how allowing the character to sleep set my mind at rest and prepared me to take in more information. Most often, Mr. Ryder just slept, nothing more, without mention of dreams or symbolism. Surprising too, that the things which we find restful in real life can become restful on the reader’s page. And the odd effect was that when Mr. Ryder went to sleep, I didn’t — I wanted to read more.

Humor in the Nightmare

A final distinction from The Trial pertains to the use of humor. The claustrophobic mood of The Unconsoled is punctuated by scenes that are plainly hilarious. A few stand out: Mr. Ryder’s unwilling appearance as a guest at a funeral, where the mourners stop their bereaving to offer him peppermints (369); the hapless drunk Mr. Brodsky, who conducts an orchestra using an ironing board as a crutch; and, after Mr. Ryder parts painfully from his family, he consoles himself with a breakfast of croissants that are ‘extremely fresh and of the highest possible quality’. (534)

Authority: Writing about the Arts

Ishiguro is brave in that he explores the arts in his novels. In An Artist of the Floating World, the character Ono is a painter, and in The Unconsoled, Mr. Ryder is a pianist. I think it is very difficult to write about the arts without sounding pompous or tritely poetic. Somehow Ishiguro strikes the balance. When necessary, he reveals just enough information to convince the reader that he has done his homework, and the result is that one can concentrate on the characters instead of the art, which is merely supplementary. This is not always intentional. For example, referring to An Artist of the Floating World, Ishiguro admitted he was surprised by how people assumed his gaps of knowledge — what he didn’t know, not what was intentionally left out — stemmed from creative sensitivity and not ignorance.

Again, what matters is that it works. In The Unconsoled, I was, as a non-musician, satisfied that the author had captured the spirit of a pianist, whether or not he’d related the nitty-gritty. If the book had been purely about Rachmaninoff Piano Concerto No. 3, as in the film Shine, perhaps it wouldn’t have worked.

What Is Left Out

Conversely, Hemingway has stated that the reader can immediately sense what is not known by the author, and can also feel what is known. Better not to mention things at all, he posited, than to posture oneself as familiar with them. I would place Dan Brown’s ‘information dumps’ in The Da Vinci Code on one end of the spectrum and, perhaps, The Unconsoled towards the other end. They both work but I think The Unconsoled succeeds on a deeper level because the human experience, into which the novel delves with intricacy, is at center stage, and not the footnotes of historical texts.

Summary

The Unconsoled is a wonderfully inventive work that offers much to those looking to learn new writing techniques. Some of the techniques will likely never be used, but for me, it opened exciting new avenues for exploration. Kazuo Ishiguro has shown that conventions can be broken with tact — and a little magic.

**********

This piece was originally published in 2014 on Deji Olukotun’s Medium page.

**********

About the Author:

Deji Bryce Olukotun graduated with an MA in Creative Writing from the University of Cape Town, and also holds degrees from Yale College and Stanford Law School. He became the inaugural Ford Foundation Freedom to Write Fellow at PEN American Center, a human rights organization that promotes literature and defends free expression. His work has been published in Guernica, Joyland, Words Without Borders, World Literature Today, Molussus, The London Magazine, Men’s Health, Litnet, and international law journals. A passionate soccer fan, he grew up in Hopewell, New Jersey.

Photo by Beowulf Sheehan

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions