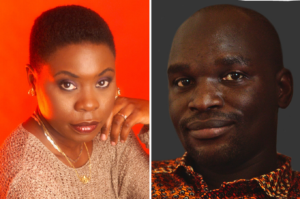

Describing himself as “first Somali, second Muslim, third gay,” the enchanting Diriye Osman is arguably the most fascinating writer on the African scene—he owns his identity, speaks his truth. A frank champion of other people’s work, his debut short story collection, Fairytales for Lost Children (2013), was awarded the 2014 Polari First Book Prize. His debut novel, We Once Belonged to the Sea, is forthcoming in September of this year.

In the brief essay below, titled “The Thrill of Literary Androgyny” and published on his Website, Osman uses the main character of We Once Belonged to the Sea—a lesbian—to intimate us on the meaning of “literary androgyny,” that gender-straddling sensibility possessed by the best storytellers.

*

In my debut novel, We Once Belonged to the Sea, the lead character, Señora Zahra, is an eccentric lesbian Somali artist who finds pleasure in expensive colognes, mink coats, and diamond-encrusted paintings. She is a fabulist who dedicates her life to the pursuit of refinement and revelry. I wanted to write about a queer black female artist that was obdurate about her proclivities and was, in many ways, celebrated for them. At a time when black folks like myself have to account for our black bodies, which is to say, our mere presence in the real and virtual world, I wanted to write about a queer black female artist in her prime who couldn’t care less about anyone’s approval, naysayers be damned.

Señora Zahra’s perfect foil is her protégé, Anissa Rouhani, a talented teenaged hijabi punk who finds herself grappling with her morality as she edges towards her creative goals. For Anissa, there is a tension between her desire to become a great artist and the Islamic faith which has sustained her during moments of self-doubt and trauma. This tension plays out in her coil-tight exchanges with Señora Zahra, who represents, in Anissa’s mind at least, the height of hubris and haramic shenanigans. It is a book about the intersection between art, faith, trauma and ambition.

The question that is frequently asked, however, is why write about these two women at all. Why not focus solely on the lives of queer Somali men? I wrote about these complex women because I understand this world. I grew up surrounded by strong, ambitious women and, as such, I’m familiar with this milieu. The prevalent Western perception of the Somali woman is someone who is meek and lacks agency. This narrative couldn’t be more contradistinctive to the culture I grew up in, a culture steeped in feminist discourse and dominance, a culture where the menfolk are often ancillary footnotes in the arcs of women’s lives. In my family alone, my mother, sisters, cousins, aunts and grandmothers were the keepers of the kingdom. It was always fascinating to witness family get-togethers where the men would pontificate about the state of Somalia and the women would sit down and analyze what needed to get done, which relative needed help, which youth was losing their way, whose sex life had stalled and, conversely, who was having the best sex of their lives. Whilst the men played politricks with their peers, the women formed a pick-sharp alliance, a sisterhood that was stronger than any marital bond. It was a sisterhood of love, friendship and carefree silliness spiked with spicy tea, comicality and clapbacks. I wanted to write a story that celebrated these kinds of relationships.

I am also a devotee of what Jhumpa Lahiri deemed, ‘a certain androgyny of the mind’. My favorite writers, from Edwidge Danticat to Zadie Smith to Donna Tartt, exercise this androgyny of the mind in their best work by writing from the male perspective. If writing fiction is a performance, it is important to imagine other lives, other ways of being. One must approach this responsibility, and it is a responsibility, with empathy and exactitude. One false note and the whole enterprise collapses in on itself.

Continue reading HERE.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions