Fiction Title: Radio Sunrise

Author: Anietie Isong

Buy: Amazon

Great Britain. Jacaranda Books. 2017. 189 pages.

***

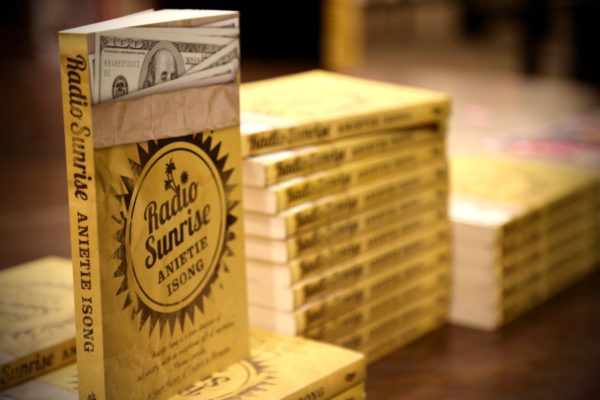

Anietie Isong in his debut novel Radio Sunrise unequivocally addresses unethical journalism. The striking cover page bears a picture of a wad of dollars atop a brown envelope and leads the reader into a story where flawed characters navigate the rough terrain of media commodification. The protagonist, Ifiok, criticizes media’s propagation of falsity and the misuse of public funds for political sycophancy but cannot effect change. Grieving the cancerous descent of journalism into a jolting wantonness that belies professional integrity in a society where media house directors are enslaved to the demands of power drunk politicians, the author portrays the necessity of a resolute fourth estate to uphold its professional ethics in a Nigerian state retrogressing under the weight of corrupt politicians and kleptocracy.

The novel charts Ifiok’s descent from ethical journalism to the status quo after his cultural drama The River (the last surviving cultural drama on Radio) is taken off air due to low funding. This amputation of passion and dream shoves the protagonist into a downward slide that sees him sacrifice interpersonal and professional integrity on the altar of self-interest. The prevalence of commodification for survival – journalists are selling the country one envelope at a time, media parastatal directors are in cohort with corrupt politicians, Niger Delta militants are fiercely agitating against government and oil exploiters, kidnappers are kidnapping dead bodies – raises urgent questions on governance, social responsibility and law and order. Ifiok’s swing to the dark side exposes a voracious society that preys on the upright with its suffocating systemic corrupt structures.

Radio Sunrise might be the first contemporary Nigerian novel to challenge and demand professional integrity from the media in this age of alternate truths and fake news. Isong’s language is reproachful, couched in terse sentences, short chapters and a prevalent use of dialogue. This style dramatizes the narrative even as its lean description leaves the reader thirsting, despite the theatrics of the bizarre and the sarcastic strategically dropped at vantage points in the narration. Talking of histrionics, the novel opens with the outlandish Nigerian myth of a stolen penis and closes with the familiar and alarming bombing of oil installations in the Niger Delta region – a recursive trend in the volatile region.

The slow violence and disaster capitalism in the Niger Delta region does not escape Anietie Isong’s gaze. The author stands on the shoulders of writers like Ken Saro Wiwa, Tanure Ojaide, Nnimmo Bassey and others to decry the ongoing ecological degradation, exploitation and its affect on the eco-indigenes of the oil-soaked Delta. The author contributes to the growing corpus of petro-fiction in Nigeria, a lineup chiefly populated by poets and academics. Through the eyes of the oscillating protagonist, we read: “The gas flares welcomed me to Ibok. Our big red scar that would not go away. Every year, the oil companies operating in my community and the government said they were discussing how to reduce flares. These discussions had started during my secondary school days.”

The author evokes Saro Wiwa, the Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People (MOSOP) and the Ogoni Bill of Rights in the letter sent by the Artisan Fishermen Association to the federal government demanding twenty four million naira in reparations because “the incessant oil spills from the facilities of Erand Oil in Ibok threatens our means of livelihood. The waters where they operate is equally our farm and each time there is a spill, we are thrown out of business” (162).

Longlisted for the 9mobile Prize for Literature 2018, Radio Sunrise problematizes societal decadence and suggests that the defunct amnesty skill acquisition program for surrendered militants was an effective starting point for violence reduction in the Delta but offers no remedy to the non-abating ecocide in the region or entrenched unethical journalism in the country.

**************

About the Author:

Kufre Usanga is a graduate student in the Department of English and Film Studies, University of Alberta. Her research focuses on orature and representations of the environment in Postcolonial narratives.

Kufre Usanga is a graduate student in the Department of English and Film Studies, University of Alberta. Her research focuses on orature and representations of the environment in Postcolonial narratives.

The slow violence and disaster capitalism in the Niger Delta region does not escape Anietie Isong’s gaze – Niger Delta Literature January 07, 2024 16:07

[…] Originally posted at Brittle Paper on January 29, 2018. […]