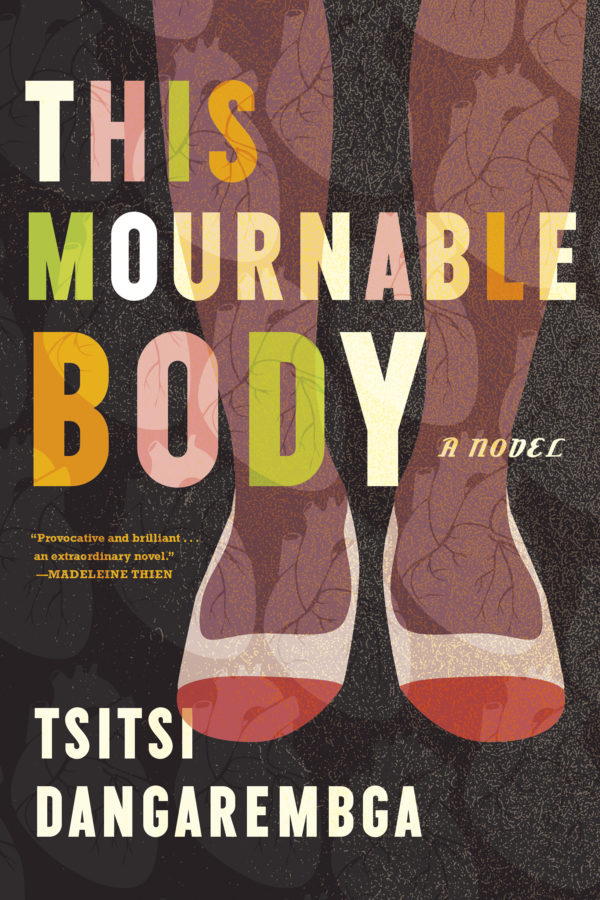

Earlier this month, we brought news of the publication of This Mournable Body, the final novel in Tsitsi Dangarembga’s Tambudzai Trilogy which includes the modern classic Nervous Conditions (1988) and The Book of Not (2006). The 296-page novel is published by Graywolf Press, and comes with a blurb by Canadian novelist Madeleine Thien, author of the Booker Prize-shortlisted Do Not Say We Have Nothing, who has called it “provocative and brilliant” and “an extraordinary novel.” This Mournable Body has further been praised by Vanity Fair, Kirkus Reviews, Publishers Weekly, and Booklist, among other notable publications.

A filmmaker and playwright, Tsitsi Dangarembga is the director and founder of the Institute of Creative Arts for Progress in Africa Trust. Nervous Conditions, which won the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize, was recently named by BBC among the top 100 Stories That Shaped the World. She lives in Harare, Zimbabwe.

This Mournable Body is available on: IndieBound, Barnes & Noble, and Amazon.

Here is an excerpt published on Literary Hub.

FOR THE first time since you left the hostel, or rather since you left the advertising agency on the pretence of marriage, your heart beats calmly in your chest. After your period of troubles, events are finally conspiring for you and not against you. This development that you desired so strongly is due, of all things, to your meeting with Tracey Stevenson. Scarcely allowing hope, you had prepared yourself as well as you were able for a much longer delay, only to have your wait shortened by your former colleague. Promising to keep in touch, she wrote down your number and gave you hers. You are satisfied that, concurring affably with everything she mentioned, displaying neither rudeness nor resentment, you played your part in reordering your affairs. You credit your first meal in the dayroom at the hospital for this beneficial improvement in your disposition. It was there that Widow Riley, confused as she was, revealed to you how perceptions, including of one such as you, do shift. This opened a crack in your estimation of yourself, through which you began a lethargic climb away from the lowliness to which you considered both born and condemned. Alone in your room, you laugh softly at the way the old woman took you for her daughter Edie. At your cousin’s, your new cheerfulness is further encouraged by your growing relationship with your white, German relative.

You are, you observe with satisfaction, the only member of the household who enjoys such contentment. Mai Taka enters the kitchen on Monday making an effort to appear grateful for the excursion. The poor performance is easy to see through and Nyasha soon extracts from the help the news that, yes, she did sit down with little Taka on the evening of the outing to charm her boy with Anansi’s antics. Silence, however, had barged in and forbidden Mai Taka to fill the boy’s head with foreign nonsense. The next day he took Taka away with him. Mai Taka had not seen either of them since and would have been at her wit’s end had she not received a message from her sister-in-law, whose son worked a few roads down, that Silence had deposited the boy with his grand-mother, but that since he had not left any money for the boy’s upkeep, Mai Taka should forward enough for the school levy, as well as Taka’s birth certificate if she wanted the boy to continue with his education. Silence himself did not come home, so that she suspects he had spent the rest of the time in the arms of his fourteen-year-old lover. Mai Taka announces that she is relieved to have been spared a beating and observes it is like a blessing in disguise that her husband seems to have absconded. In conclusion she declares her only regret is not having taken her son to her own mother, but she philosophizes there is not much she can do about it, as a child, when the father is known, belongs to the paternal family. Concern over Mai Taka adds to Nyasha’s worries over her workshops and her family.

For your part, uplifted by inner serenity, you surge with energy. There is not much into which you can channel your new vitality. You take to stargazing at night when the family has retired. You consult a children’s encyclopedia that Nyasha and Leon have bought your niece and nephew, hoping for useful diagrams, but it is in German and concerned exclusively with the Northern Hemisphere. When Cousin-Brother-in-Law learns of this, he remembers an old Birds of Africa he purchased while in Kenya. It takes him several days to find it, but when he does, you spend long stretches with Cousin-Brother-in-Law’s book and binoculars sitting on your little balcony, ticking off in pencil against their photographs the species that visit your relative’s garden. Each morning you wake much earlier than has been your habit to hum softly if shrilly the birdsong of a turquoise-breasted starling that sits in one of the custard apple trees by the garage and chatters. You pop into the garden to see whether you can identify any other avian company and when this is done, you return to make yourself a cup of coffee.

“Mangwanani, Maiguru! Marara here?” Anesu and Panashe chorus as you enter one morning soon after the outing to the cinema.

You step over the glistening annelids on the floor and pick up a bottle of filtered water, which you empty into the kettle.

“Panashe, for goodness’ sake, get on with it.” Nyasha scowls at her son, appearing not to have heard your murmured greeting. Your nephew stares back at his mother, who, day by day, is growing more frazzled.

Anesu swallows a mouthful of porridge, wearing a contemplative expression.

“You sometimes have a tummy ache, right?” she asks her brother eventually.

Your niece keeps examining her brother. A drop balances on the rim of his eye, then splashes out.

“You have one now, don’t you?” Anesu demands. “It’s hurting, isn’t it?”

A flood of tears soaks Panashe’s face.

Anesu turns to her mother and says in an accusing voice, “You see, it’s when you shout at him in the morning. That’s why. It makes his tummy hurt.”

“I didn’t shout,” says Nyasha curtly. She slits open a packet of red sausages that she intends to pack for her children’s snacks.

“You did, Mama,” an adamant Anesu points out. “That’s why he hasn’t done his shoelaces.”

“You, young lady, and you too, Panashe, get on with it,” Nyasha orders. “I’ll do the shoelaces when he’s finished eating. He’s got to get some breakfast inside him.”

Anesu balances her spoon on the edge of her plate. “It’s only because he’s frightened,” she says.

She takes another mouthful of porridge before she continues, “He’s done them before. He just doesn’t want to go to school today. That’s why he can’t remember how to do it. He doesn’t want his tummy to ache. Mama, his teacher makes his tummy ache too because she always hits the children.”

Your cousin dabs a red sausage with kitchen paper, packs it in cling wrap, as though she has been concentrating on the task too intently to hear. A moment later, she puts the food down in shock.

“Hits? The little ones?”

“In Germany it is illegal,” says Cousin-Brother-in-Law.

Your cousin looks as though she is about to sob, once again situating herself beyond your understanding. Weeping alongside a first grader—even nearly doing so—is a nauseating act of ghastly femininity. You have no desire to expend energy on sympathy for a minor matter of corporal punishment. Women in Zimbabwe are undaunted by such things. Your cousin, on the other hand, has been enfeebled by her sojourns first in England then in Europe. Acquiring a degree in political science at London School of Economics, another in filmmaking in Hamburg, and coming back to Zimbabwe where no one wants her to have either has caused her disposition to grow yet more fanciful. Zimbabwean women, you remind yourself, know how to order things to go away. They shriek with grief and throw themselves around. They go to war. They drug patients in order to get ahead. They get on with it. If one thing doesn’t turn out, a Zimbabwean woman simply turns to another. Your head overflowing with such thoughts, you are pleased that your meeting with Tracey and your subsequent peace of mind over it prove that you are a true Zimbabwean woman. You suppress a shudder of pity for your cousin, who, notwithstanding her education and ideals, will never amount to anything. Nyasha does not belong. Like her husband, she is a kindly import. For the first time in your life you feel significantly superior.

Nyasha walks across to Panashe and pulls his head to her stomach as though she believes that the other side of it is the only place the little boy will be safe. Since he is sitting at the breakfast table, this is uncomfortable for your nephew, but he endures.

“Because of our past, we are people who understand how instincts can easily become brutal,” says Cousin-Brother-in-Law. “We know such a thing must be stopped before it begins. We do not allow teachers to beat other people’s children. Nobody is allowed to beat children.”

“How are the children taught?” you ask. “How do they learn anything?”

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions