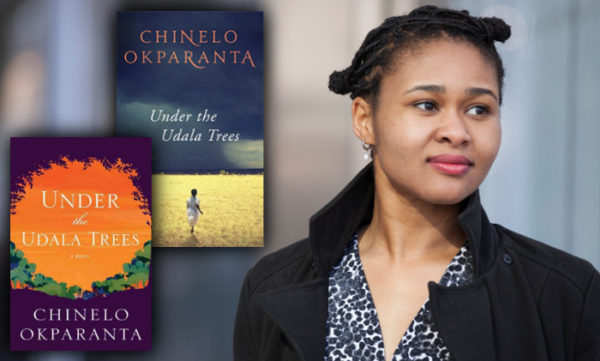

Chinelo Okparanta has been profiled by Sarah Ladipo Manyika for OZY, where Manyika is Books Editor. Titled “The Nigerian-American Writer Who Takes on Taboos,” the profile focuses on the reception of Okparanta’s body of work which explores queerness—the story collection Happiness, Like Water (2013), and the novel Under the Udala Trees (2016), which is the first by a Nigerian to centralize lesbian characters. Both books received the LAMBDA Literary Award for Lesbian Fiction, in 2014 and 2016, and serve as an entry point to the conversations around queerness in Nigerian literature. Okparanta is currently Assistant Professor of English and Creative Writing at Bucknell University, where she is also a C. Graydon and Mary E. Rogers Faculty Research Fellow.

Sarah Ladipo—recently the subject of a personal essay by the Zimbabwean novelist Tendai Huchu—is the author of the novels In Dependence (2008) and Like a Mule Bringing Ice Cream to the Sun (2016). The former, following its inclusion in the syllabus for Nigeria’s secondary school certificate examinations, and ensured by its publishers Cassava Republic’s piracy-beating tactics, has sold more than 1.7 millions copies in the country, as at November of last year. The latter became the first African novel to be shortlisted for the Goldsmiths Prize.

Read an excerpt of the profile.

*

When asked about the reception of her novel in Nigeria, Okparanta says it’s been mixed. At the 2016 Ake Arts and Book Festival, boos as well as cheers greeted one audience member who told Okparanta that “the natural order of life is against LGBT because the Bible said he [God] made male and female.” Okparanta, a self-identified Christian and a student of the Bible, not only questions some of the literal interpretations of the Bible but also refutes those who accuse her of being “brainwashed by the West.”

“Before the West decided that homosexuality was a sin,” says Okparanta, “I don’t think anyone in Africa, based on my research, thought it was a sin. Our own cultures were not against women-to-women marriages. My own grandmother was married to another woman.” Okparanta sees her writing as a way of “opening up conversations,” which is not to deny that just having those conversations can be difficult. She describes a 2016 radio interview in Lagos, where, “at the last minute, the radio host said, ‘Sorry, we can’t talk about your book because if we talk about it, we’ll be fined.’”

At the age of 10, Okparanta left Nigeria with her family and moved to America, where she recalls library visits for books as varied as Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cryand the Sweet Valley High series. It was in America, at age 11, that she won her first writing prize for an essay on domestic violence. “I grew up in a house where there was domestic violence,” she says. “And my research was interesting, now that I think about it. We had encyclopedias and such, but I also read Jehovah’s Witness publications.… As a child, when there’s a situation of violence, you don’t always understand it or have the vocabulary to name what’s going on, but by finding literature pertaining to that subject that matters to you, [you] might be able to find the correct term to name what’s going on.”

The vividness with which Okparanta evokes her childhood and domestic settings is a hallmark of her fiction. “She has a gift to evoke backdrop,” says Pulitzer Prize–winning poet Peter Balakian. “She’s able to infuse a setting and scene and dialogue with more than what appears.” And like the work of Okparanta’s former teacher, Marilynne Robinson, it is women and children that stand at the center of her writing.

Back at the 2016 Ake Arts and Book Festival, another audience member noted that Okparanta’s readers had a tendency to “dwell more on thematics than the writing itself.” For some writers, the thematics, or politics, of their work trumps craft, but not so for Okparanta. “Her art is always what art should be, which is truth and beauty rather than propaganda or rhetoric,” says Pulitzer Prize–winning novelist Paul Harding. “There’s a lucidity to it, an aesthetic truth to it that’s just astonishing.”

Read the full profile on OZY.

Amethyst January 10, 2018 03:01

I agree, precolonial Nigerian cultures never viewed homosexuality, queerness or cross dressing as unnatural or a sin. The British used the law and religion to make it illegal and taboo. So it baffles me when people talk without researching history.