Teju Cole is a Great Essayist. We know.

The essayist-novelist-photographer-art critic was recently in Lagos, we reported last month, for an event at Jazzhole. There, he was in yet another enlightening conversation with TheNews/PM News Executive Editor Kunle Ajibade, reading from his 2013 Granta essay, “Water Has No Enemy.”

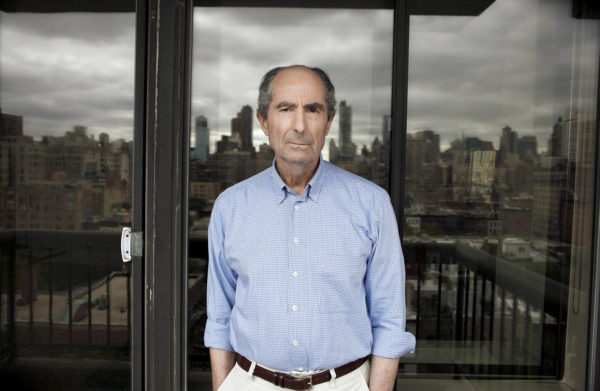

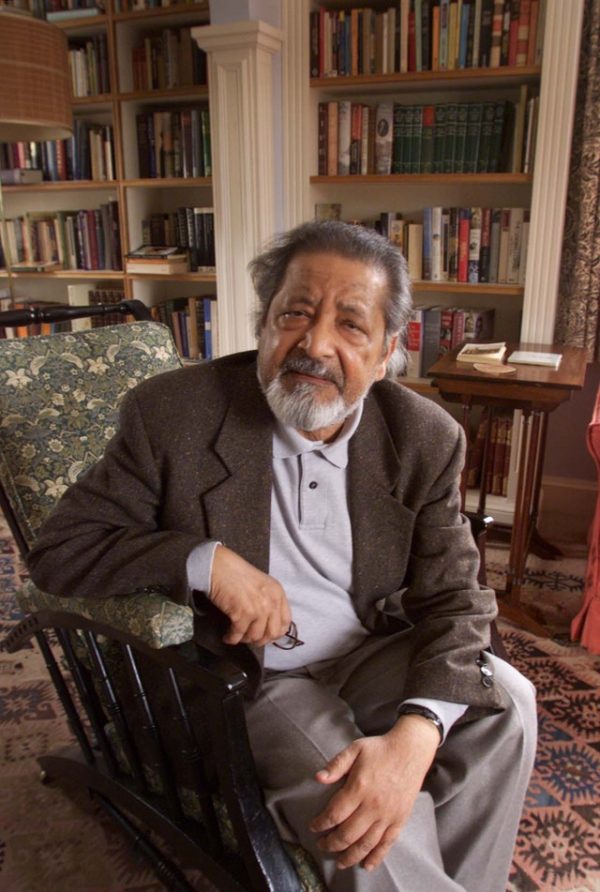

Midway, Ajibade asks Teju about his writing being loved by Philip Roth and VS Naipaul both of whom passed on this year. If you expected Teju to talk about whatever it is you expected him to talk about, you were wrong. Here is an excerpt from the conversation published in Premium Times newspaper.

Kunle Ajibade

Philip Roth was once asked in an interview just before he died to name writers he really enjoyed reading, and he mentioned your name among two or three other authors. V.S. Naipaul (and his publishers) also invited you to write an introduction to one of his books. Now, these two men can’t be more diametrically opposed, but both of them found something in you and your work to speak about. I’m curious to know what you think you represent to these two men that they can point your work out in a very distinctive manner?

Teju Cole

When you’re read by writers like Philip Roth or V.S. Naipaul, that’s not something you plan on. Let me tell a little story that I think could be encouraging to young authors in the audience. As you know, I finished secondary school in this city. Coming into my own as a writer, I would say the priority has been to do the work and to do it to the highest possible level. While my peers were trying to win story contests, submitting stuff, I never submitted anything. I spent all my time reading and writing and refining my art, my detector, so that I know if the work is good or not. If you know there’s something you need to put into the world and you need to put it into the world in a very intense and precise way, in a highly elaborate and thoughtful and committed way, then you’re going to do everything possible to make sure the work is up to scratch.

I met Philip Roth a couple of times. I didn’t particularly know him, but I was invited to his funeral and I went. While I was standing by his graveside, the service was over and people had retired over to reception/refreshment, a woman I didn’t know, an old lady, came up to me and said, I’m so glad you came. Just before Philip died, the last time I saw him, he wanted to discuss your essay about James Baldwin and he particularly liked that part . . . and she started to tell me in detail. Now, she’s telling me this while I was looking at the man’s coffin inside the grave with some handfuls of earth on it. A couple of things happened there for me. One is that I was immensely moved. Another thing that occurred to me was: whatever thing that got me to that point, I need to keep doing it to the best of my ability. What I tell my student is, I could give you email addresses but what good would they do you? Those people have not shut down the gates; it’s not as if they know all the artists already so they are not looking for new ones. They are always looking for something new.

The opportunity of being read by somebody you really admire is not enough reason that your work is ready yet. My word of encouragement therefore is: be ready. Don’t think if this person reads my work, then I’m made. No, your work is going to make you. And if you are fortunate enough for them to read your work after it has reached that level, then things can come together. And if they never read it, then it’s fine. You still made it. Just get it good, very good. It would be terrible if somebody told me that one of the last things Philip Roth read on his death bed was my work, and I’m thinking: I wish I had done better on that essay.

Teju was also asked about accusations of Afro-pessimism in his work.

Kunle Ajibade

Some of those who read that Granta essay on Lagos and your novella, Every Day is for the Thief accused you of Afro-pessimism. What is your response to their accusation?

Teju Cole

I stopped worrying about that stuff a while ago. I think we do have a responsibility to project stories in their complexities. We do the best we can. And when you’ve put all the layers into the story, you go back and put another two or three more layers because you never quite get enough complexity. But when writing also, you cannot cater to the concerned trolling of people who don’t really care. I mean people speak out of their bitterness, and so the first responsibility is to do the best pieces of writing – have them stand by themselves.

Commentary is cheap and easy and it’s hugely abundant. So it worries me a lot less now. This story, for example, is part of the material I’m working on as I think of a long form of non-fiction about Lagos, but I’m very much in doubt about whether this is the direction I want to take it in. Do I think it works as a piece that I want to do an entire book on, about Lagos? It could work but I feel a greater sense of responsibility to continue pushing myself to what I can try to do with language.

Yes, the story is coherent; I think it’s complete, but it’s dissatisfying to me, which leads to my own criticism because no one can critique my work more stringently than I critique them myself and, very often, more than an accurate critic. Categories like Afro-pessimism are just a little bit empty, sometimes. Lagos is shit; people really suffer, so we are not going to paint a picture that makes it look rosy. But on the other hand, when you acknowledge that Lagos is shit but it’s our Lagos, and we take care of each other a little bit, that’s also largely a relief. If you do something that has many layers and some people just have a tag-line to describe it, then they are not talking about you. They are talking about themselves.

Read the full conversation HERE.

Graph image of Teju Cole from Sydney Morning Herald.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions