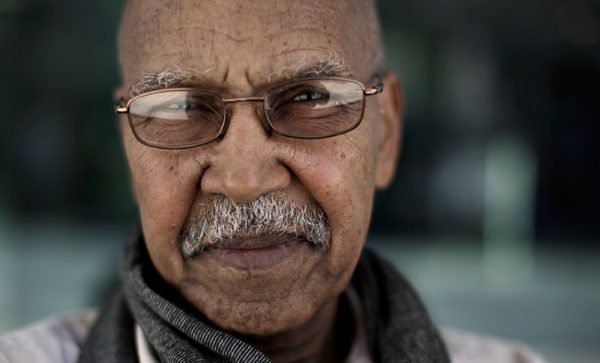

In 2004, Somalian novelist Nuruddin Farah and Ghanaian philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah sat for a conversation published in BOMB magazine. They discussed the state of things in Somalia then, how Farah learned to write, and why he chose English.

One of the best-known internationally acclaimed writers and considered a perennial nominee for the Nobel Prize in Literature, Nuruddin Farah is the author of thirteen novels: From a Crooked Rib (1970), A Naked Needle (1976), Sweet and Sour Milk (1979), Sardines (1981), Close Sesame (1983); the Blood in the Sun trilogy: Maps (1986), Gifts (1993), and Secrets (1998); the Past Imperfect trilogy: Links (2003), Knots (2007), and Crossbones (2011); and Territoires (2000), and Hiding in Plain Sight (2014). He is the author of the play A Dagger in a Vacuum (1965) and the nonfiction book Yesterday, Tomorrow: Voices from the Somali Diaspora (2000). Farah is a recipient of the Neustadt International Prize for Literature, the Premio Cavour in Italy, the Kurt Tucholsky Prize in Sweden, the Lettre Ulysses Award in Berlin, the St Malo Literature Festival’s prize, a UNESCO fellowship, the English-Speaking Union Literary Award, and a Corman Artists fellowship.

A leading philosopher and cultural theorist, Ghanaian-American Kwame Anthony Appiah is a professor at New York University’s Department of Philosophy and the university’s School of Law. He was named by Foreign Policy on its 2010 list of top global thinkers and received the US National Humanities Medal in 2012. He has further received the 1993 Anisfield-Wolf Book Award and the 1993 Herskovits Award of the African Studies Association for In My Father’s House; the 1997 Annual Book Award and the 1997 Ralph J. Bunche Award for Color Conscious; a 2007 Arthur Ross Book Award for Cosmopolitanism; The New York Times Book Review’s 100 Notable Books of 2010 and Times Literary Supplement’s Book of the Year 2010 recognitions for The Honor Code; and a 2011 New Jersey Council for the Humanities Book Award for The Honor Code, among others.

Read the conversation, and the introduction by Kwame Appiah, below.

*

I can’t remember where I first met Nuruddin Farah, but it was at some sort of conference. He told stories as we walked from one building to another—they were mostly about the South African writer Bessie Head—and by the time he had really gotten going, I had to beg him to stop because I was laughing so much it hurt. I knew his work already, of course, and admired it. He published his first novel From a Crooked Rib in London in 1970, at the age of 25, becoming, with that work, Somalia’s first novelist (though of course by no means her first great literary figure, since he was raised within a tradition of brilliant oral literature that can now circulate as audio recordings). Farah speaks not only Somali but also Italian, Arabic, Amharic, and, of course, the wonderful English of his nine novels.

He’s a writer who has written largely about one place—Somalia—yet manages to sustain a cosmopolitan vision. He’s a feminist novelist in a part of the world where that’s almost unknown among male writers. And even when he’s following a big story—about what dictatorship does to a society—he tells it through the lives of fully imagined women and men, and their families, their friendships, their vices and virtues; he tells it through what makes them individual, unique, special, and through what makes them like the rest of us, human. In 1974 he left Somalia to begin a period of peregrination of a sort that would have made sense to his nomadic Somali ancestors, though he has ranged over a wider territory, living in Europe, North America, and Africa. Two years later, he published A Naked Needle, catching the unfriendly eye of Siad Barre, Somalia’s dictator, and bringing about a 22-year exile that only ended five years after Siad Barre’s departure had plunged Somalia into a crisis from which it has still not emerged.

Farah and I often meet at conferences and keep in touch by email, and when we’re going to be in the same region of the world, we try to meet—he’s much in demand in the Somali diaspora and generously shares himself with his compatriots. His latest home is in South Africa, where he lives with his Anglo-Nigerian wife, Amina, who is a professor at the University of Cape Town, and their two kids. His most recent novel, Links (which promises to be the first novel of his third trilogy), was first published there last year and is forthcoming in April in the US from Riverhead Books.

When he visited New York last year, he came to our apartment in Manhattan and we talked (as you might expect two people raised in Anglo-colonial Africa to do) over a few cups of tea.

Kwame Anthony Appiah It’s Nuruddin Farah and Anthony Appiah talking on…the 22nd?

Nuruddin Farah Eighth. (laughter)

KAA Well, let’s start by talking about what you’re doing now.

NF I’m at a residency program in upstate New York, Art Omi, enjoying the quiet and rewriting a novel. I work in a very concentrated manner on a rewrite, working 18 hours a day, sleeping very little. This way I see where the weaknesses of the story are. I rewrite the novel as many as four or five times. I always start from the beginning and go through it without stopping, then put that draft away and three or four or six months later go back and rewrite it again more or less from memory.

KAA And you keep all these drafts?

NF I keep the drafts, some very bad, some not so bad, until I’m done with them all.

KAA There will be lots of literary archaeologists who would love to get their hands on the whole process.

NF I don’t think the drafts would be of much use to anyone. If you saw some of the earlier drafts, you would think I didn’t know how to write—and maybe I don’t. I write fast and then rewrite just as fast. For the first time, though, I’ve done a novel of about 570 pages and am cutting it down to 300-plus pages. Normally I work the other way around: I write a book of 100 pages and then make it much longer. What I hate most is to publish a novel very similar to my earlier ones. To make sure that that doesn’t happen, I convince myself that I’m new to writing, that I am doing it for the first time, in the hopes of producing something completely, absolutely different. To me anyway. I do that each time I write an article or a novel or a play.

KAA So the writing process doesn’t change depending on what the novel is about?

NF It is the method that is important. I approach writing as though it were a game that I play alone, in a room by myself. It’s not the most pleasant profession—how can it be? You lock yourself away in a room and face an empty page, daily. Writing, as a profession, is tedious, not very enjoyable. Nor is it highly appreciated, nor understood.

KAA So how did you come to be in this unpleasant business of writing?

NF (laughter) My interest in writing started long before I knew how one went about it. You could say it started as soon as I learned the first few letters of the Arabic alphabet, which I found most fascinating, as Arabic calligraphy decorated the walls of our houses. I was so enthralled that I kept copying them. And because many of our townspeople were illiterate, a large number of them believed that I was engaged in an activity that was rewarding. Even my parents linked my busyness to the sacredness of Arabic as a language, the tongue of the Koran—unaware that I was only taken with the script’s decorative quality, not its holiness. Somalis tend to be very religious but have no deep knowledge about the Koran or about Islam. Reading and copying became my means of escape.

Then I came into contact with secular writing in Arabic and was equally fascinated, in fact more so when I discovered that my name, Nuruddin, happened to be that of a prince’s in A Thousand and One Nights. Mischievous, I would cut Nuruddin out of every Thousand and One Nights copy that I got hold of (laughter) and tape them in my exercise books. Then I would boast to my playmates, “Look, I am a writer.” Later I showed similar interest in the English-language textbooks at the school I went to, which was set up by an American evangelical mission dedicated to converting us to Christianity. I would say that my first attempt at writing occurred when I was 15 and tried to recast a folktale in which rats plot against the cat that has been attacking them one at a time. In my desire to make the story mine, I replaced the names of the rat and cat characters of the folktale with the names of my classmates.

KAA (laughter)

NF I gave the good lines to the ones I liked and the bad lines to the ones I didn’t like.

KAA So you were retelling a folktale?

NF Reshaping it and imposing my own likes and dislikes upon it. By then, at any rate, my brother had given me books to read, Dostoyevsky and Victor Hugo in Arabic. He also gave me books in English that I was unable to read, let alone understand, because I had to underline every word, go to the dictionary and look it up. My brother then suggested that perhaps I should read the dictionary from cover to cover once a year, which I did for several years.

KAA So you had two languages as a child, Somali and Arabic, and then your brother got you into English. But you were quite serious about the Koran, weren’t you? And you know it very well.

NF My father was very serious about my learning the Koran. I was the fourth son. A tradition followed by families with many male children is to devote one of them to the study of the Koran and religion. I was the one chosen, assigned to the spiritual side of things. I had an excellent memory and could recite the Koran from beginning to end at an early age, so my father assumed that I would be good material. Unfortunately, though, my memory became unreliable the older I grew, especially when I started fooling around with some of the texts. You see, I was born toward the end of 1945, when a lot of the old traditions were being rejected or challenged, as was the case everywhere in the world. The world was changing from what it used to be to something that had never been known. All this was affecting our lives and our way of looking at the world.

KAA You were born when the Ogaden was under British control.

NF Yes, and my father was in the British civil service as an interpreter for the British governor. He was transferred from the town in which I was born, Baidoa, which had been Italian and then taken over by the British when the Italians lost the war, to the Ogaden. Then the British handed over the Ogaden to Ethiopia as compensation to Haile Selassie. By 1948, my father had saved enough from his interpreting job to start farming. He grew sesame, maize, lettuce, lemon, papaya.

KAA So your first memories were of the farm?

NF The farm was ten miles away from where we lived in town. I remember being taken there as a small child—carried on somebody’s back or shoulders. When I got bigger I walked, and helped on the farm.

KAA Since then you have lived in many places: India, Gambia, Nigeria, South Africa, Uganda, Germany, the United States.

NF Yes, but I have remained loyal to the idea of Somalia. I say that all the things I know about all the other places I’ve lived can be put into an article of about a thousand words, no more than that. Of course, I can set novels in these countries, but when you think about them seriously, such books will be of small literary value.

Read the full conversation on BOMB Magazine.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions