In August, we launched a fun series, “When Writers Talk Music,” where we collect what African writers have been saying about music. Previous posts featured Teju Cole’s thoughts on Fela and WizKid, Imbolo Mbue’s fondness for Soukous and Makossa, Petina Gappah’s cover of Bob Marley’s “Zimbabwe,” and Ainehi Edoro’s meeting with Afrobeat legend Tony Allen. This week, we continue with Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie proclaiming herself a fan of the Nigerian rapper Phyno and Ntone Edjabe declaring an interesting affiliation to Fela and Soukous music.

Read: When Writers Talk Music: Vol. 1 | Teju Cole on Fela and WizKid, Imbolo Mbue on Soukous and Makossa

What kind of music does Chimamanda like? We have an idea. In Americanah, Ifemelu and Obinze play Obiwon’s 2010 song “Obi Mu o.” We also know, from her appearance in the video of Kush’s Half of a Yellow Sun film soundtrack song “Let’s Live Together,” that she likes the groups’s four performers—Lara George, TY Bello, Emem Ema, Dapo Torimiro. And that she likes Flavour who is on the song’s remix, who, interestingly, released on his most recent album a song called “Chimamanda.” And that, well, Beyonce. In March of this year, though, when she sat for a chat on BBC Radio Sunday Morning Show, it was Phyno’s “Nme Nme” that she requested to be played. Here are her thoughts as captured on Adriez Journal blog:

Phyno is a young Nigerian musician who has become very popular, doing very well. I love his work, not just the song. This song makes me nostalgic for a certain kind of home. It makes me nostalgic for the idea of being in my ancestral hometown and maybe there is a wine carrying, which is a traditional marriage ceremony, and the gates of a compound have been flung open and people are walking in and out and they are all dressed up in very bright colours and the women have big ichafus, head-scarfs, on and there is just an air of content joy, content togetherness. So this song, every time I listen to it, it just makes nostalgic for that idea of home.

Read: When Writers Talk Music: Vol. 2 | Petina Gappah on Bob Marley, Ainehi Edoro on Tony Allen

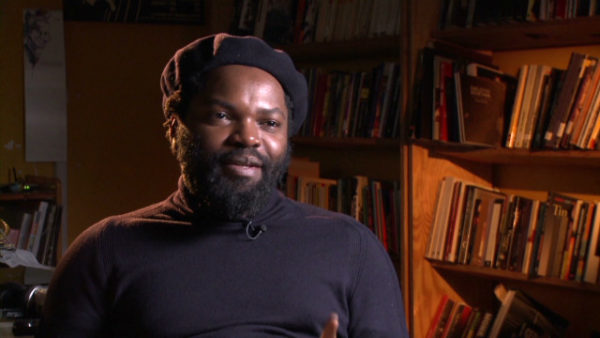

He’s Cameroonian, he’s a writer, journalist, DJ, he’s the founding editor of Chimurenga magazine, he’s a winner of the Principal Award of the Prince Claus Awards: Ntone Edjabe is one of our favourite literary persons ever. And being a DJ-writer means you have a lot to say about music. The following is an excerpt from a post on our blog about a conversation between Mr Edjabe and the Cameroonian philosopher Achille Mbembe at a 2013 Johannesburg Workshop in Theory and Criticism, in which Mr Edjabe says stirring things about Fela, Soukous music and politics.

2:35 Ntone leans back against his chair. He is relaxed and ready to play. Achille a bit less so, but he’s smiling and saying something to Ntone in French. The music has not been completely turned off. It’s playing in the background as Achille begins the conversation.

2:40 Achille: “You were born in Douala. You lived in Lagos. How is that you’ve chosen, of all places, to settle down in Cape Town?”

Pause.

2:41 Ntone: “Let me begin my response with music.”

Response is definitely odd in an academic setting where silences are awkward, where speech is the primary way of responding to an address. We all looked on, unsure, curious, expectant. A Soukous track comes on. Intoxicating in the way only Soukous can be.

2:45 – 4:00 Going back and forth between the seriousness of academic discourse and the playfulness of the DJ booth, responding to questions first with music and only later with words, playing music long enough to make us shifty on our seats. I say it’s all play on form, play perhaps on the form of the academic conference.

As Ntone told us about his journey from Doula to Cape Town and the founding of Chimurenga, I was struck by how often Fela kept coming up.

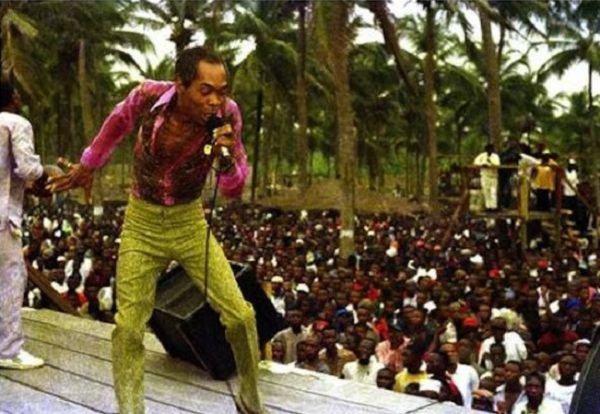

Ntone: “I never experienced Fela as a musician only but also as a radical thinker, a revolutionary. He confronted power whether it came in the form of military dictators like Babangida, religious leaders, Abiola, Thatcher, Botha. In Cameroun, I was used to musicians and poets resisting power but it was done indirectly by not naming things or giving things a new name. But Fela named things, named the enemy, named power.

By breaking the divide between the public and the private [Fela] expanded our vocabulary of resistance—the musician was no longer simply an entertainer.”

At one point, recalling the famous Fela quote, “Music is the weapon,” Achille says to Ntone, “If music is the weapon, who is the enemy?”

Read: Journal of An Awkward Academic or Music in the State of War

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions