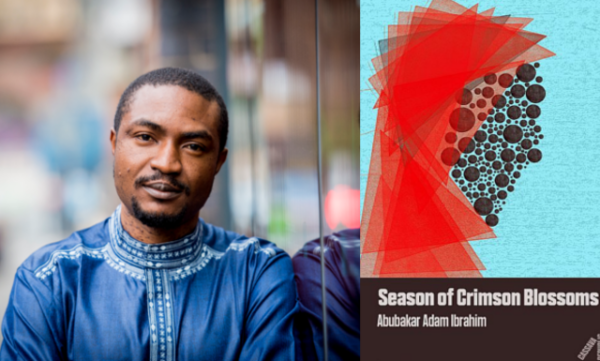

Abubakar Adam Ibrahim is now a national superstar. His first novel, Season of Crimson Blossoms, won the 2016 NLNG Nigeria Prize for Literature, which at $100,000 is Africa’s richest literary prize. For a book first published in Nigeria, it’s phenomenal that it’s gone on to be released in the UK, the US, India, and France, among other countries. These days, he can even count the former French president Nicolas Sarkozy as one of the lovers of his book. In the words of the moderator of today’s event, “He has gone global.” It is true. But you’d think it would be enough to pull a crowd to his reading of his prizewinning book on a dry December evening in Abuja.

Perhaps because the reading is in Maitama, one of the city’s most expensive districts, some distance from the other end of the city where most people live. Perhaps because the event is scheduled to take place from 5:30-7:30 p.m., which means some people will still be at work or about to leave for their homes. Or perhaps because the book is now three years old, and people are no longer as keen as they once were. Whatever the reason, it disappoints me, a little, that I do not find the crowd I expected. Of course, there’s a considerable turn out, but as I find out, much later, that the audience is mostly made up of writers or people in publishing. I yearn for a time when it will be a regular occurrence for a writer’s event to gather as many people who are simply readers as a Davido concert will more people who are just music lovers.

***

I get off the taxi at Café de Vie, the upscale restaurant hosting the event. I can hear music floating from within the premises, live music. Someone’s singing beautifully, strumming a guitar so masterfully that I forget that the taxi driver is yet to hand me my change. The driver calls my attention, asking if this is a club. I tell him it isn’t. I can see he’s contemplating the white people making their way into the premises. Maybe he’s also wondering whether I, this young man who read from a book throughout the ride, is suited for a place like this. Maybe; it’s all assumption, but there’s something about the way he’s looking from me to the café.

I walk through the gate and immediately spot Abubakar. It’s my second time seeing him. The first time was at a hotel, during an Abuja Literary Society meeting, but I hadn’t walked up to him as he had around him people I assumed were friends, laughing, talking. What point would there have been in interrupting them?

Today, I look away from him, taking in the environment, particularly watching the musician. Balanced on a high stool and cradling his guitar, he sings a beautiful cover of an Asa song which I do not now remember.

***

There’s a signing queue of three people in front of Abubakar. He sits by a table on which there’s a stack of his books. He’s wearing jeans trousers, a shirt, and his signature scarf, which reminds me that I’ve always thought he dresses like a boyoyo, if you know what I mean. I join the signing queue, noticing that, to my left, is a place that looks like a bookstore. I ask the closest attendant whether the books are for sale. She nods. I ask if I can look at them. She seems a little uncomfortable, but then confers with a white woman, whom I later learn is the owner of the place. She returns to tell me that it’ll be best if I look through after the day’s event. By the end of the reading, I’ll have forgotten.

***

Everyone on the signing queue is holding Cassava Republic’ edition of Abubakar’s book. That’s not the edition I have. I have Parresia Publishers’ edition, and Abubakar is no longer with them. When it’s my turn, I complain to Abubakar about this.

“Hello, evening.”

“Evening,” he says, attentive, seeing there’s something I want to say.

“Erm, I have Parresia’s edition of your book. I hope you’ll sign it?”

He smiles. “What makes you think I will not sign it?”

“I don’t know. I just thought. . . .” I feel the awkwardness of the moment.

But Abubakar is still smiling, what I can tell is an effort to make me feel at ease. “Of course, I’ll sign it,” he says, “it’s just that yours is 2015 and this is 2018.” And he says something about how this is the present and I’m still stuck in the past. We laugh about it. I give him the book, and it occurs to me that Abubakar must be adept at doing this: making his readers feel calm around him, even genial.

“What’s the name?” he asks, pen ready.

“Ikechukwu,” I say, immediately offering to spell. “I, K—.”

“No, I know it,” he’s writing already. “You know,” he looks up when he’s done, taking up a bass voice and singing the line in rapper Ikechukwu’s eponymous 2007 track: “My name is Ikeeechukwuuu!”

We’re both laughing. A memory flits by: it’s my brothers, hunching their shoulders in my face the way Ikechukwu does in the music video, singing in their fake bass voices: “My name is Ikeeechukwuuu!” I wave off the memory, but not the smile it brings.

I tell Abubakar my surname and again offers to spell; he won’t allow me. He knows someone back in the university—a course mate or a friend, I can’t remember which—whose surname was Ogbu.

This is impressive, I think, until I see him scribbling away in my copy of his book. I’m intrigued. I can’t make out from where I’m standing what he’s writing, but I’m intrigued at how he’s taking his time to produce a beautiful cursive writing. The way he’s forming each word, it’s as though if he misses the curve of a letter, something might shift in the atmospheric condition of the city.

***

I leave to find a seat and immediately spot an old friend, AS, a fellow writer. We exchange pleasantries and I go over to take a seat. Just then, I take out my book from my backpack to see what Abubakar has written:

Ikechukwu Ogbu,

Pleasure meeting.

Be so 2018 and beyond.

Best,

[His signature].

I smile, put the book back in my bag and wait for the event to begin.

***

We all sit at tables of fours. There’s a smattering of white people; most of the audience is black.

The moderator is superb, which is a relief, really, because it’s not every time one gets this at a literary event—you’ll be shocked. Or maybe I’m just the critic an old colleague used to insist on calling me, because, as she once put it, nothing escapes my eye. But, to be honest, the moderator today is so capable that I unusually feel so relaxed; not once do I cringe at a question he asks, nor suffer an entire minute of a moderator’s stuttering, trying to ask the right question.

He begins by reading the biography on Abubakar’s book, after which he asks Abubakar if there’s anything he’ll like to add.

This Abubakar is different from the one who has signed my book; the transformation is instant and obvious. He’s, this time, contemplative, even hesitant, as if he’ll rather say the right thing or none at all. He says that he just wants to add that he’s not Hassan Reza. We all laugh, but I check myself. Did I think there were similarities between the writer and the character, Reza, when I read the book? I didn’t, but from what Abubakar says next, it’s easy to see why people think so. Both writer and character are dark-lipped. Make of that what you will.

The moderator asks Abubakar that from the responses he’s got from readers, what aspect of the book—plot, character, scene—have most people been interested in discussing. Abubakar smiles before saying that readers have mostly been interested in discussing—well, you-know-who—Hassan Reza.

But what of winning the NLNG Prize, the moderator continues, all that money—how has Abubakar been able to cope with people who might feel entitled to the money. We laugh, because we know what’s coming. The guy closest to me nearly slumps on his chair, laughing. We know how many Nigerians will feel entitled to all that money if they’re related to Abubakar in any way.

Abubakar speaks of phone calls from people he’d not heard from in years, asking for school fees, medical bills, etc. As for the moderator’s question about whether he’s thought to “give back to society,” he laments for about a minute, saying that he did think it was important he did something of the sort, except that he wasn’t sure he had a good structure on how to go about it. So he committed funds to people he saw had these structures, but that thing about people and money happened. We are made to believe that the said people embezzled the money. Abubakar insists on not mentioning names, but I want him to, even though I’ve always been suspicious of the culture of calling out on social media.

***

As the evening goes on, the restaurant serves wine, fruit juice, chips and some exotic meals I’m still trying to learn their names. I eat them nonetheless. I need to know how they taste just in case a character in my book needs to go all Western. But I wonder why the guy seated close to me does not seem interested in anything. I’m sure he’s a poet. Don’t ask me why I think that. Because, of the four people on our table, he’s the only one who collects only a glass of wine and would not even drink it. Is he putting up a front or simply not interested? Anyway, people’s etiquette should not be my business, but still.

