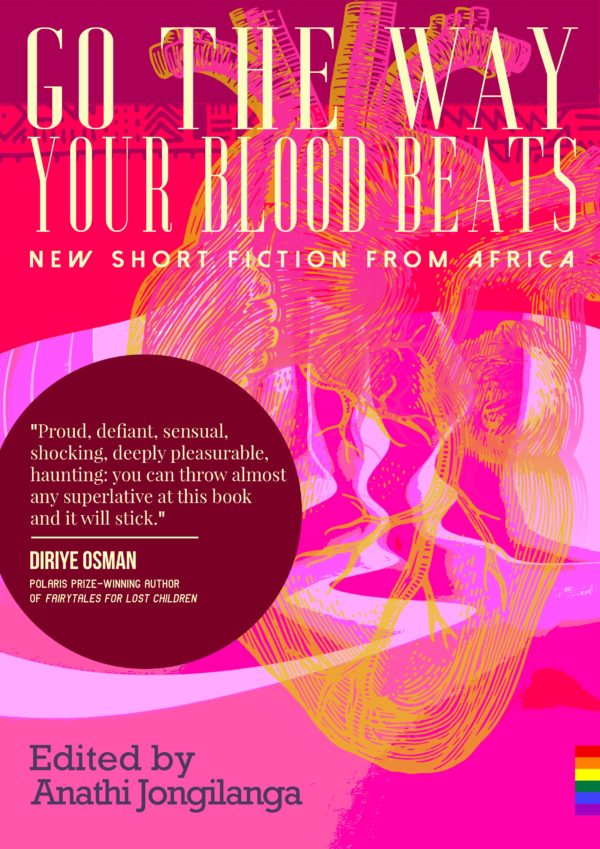

On 8 April, Brittle Paper will publish Go the Way Your Blood Beats: New Short Fiction from Africa, an anthology of twelve short stories exploring queerness in Southern Africa. Edited by the South African writer Anathi Jongilanga, it is introduced by the Somali author & visual artist Diriye Osman.

On 8 April, Brittle Paper will publish Go the Way Your Blood Beats: New Short Fiction from Africa, an anthology of twelve short stories exploring queerness in Southern Africa. Edited by the South African writer Anathi Jongilanga, it is introduced by the Somali author & visual artist Diriye Osman.

__________________________________________________________

THIS IS HOW WE LOVE

In James Baldwin’s seminal 1984 interview with Village Voice journalist Richard Goldstein, he made a series of powerful statements. Baldwin pointed out that ‘the question of human affection, of integrity, in my case, the question of trying to become a writer, are all linked with the question of sexuality. Sexuality is only a part of it. I don’t know even if it’s the most important part. But it’s indispensable.’ When Goldstein pressed Baldwin on what advice he would give to young queer people, Baldwin shared the following wisdom:

Best advice I ever got was an old friend of mine, a black friend, who said you have to go the way your blood beats. If you don’t live the only life you have, you won’t live some other life, you won’t live any life at all. That’s the only advice you can give anybody. And it’s not advice, it’s an observation.

Taking that observation and framing it through a distinctly pan-African lens is what brings us to this deliciously-written and astutely curated anthology of queer African writing in the 21st century. Proud, defiant, sensual, shocking, deeply pleasurable, haunting: you can throw almost any superlative at this book and it will stick. As I read the stories, I fell in love with the collective deployment of language-as-dynamite, the deft pacing of every piece. There is so much ingenuity on display here. Certain stories made my heart burst with sheer pleasure at the possibility and elasticity of the queer African short story in English.

In Acan Innocent Immaculate’s ‘Songbird’, there is an adroitness and sensitivity in the storytelling that would make the most seasoned short story writer puke-green with envy. It’s an intensely poetic piece, laced with mystery. When Zouk is born, her mother is terrified that she is possessed by a powerful magical force. Zouk is mute for the first few years of her life; one day she opens her mouth and sings like her voice is coated in honey. She becomes alluring to all—with damaging consequences.

‘Her Stripes’, by Odah Brian, is a poignant story about a young trans girl who has been forced by her family and community to fold up her identity and keep it hidden away until she realises that such self-denial is a kind of death, and courageously reclaims her life by confronting the demons that have shattered her confidence.

The third story in this exquisite anthology is Vuyelwa Maluleke’s ‘The Thing in the Blood’, in which grief and an indescribable element of alchemy are subtly fused with the desire for a dual acceptance: to be homed within our own bodies, and to find solace and kinship within our families. It’s a moving and elegiac story that heralds the arrival of a fantastic new talent.

‘Ex Vivo’, by Tsholofelo Wesi, is a gorgeously constructed gem with a transgressive, tensile edge. To the Western eye, this story would be construed superficially, as an allegory about incest, suicidal ideations and superstition. But instead it is a story about how we, as queer Africans, are in control of our own mythologies; how brotherly affection can take on a more tender and, dare I say, passionate texture. It also demonstrates how parental disapproval of sexual difference is not necessarily manifested in ways as straightforward as disownment, and that there are complex and nuanced ways to represent who we are and where we are going.

Mercy Wandera’s ‘Cow and Chicken’ is a heart-breaking prose poem about a young girl whose charismatic and adored older brother is punished by his parents for playing around with makeup. An exorcism follows, and this, and the frightened silence of the narrator that accompanies it, makes this story all the more relevant in the face of the often deadly suppression of queerness across the continent—and abroad—through the mediums of supposed spiritual ‘deliverance’ and cruel and scientifically-discredited ‘conversion’ therapies.

In Fiske Serah Nyirongo’s beautiful ‘Who You Are’, our nine-year-old narrator, Lilato, witnesses her aunt Mwangala engaged in an intimate embrace with her female paramour, before her mother, who is Mwangala’s identical twin, quickly breaks up the moment and emotionally blackballs Mwangala from her life. This leaves Lilato without the role model she always looked up to. . . until they reunite sixteen years later in the Netherlands. It’s a short piece, but one where generational traumas are healed, and our sapphic characters find respite from the dehumanising power of a homophobic, heterosexist world that refuses to see them for who they are.

In ‘God in Jeans’, Riley Hlatshwayo conjures a world where his protagonist, Lulama, has intense meetings with Eros in the form of a series of sexually robust but emotionally distant white pretty boys, who either want to consume him or replace romance and tenderness with unbridled, often dehumanizing passion. It’s sexy and enticing, and Hlatshwayo is a writer to watch out for.

These stories are encoded with the sting of melancholy and a genuine sense of hopefulness and regeneration. There is so much to admire about this anthology, and the editor, Anathi Jongilanga, has served up more excitement, passion and moral acuity in these pages than the venerated Western literary magazines currently haemorrhaging readers with their inconsequential narratives of privilege and anomy, manage to do.

Kudos to Brittle Paper for bringing this anthology to the masses. Thank you to Otosirieze Obi-Young for hipping me to this hotness.

So what are you waiting for, reader?

Dig in.

ABOUT THE WRITER

Diriye Osman is a Somali writer and visual artist. He is the author of the short story collection Fairytales for Lost Children (2013), which won the Polaris Award. He can be found at diriyeosman.com.

Diriye Osman is a Somali writer and visual artist. He is the author of the short story collection Fairytales for Lost Children (2013), which won the Polaris Award. He can be found at diriyeosman.com.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions