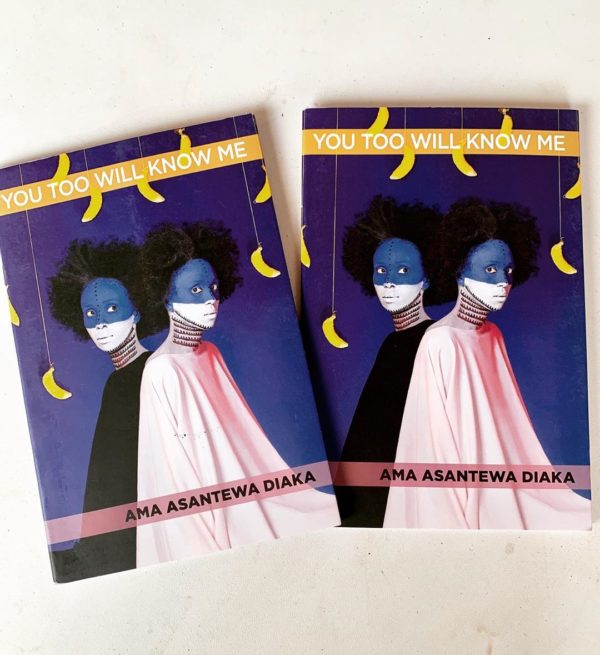

Publisher: Akashic Books. As part of African Poetry Book Fund (APBF)’s New-Generation African Poets: A Chapbook Box Set (Sita), edited by Kwame Dawes and Chris Abani.

Publication Date: 11 June 2019.

*

In You Too Will Know Me, the debut chapbook by the Ghanaian poet Ama Asantewa Diaka, life is a paradoxical tightrope and she is a begrudging acrobat. Begrudging, because while she executes with finesse, it is the cost of her tightrope walking—”body sagging under the weight of reality” as she records in “Shameplant”—that complicates the precarity of her walk.

The poems manifest as multiples of sometimes related dualities. To begin this tour of paradoxes, Diaka harnesses biblical allusion to offer us a reimagining of what could be from what already is. In “Paul’s Whole Verse,” the opening poem, Diaka reinterprets a conclusive fraction of the Apostle Paul’s epistle in Philippians 4:8 as an entry point into how things can mean what we want them to mean. Where Paul writes a prescriptive epistle for the church, Diaka writes a declarative billet-doux for an audience she invokes before this poem begins. She makes a congregation of us, charging us to be receptive to her “eagle-winged” reimagining of pre-existing understanding. Here, Paul’s “brethren” become Diaka’s “lover born on a Thursday”; Paul’s “whatever things are true” is equal to “pain that measures on a scale of 9.7”; “whatever things are noble” begin with “Ghana jollof”; and “whatever things are just,” according to Diaka, are “orgasms that make your legs twitch.” She speaks to us by speaking to the Apostle Paul, invoking him only to supplant him.

From God and Paul to lovers and the congregation of us, Diaka works through her themes by employing apostrophe. Staying true to her tradition of balancing the sacred and the not-so-sacred, she alludes to Jesus Christ’s Passover feast (most likely as quoted by Apostle Paul in I Cor. 11:24) in the title of the poem, “Take, Eat.” As she once again supplants the biblical to serve the physical, her address shifts from the religiously sacred God to the culturally sacred elder (mother/father of a lover in this case). The poem begins, “I have left parts of myself on your son’s body,” and continues, “I have tasted him.” The complexity of this poem emanates from the way it works with and within multiple tools and themes of duality. Combining biblical allusion and apostrophe enables her to continue her navigation of the piety-profanity duality, while introducing another thematic duality in consumption and expulsion. Like Jesus, the “Son” whose body is broken and offered to those he loves to “take, eat,” the persona “takes” and “eats” the body of another son who breaks his body for her as a token of his love.

When she engages apostrophic address in “Spurting,” as she is “waiting for” a present but absent lover “to give her reason,” she allows us a grip of the now familiar, so she can usher in the new. Unlike previous ones, this poem is built through couplets, both formal (closed) and run-on (open). With this poet, what is new is only a reimagining of what has been, and her use of corporeal diction in this poem appears new because she eases us into it through strategically scattered intimations. A dynamic poetics of the corporeal where the body and bodily imagery is called upon as witness, is growing as a region within the ocean of contemporary poetry. In these waters Diaka (re)baptizes us, as she names the body and returns to it without fail. In “Spurting” alone she gives us “the nook” of her “collarbone,” her “leg between” her absent lover’s “butt cheeks,” her “eyes closed,” her grandmother’s “green thumb” in her “bones” and concludes the poem by telling us that “. . . all this body knows how to do is to flare.” And why wouldn’t it flare when it is expected to “be ridiculously multifaceted,” like Diaka informs us in her longest titled poem of the collection, “And I’ve Mastered the Art of Receiving Handouts because I Come from This Place.”

Being “ridiculously multifaceted” haunts her, sometimes even in her language, by muddling the consistency of her metaphors which in turn upsets the crispness of her imagery. In “Bulky Building,” for example, lovers are “stemmed from branches” while romance “bleeds” or “gets rusty” or “croons like a faulty car engine.” The jump in imagery, from blood to rust to sound, threatens the sanctity of her narrative. Indeed, this poem wobbles the most on a tightrope among the rest in this collection.

But Diaka is more than capable of contorting into shapes that we recognize with magnificent clarity. Shapes like love-hate relationships and experiences. Mistress of balancing acts that she is, Diaka does not retreat from confronting love’s many other forms. In “Forgiveness,” she writes, “You plough the road of failing friendships / where awkwardness is an easy language,” speaking of the hardness of platonic love. But in “Shameplant,” she represents amorous love by making surprising beauty from what would otherwise be trite tenderness. Of her lover the persona says, “The moon learnt how to arc its back / from studying the perfect shape of your eyes.”

Perhaps it is in “Bloom,” where she constructs a clear mosaic of her love-hate relationship with Ghana by relying on apposition and similes, that her skill blossoms the most. The streets of Labadi come alive: “I can tell from the way the dark-skinned woman with the y-shaped scar / on her left leg / scrubs her baby, that she is a woman who believes in redemption.” In the next lines, she dives with even deeper clarity into her scene, “Two boys are moving like they’ve got too much rhythm in their bodies / and not enough time to dance it out.” She concludes the stanza thus, “On the pavement, a porridge seller is giving out smiles / like they are Amens to needy requests.” Not one to leave the congregation astray, Diaka simply informs, “These people teach me / that if you are from Accra and you are placed anywhere in / the world, / there’s no way you won’t know how to bloom.”

In You Too Will Know Me, we see majestic finesse. Diaka makes us know. And we, like the wonders she balances, come to recognize her as a capable bearer of life’s intriguing dualities and complexities.

BUY Ama Asantewa Diaka’s You Too Will Know Me

About the Reviewer

Nana Prempeh’s work appears in Africa Is a Country and elsewhere. Longlisted for the 2018 Koffi Addo Prize in Creative Nonfiction, he is currently a graduate fellow and graduate teaching associate in the English Department of Chapman University.

Nana Prempeh’s work appears in Africa Is a Country and elsewhere. Longlisted for the 2018 Koffi Addo Prize in Creative Nonfiction, he is currently a graduate fellow and graduate teaching associate in the English Department of Chapman University.

My Thoughts: Woman, Eat Me Whole – The Spider Kid's Blog July 20, 2022 05:24

[…] Diaka’s second book of poetry, following (and including some poems from) her APBF chapbook, You Too Will Know Me. The book is organized in four sections, each named after one word in the book’s title. Indeed, […]