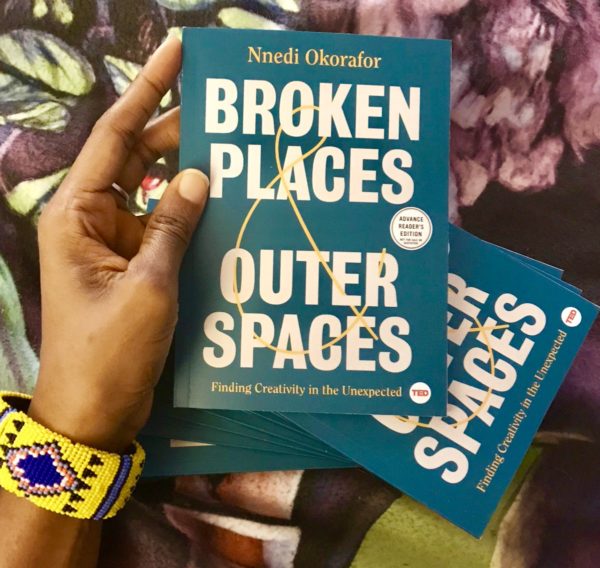

Nnedi Okorafor’s memoir, Broken Places & Outer Spaces: Finding Creativity in the Unexpected, was published on 18 June, by Simon & Schuster imprint TED Books. It is her first book of nonfiction and her 15th book overall in 14 years, since her 2005 debut. In February, on Twitter, she described the 112-page book as a “memoir, science fiction, lots of things,” adding that she had “been writing parts of this book for over two decades.”

The first chapter appears on Simon & Schuster’s website. Read part of it below.

_________________________________________________

1

Beached

The beach was just the way I loved it: empty, its waters comfortable and clear, a few sand crabs dashing around. The air was warm, it was sunny, and the strong wind danced wildly. I had all the time in the world. I stood facing the water, strong but always somewhat unsteady. I had to concentrate more than most on the strength and direction of the wind, focusing my eyes ahead so that I wouldn’t embarrass myself by stumbling. Since the incident two decades ago, I’d been this way.

My toes had to work hard to grasp and feel the sand. The undersides of my feet tingled softly, as if I were eternally walking on a bed of AstroTurf. The area from my ankles to my knees always felt not quite there, vague and elemental. My thighs were strong, the most vibrant part of my legs. My strange curved back was forever pushing me a bit forward. It had been so many years, one would think by now I’d be accustomed to my body feeling this way. But my awareness that I’d once been something else had become an essential part of me—a state of being.

In old age, I won’t be bent over, thanks to my fused spine and the steel rod lashed to it. I can’t wear high heels because of my poor balance. I avoid crowds because standing among many people is like standing in the ocean when the water is whirling around me; I lose my sense of place. When I step onstage in front of large audiences, adrenaline blends with my poor proprioception and this robs me of my balance. The same phenomenon causes me to lose track of my legs while standing.

The wind blew against my back and I stumbled forward. Toward the water. Still, I didn’t go in.

There’s a strange feeling that I experience before I can go into the ocean. It happens at the point just before the ability to walk stops mattering and the ability to swim begins to matter. This is especially true when it’s windy, motion not only in the water, but also in the air. The hypnotic ripples on the surface of the water, the swirling of the air, and the sinking and suction of the sand beneath my feet take my balance away. Before I can get to the point where I am swimming, I have to fall.

I stood there in the nourishing sunshine, thinking about my legs and science fiction. I had recently written about a superheroine for Marvel, a wheelchair-bound girl in Nigeria named Ngozi. She physically and mentally bonds with an alien symbiotic organism named Venom and is thus able to stand up and kick ass. Ngozi made me consider my own proprioceptively challenged body, how it could be augmented with technology and allow me to move about the world with ease and agility. Not as I used to in the first half of my life, but as a cyborg.

My legs would be caged with an exoskeletal machine made of a fine webwork of magnesium alloy. My gait would be so well augmented that I’d be able to leap, run, even cartwheel better than I ever could before it all happened. My spine would be replaced with a strong yet flexible organic substance that would allow me to turn my head all the way around like an owl, support my body, and allow me to do epic backbends. With the steel in my back, I already identified as a rudimentary cyborg, part basic machine, so it wouldn’t be that much of a leap.

Before the incident, I moved about the world with a sense of ease and entitlement. I was the kid in gym class who everyone always chose first for their team because I was the fastest, could jump the highest, could throw the farthest and hardest, could aim the most accurately. To myself, I was the athlete and the budding scientist. Then quite suddenly everything changed, and I was an athlete drifting in the vacuum of space and I’d lost faith in the sciences.

Before the incident, I was sure I’d be an entomologist. Since I could remember I’d loved and been fascinated by insects, especially those in the orders of Lepidoptera and Orthoptera, butterflies, moths, grasshoppers, and crickets. Praying mantises, too. Creatures with strong legs and unique wings.

In second grade, I built a giant butterfly out of various colors of construction paper. Then I sat on it and waited. And waited. And waited. When the butterfly didn’t come to life, happily greet me, and then fly me into the sky, I was depressed for the rest of the day.

I was an imaginative child. Pop-up books were portals to other planets and dimensions, even if they were nonfiction books about human anatomy or the world of birds. I read the Moomin books by Tove Jansson and my imagination exploded even more. As a teen, I consumed horror and fantasy novels as if they were nonfiction. For me, the dark has never been uninhabited. The wind has always brought things. Masquerades are real and the ancestors can be guides.

However, though I’d always loved the sciences, I wasn’t born with an interest in science fiction. My journey to writing science fiction did not start with reading it. I didn’t discover authors like Octavia Butler and Ursula K. Le Guin until I was already writing about strange planets and advanced societies that use flora-based biotech. And I read Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein as an annoying book assigned to me in my high school English class.

Growing up, most science fiction novels and films presented boldly white male-dominated worlds where I knew I could never exist on my own terms. In these narratives, I found that I, more often than not, empathized with the aliens/others more than the protagonists, so reading these stories felt more like an attack on my person than an empowerment. I also resisted the themes of exploration with the intent to colonize that ran so strong in these narratives. They never felt right to me (especially being the child of immigrants from an African country colonized by Europeans) or interesting.

Ultimately, I lost my faith in science after an operation left me mysteriously paralyzed from the waist down. It took years, but battling through my paralysis was the very thing that ignited my passion for storytelling and the transformative power of the imagination. And returning to Nigeria brought me back around to the sciences through science fiction, for those family trips to Nigeria were where and why I started wondering and then dreaming about the effects of technology and where it could take us in the future.

This series of openings and awakenings led me to a profound realization: What we perceive as limitations have the potential to become strengths greater than what we had when we were “normal” or unbroken.

_____________________________________________________

Continue reading on Simon & Schuster’s website.

Let’s Rewind: June 2019 | Zezee with Books June 29, 2019 10:29

[…] Read Chapter One of Nnedi Okorafor’s New Memoir, Broken Places & Outer Spaces: Finding Creativ… (brittlepaper.com) […]