***

During the Q & A session, a lady asks Abubakar how he was able to craft believable characters. Abubakar responds that he lives with his characters, has a relationship with them, fights with them. A romantic, typical statement from a writer, which is what it is.

When it’s my turn, I ask him about what I think is an extraordinary feat: his attaining global recognition while living and writing from Nigeria, adding that, usually, it’s the other way around, African writers who live and are published abroad, sending their works back home. Does he think many more young writers can achieve global recognition while working from Nigeria? Add to it the fact that there’s been a recent surge of young writers traveling to the UK and the US to do MFAs.

The moderator says, “What a profound question!”

Maybe it’s indeed profound, but it’s not spontaneous. In truth, it’s a matter I’ve recently begun to think, even worry, about. Exactly a week before, I brought up the matter during a reading among younger writers and, during and after the reading, we talked about it—TJ Benson, Basit Jamiu, Tolu Daniel, Adefolami Ademola, and I. The consensus we reached was that all of these writers jetting out were already damn good writers, but in the MFA programmes, they were going to get opportunities they’d otherwise not get in Nigeria. So, the question was: why weren’t these opportunities in Nigeria?

Today, Abubakar says that he can understand why the generation before him moved to the West, because there was a collapse of the publishing industry. But that there’s been a recent shift, helped, in part, by the Internet. These days, your story can reach anywhere if it’s good, he says. Also, he adds, the Achebe and Gordimer generation wrote from the continent.

***

At the end of the evening, after Abubakar reads from his book and answers more questions, I return from using the bathroom to find AS, who immediately tells me that Abubakar is right, that she’s always thought one has to start from home. I see her point, and Abubakar’s, too.

AS and I live on the same axis of the city, so she asks if I’m ready to go home. I tell her that I quickly needed to say something to Abubakar, who I find signing books for readers.

I ask him if it’s okay to send him a Facebook message. He nods, and the next day, on Facebook, he gracefully addresses the MFA question.

***

It’s dark now. AS and I are out on the clean, lit street, looking for a taxi. She flags down one and haggles over a fare in Hausa. She and the driver agree on a price and we get in. As the taxi speeds onto the expressway, AS and I pick up our conversation. We discuss the literary scene. We’re both disappointed about the decision a Nigerian writer recently took. I say that he might not be totally wrong. She cuts in that he is. I agree with her.

We return to talking about publishing in Nigeria. She suggests someone I should speak to about my collection of short stories. I tell her that writing a manuscript is one thing, seeing your name on the jacket of a book is another. That will be a surreal experience I’m not yet sure I have the facility for. It’s much like a performer who’s spent months rehearsing only to develop stage fright on the day of performance. She laughs and tells me to try a pen name.

“No, no,” I say. Maybe when it’s finally a book, everything will settle into place.

She informs me that she once contemplated using a pen name, because the book she’s writing is salacious, and she’s a Northerner and Muslim. She returns to the matter of publishing, maintaining that publishing in Nigeria is best for the authenticity of a work, because a Western editor would likely edit the life out of your book, because it’s a life s/he knows nothing about, or is basically editing to the taste of a Western audience.

By the time the taxi drops me off, my head is buzzing with beautiful images from the event.

***

I get to my apartment, shower and plop into bed. I am too tired, but I cannot sleep. I roll and roll over, thinking about the evening. It occurs to me that I should write an essay about my experience. I discard the thought; I am a fiction writer, I tell myself, not a literary journalist. But I remember one of the writers from the week before—Benson or Ademola—saying that someone once told him that Nigeria writers want to be only just that—writers. They do not want to help out in championing other writers, maybe a stint in publishing or something along that line. Then I remember that Abubakar is also a journalist, and I’ve read many of his interviews of other writers.

The first sentence of the essay comes to me: Abubakar Adam Ibrahim is now a superstar. It will not leave. I decide to write, do something I rarely ever do: write in bed. By the time I’m done, at about 11:26 pm, I turn off my laptop and sleep.

**************

About the Writer:

Ikechukwu Ogbu holds a B.A. in English and Literature from the University of Benin. He lives in Abuja where he’s finished a short story collection and is writing a novel.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions