It is a brave new magical world. Women don’t just give birth to children here. They make them, out of whatever materials they can find, according to aspirations they wish upon the child, then take them to be blessed by a mother figure, after which they will come to life.

Ogechi, a woman formed from mud, is determined to give her daughter better luck in life by forming her out of the most exotic material. This burning desire pushes her to weave a baby out of hair, a creation that soon becomes a Dracula-esque monstrosity. In “Who Will Greet You At Home,” a tale that is part fantastical, part horror fiction, Lesley spins a dazzling web heavy with the weight of yearning, for love, for acceptance, for something better just a little bit out of reach. The story paints a brilliant diagram of the social pressures surrounding childlessness, the inscrutable sacrifices expected of motherhood, against the backdrop of ever present awareness, fear, and hurt that trail human interactions.

Most of the stories in this collection are focused on exploring the many fissures that time burrows into life, especially in familial relationships. In “Light,” a father tries to protect his daughter from the world and what it does, with full disclosure or implicitly, to girls, because “she is his brightest ember and he would not have her dimmed”, but eventually he bears witness to her light going out, and all his efforts sour before him. “Windfalls” renders the searing story of a girl, coached by her mother, and along with her, make a living from performing accidents, faking falls designed to look like they were caused by someone else so they could claim rewards from personal injury and liability suits. Lesley is adept at plunging the readers into a muddled pool of family history in just a few lines, suffused with a rawness that sits in the mouth like bile.

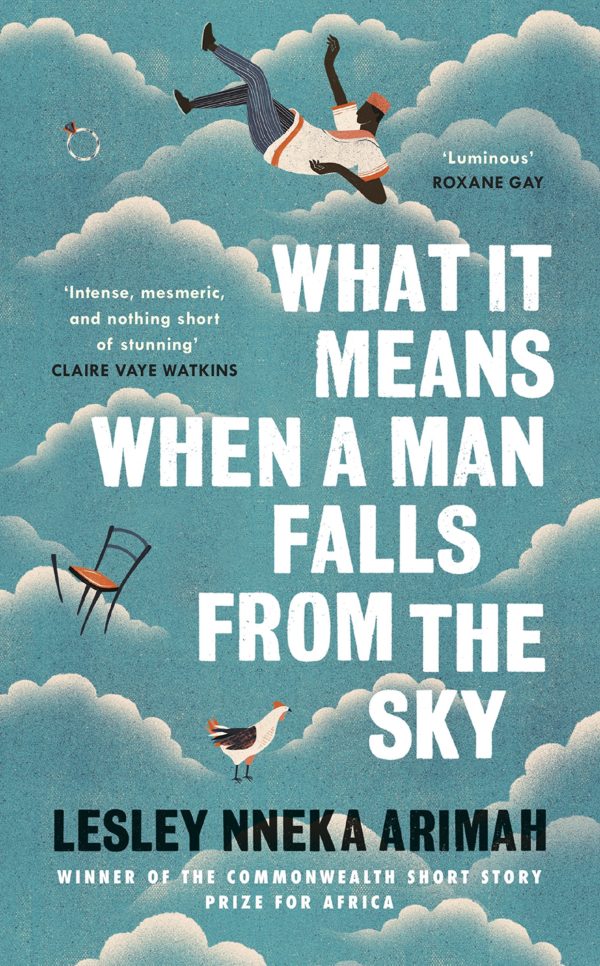

Set in Nigeria and the United States, “What It Means When A Man Falls From The Sky” competently examines the intersection between the personal and that which is shared with others, and the volatility of inhabiting both spaces: how much of living occurs in the things that are beyond one’s control – a vengeful visit from an embittered boyfriend, series of unfortunate events that meanders into one giant unexpected miracle, or the misguided lust of a pastor that can’t keep his penis in check; how hopes, ideals, ambitions, and relationships lose flavour when stirred by these underlying incidents.

In this collection, conflict is persistent, between the new and the old, past and present, traditions and modernity, mothers and daughters, identity against otherness, and these rivalries are articulated with a deftness that is wonderfully mesmeric, marking Lesley’s place as a remarkable storyteller.

The language that Lesley employs is simple, full of wit, and ingenious in the way it commits to possibilities, the mercurial nature of what is, the cruelty of what has been, and the constant modification and refusal of what is to come. At the centre of the stories, is an exploration of losses, vast and all too familiar: a mythic God loses her children and wreaks havoc on the earth to get them back until the grief numbs her into quiet acceptance; a father, saddled with the trauma of a country that once was and the people buried with it when it died, recounts memories long past to his daughter over games of chess; a daughter struggles to accept the reality, or forgiveness, of her dead mother who comes back to life. Again and again, Leslie reaches out for a chance to repair and sustain relationships made ragged by time, and complicated by the distance between places and generations in a voice that is razor sharp and achingly insightful: “there is this thing that distance does where it subtracts warmth and context and history and each finds that they’re arguing with a stranger.”

The characters Lesley has dreamt up are luminous and piercing, genuine and respectful images of the lives they embody. They grieve, negotiate belonging, and insist lovingly, if only by their intentions. In the eponymous story, “What It Means When A Man Falls From The Sky,” the world as we know it no longer operates. A new formula has been discovered, making it possible for mathematicians to calculate pain, and subtract it from the body, and braver ones “tried their head at using the Formula to make the human body defy gravity, for physical endeavors like flight” — cue the man falling from the sky. We’re drawn into this dystopian reality and forced to contend with what happens when human beings have and use such meddlesome powers.

This debut collection of stories is a commitment to tally human cruelty, grief, fallibility, conflict and ambition. It is an offering salted in knowingness, an invitation to come in, sit, and dine, with an unbroken promise that we will only depart full.

*****

Buy this book:

US | buy here

UK| buy here

Nigeria | here

*****

About the Reviewer:

Precious Arinze is a girl gone to woman too fast, and a freelance writer and researcher in her spare time, which is all the time.

Precious Arinze is a girl gone to woman too fast, and a freelance writer and researcher in her spare time, which is all the time.

Nneka Leslie Arimah is the Winner of the 2019 Caine Prize for African Writing July 09, 2019 00:01

[…] on the African literary scene for her speculative stories. Her remarkable story collection What It Means When a Man Falls from the Sky which was published in 2017, won the Kirkus Prize and earned her a place as one of the US […]