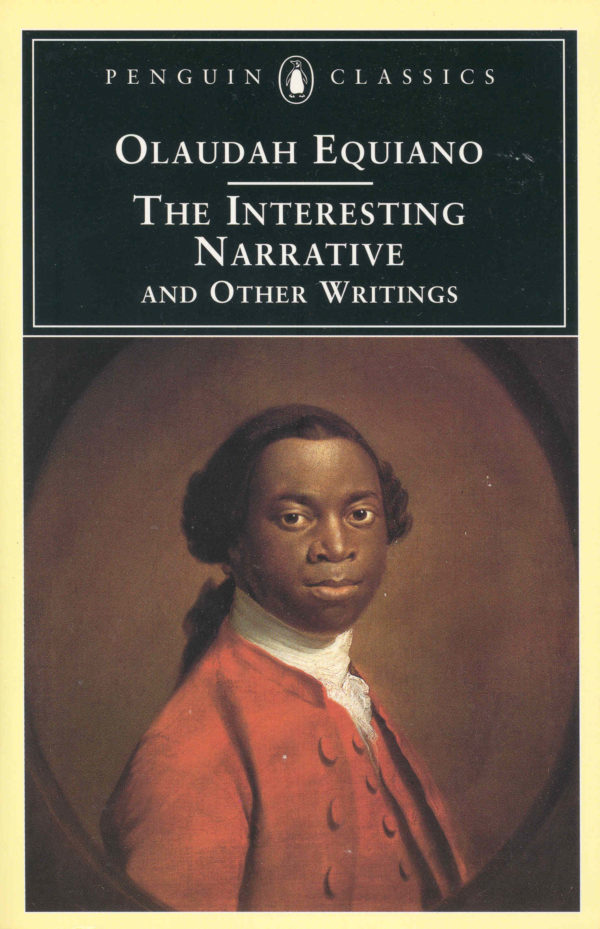

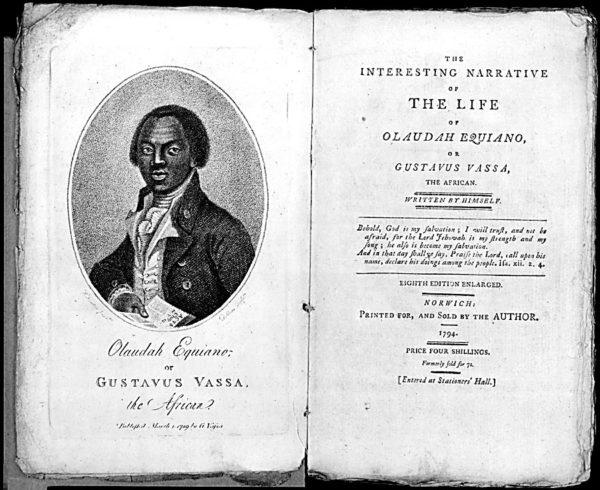

Olaudah Equiano’s 1789 memoir The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, Or Gustavus Vassa, The African has been named in a list of “the 100 best nonfiction books of all-time” compiled by Robert McCrum, associate editor of The Observer, and published in The Guardian. The list, reportedly, took him two years to get ready. Here is McCrum’s comment on the book:

The most famous slave memoir of the 18th century is a powerful and terrifying read, and established Equiano as a founding figure in black literary tradition.

Born in 1745, of Igbo extraction in the present-day Nigeria, Olaudah Equiano was kidnapped, sold into slavery, and shipped to England, where he he was given another name, Gustavus Vassa. Freed from slavery, he joined British abolitionists in campaigning against it. The publication of his memoir, which depicts the horrors of slavery, helped quicken the passing of the Slave Trade Act of 1807, which outlawed slavery in Britain and its territories. He died on 31 March 1797.

In an essay in August 2017, McCrum had written about The Interesting Narrative, placing it at No 79 on his list, and comparing it to Mary Seacole’s Wonderful Adventures of Mrs Seacole in Many Lands (1857), Peter Fryer’s Staying Power: The History of Black People in Britain (1984), and Henry Louis Gates Jr’s The Signifying Monkey (1988). He excerpted what he called “a signature sentence” from the memoir:

One morning, when I got upon deck, I saw it covered all over with the snow that fell over-night. As I had never seen anything of the kind before, I thought it was salt; so I immediately ran down to the mate and desired him, as well as I could, to come and see how somebody in the night had thrown salt all over the deck.

Here is an excerpt from his August 2017 essay.

*

Black literature begins with the slave memoirs of the 18th century. Equiano’s Interesting Narrative is the most famous of these, especially once it was taken up by supporters of the abolition movement, but he was not the first African slave to publish a book in England, or, if we remember Dr Johnson’s manservant, Francis Barber, the first to have some experience of London literary life.

In the book trade, Letters of the Late Ignatius Sancho (1782) were probably the first to mobilise English readers against racial discrimination and the horrors of the slave trade. Sancho would pioneer a flourishing genre that runs from Ottobah Cugoano in 1787 (Thoughts and Sentiments on the Evil and Wicked Traffic of the Slavery and Commerce of the Human Species) to Mary Prince in 1831 (The History of Mary Prince, a West Indian Slave). Thereafter, during the 19th century, black literature would continue to flourish, in Britain, with Mary Seacole (no 62 in this series) and, in the USA, with Frederick Douglass (no 68). In the 20th century, this tradition was sustained by largely autobiographical prose, often focusing on the imaginative reworking of the slave experience. Some outstanding recent examples include Grace Nichols: I Is a Long Memoried Woman (1983), Caryll Phillips: Cambridge (1991) and David Dabydeen: Turner (1994). All of these titles owe some intellectual debt to The Interesting Narrative.

Olaudah Equiano (c1745-1797), also known as Gustavus Vassa, was an African writer, born in what is now the Eboe province of Nigeria, and sold into slavery aged 11. Equiano subsequently worked as the slave of a British naval officer, purchased his freedom in 1766 and went on to write his popular slave memoir. No fewer than 17 editions and reprints, and several translations, appeared between 1798 and 1827. In hindsight, The Interesting Narrative became an influential work that established a template for later slave life writing and subsequently an important text in the teaching of African literature. Indeed, to Henry Louis Gates Jr, Equiano is a founding figure in the making of an authentic black literary tradition.

Inevitably, perhaps, The Interesting Narrative has been dogged by controversy from first publication. Equiano’s story was initially discredited as false (despite a preface including testimonials from white people “who knew me when I first arrived in England”). Even now, there are scholars who cast doubt on Equiano’s veracity, claiming that he plagiarised his story from other sources. Whatever the truth, the surviving text of his Interesting Narrative is sufficiently its own, in style and character, to merit serious consideration. Equiano’s story is certainly remarkable.

From the outset, he is concerned to establish his credentials as an ordinary, long-suffering African boy who has endured much and triumphed over adversity. He describes, at some length, the Eboe customs he has grown up with: circumcision, witchcraft and tribal patriarchy. As well as cataloguing his primitive beginnings, Equiano also celebrates the exotic and fabulous natural profusion of Africa, consciously playing to western fascination with the “Dark Continent”: “Our land is uncommonly rich and fruitful, and produces all kinds of vegetables in great abundance. We have plenty of Indian corn, and vast quantities of cotton and tobacco. Our pine apples grow without culture; they are about the size of the largest sugar-loaf, and finely-flavoured. We have also spices of different kinds, particularly pepper; and a variety of delicious fruits which I have never seen in Europe; together with gums of various kinds, and honey in abundance.”

Equiano, for all his modesty the hero of his own tale, also singles himself out for his natural eloquence. It’s his strategy in the memoir to convince his readers of the injustice of slavery by writing withal in a tone of reason and conciliation. While he can pile on the horror of the “middle crossing”, strangely, he lacks any resentment and does not castigate his white masters in print for their cruelty. His tone is nothing if not complicit: “I was named Olaudah, which, in our language signifies vicissitude or fortune; also one favoured, and having a loud voice and well-spoken.”

Read McCrum’s full essay HERE.

See McCrum’s full list HERE.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions