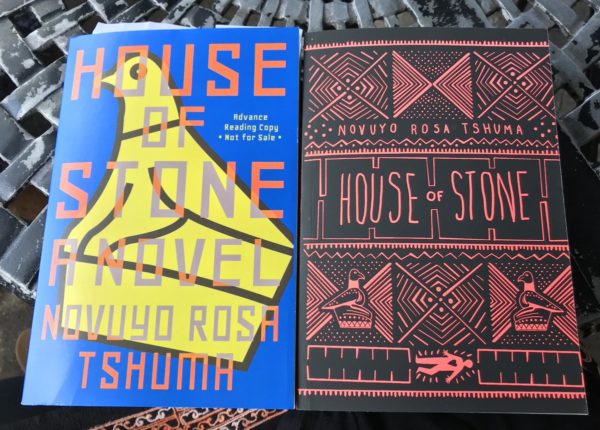

Novuyo Rosa Tshuma’s novel House of Stone, an exploration of family history, colonial Rhodesia, and the birth of modern Zimbabwe, was released in June, in the UK by Atlantic Books, and in South Africa by Penguin, and is forthcoming in the US from W. W. Norton in January, 2019.

The novel, which comes with blurbs from NoViolet Bulawayo (“Tshuma writes in an arresting and trenchant prose that shows a gifted artist at work”) and What Belongs to You author Garth Greenwell (“Novuyo Tshuma writes with an equal commitment to Joycean formal inventiveness and political conscience, and the result is absolutely thrilling”), now has a new admirer: Helon Habila.

Reviewing the book in The Guardian UK, where he traditionally reviews books by Africans, Habila describes it as “an extraordinary achievement for a first novel,” convinced that “Tshuma cannot write a boring sentence: she inhabits her narration so totally that the silliest actions are believable.”

Here’s an excerpt from the review.

*

This Zimbabwean debut is not an easy book to describe. To call it clever or ambitious is to do it a disservice – it is both, but also more than that. It is definitely not faultless, but it is large enough and unusual enough to shrug off its defects and still leave the reader impressed. The opening section features a tenant, 24-year-old Zamani, who aspires to make his landlord his father and his landlady his mother – to make them love him more than they loved their missing son, Bukhosi. A simple enough conceit, but Novuyo Rosa Tshuma is a wily writer, perhaps as wily as her main character; for as soon as the reader thinks he or she has figured out the story’s trajectory, the narrative takes an unexpected turn.

Bukhosi went missing in 2007, during a secessionist rally in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe. The protesters want to form a majority Ndebele republic, which they will call Mthwakazi, after a precolonial kingdom. Their revolt is fuelled by the massacre of the Ndebeles by Robert Mugabe’s government in 1983. This massacre, dubbed Gukurahundi – “the early rain that washes away the chaff before the spring shoots” – is Zimbabwe’s original sin, and here forms the central and recurring concern of the novel. Zamani was conceived, violently, symbolically, on the night of the Gukurahundi massacres. Tshuma exhumes her country’s history, starting with the arrival of Cecil Rhodes, through the vanquishing of Ndebele royals King Lobengula and Queen Lozikeyi, and on to the Ian Smith years as prime minister and the war of independence, and finally to independence and beyond. On the eve of independence on 17 April 1980, we see Bob Marley performing in front of the new black leaders, and police whipping and tear-gassing the masses, a foreshadowing of dark days to come: “The police, overcome by fear, slipped into animated violence like a second skin; they began thwacking the people with their batons, and the people wailed, so that their independence brimmed over into the night in a collective howl.”

Tshuma balances this broad retelling of history with the personal narratives of Zamani and his hosts, Abednego and Mama Agnes, through an almost dizzying ability to shift focus from character to character. Zamani uses whisky and drugs to seduce his “surrogate father”, who is a recovering alcoholic, into recounting his personal history – or “hi-story” as Zamani likes to call it, alluding to the fragmented and troubled past of his country.

Continue reading the review HERE.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions