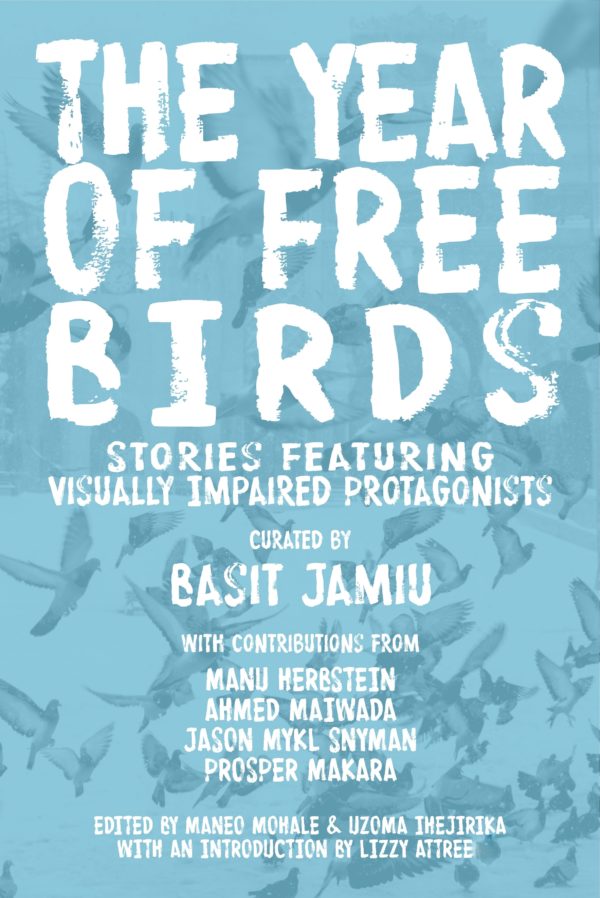

In October 2019, Brittle Paper will be publishing The Year of Free Birds: Stories Featuring Visually Impaired Protagonists, the second release in the Afro Anthology Series, curated by the Nigerian writer Basit Jamiu. Edited by South Africa’s Maneo Mohale and Nigeria’s Uzoma Ihejirika, contributors to it include Manu Herbstein, Ahmed Maiwada, Jason Mykl Snyman, and Prosper Makara. This will be our 12th e-anthology publication. Here is the Introduction, by former Caine Prize director and Short Story Day Africa board member Lizzy Attree.

*

Those of us reading these words on an electronic screen have the privilege of sight. We can see. We can read with our eyes. In our increasingly LCD-centred worlds, the rise of visual power in our virtual universes on smart phones and on social media has led to a proliferation of iconophilia that must be unprecedented in human history. One benefit for lovers of letters is that the image+text-based nature of the Internet means that reading and writing, albeit in shorter and shorter bursts, have risen alongside the hacking of our brains by ‘free’ apps and advertising. Rates of literacy in Africa are often foregrounded and contested when African literature is championed or discussed, and yet rarely mentioned in such debates are the continent’s over five million blind citizens, whose ability to read is secondary to their inability to see anything at all—with their eyes at least. And yet the World Health Organisation (WHO) notes:

[A]pproximately 26.3 million people in the African Region have a form of visual impairment. Of these, 20.4 million have low vision and 5.9 million are estimated to be blind. It is estimated that 15.3% of the world’s blind population reside in Africa.

So where can we find their stories? Who is writing them? And are they written or read by the blind themselves? Those reading using braille are using touch to detect, translate and understand the words in stories. Those hearing stories read or spoken aloud rely on their aural skills to imbibe and pick up meaning, detecting registers and intonations that are perhaps lost on other readers. The gift of sight is but one of humanity’s five senses, and yet the absence or loss of sight is often considered one of the most life-shattering experiences a person can endure. But life doesn’t end with blindness (indeed it can begin in that state). Life continues, altered, transformed, reconceived.

In order to challenge stereotypes of blindness, in 2018 a call for submissions was made for short stories by African writers centred around visually challenged protagonists, or that has visual impairment as its core theme. From a pool of 87 submissions, four stories were selected to form this anthology, curated by Basit Jamiu, as the second publication in the Afro Anthology Series, and edited by Maneo Mohale and Uzoma Ihejirika.

The four contributors—Manu Herbstein (Ghana), Prosper Makara (Zimbabwe), Ahmed Maiwada (Nigeria), and Jason Mykl Snyman (South Africa)—have all written intriguing responses. They focus on completely blind protagonists whose lifespans include: gambling with longevity, in “The Centennial Game”; avenging and reclaiming slave history, in “Ama”; battling with false prophets, in “Apple, Again”; and facing Murambatsvina, in “The Woes of Hatcliffe Extension.”

In “The Centennial Game,” Snyman’s description of Abidan Cointe’s world in the Hodegetria Gardens, “built for the perfumes and textures and. . . tastes” rather than for the visual beauty of plants and flowers, are evocative and sensual, deftly drawing the reader into a consciousness where eyesight is no longer essential. Referencing Dylan Thomas, Terry Pratchett and Ingmar Bergman, Snyman’s cleverly constructed confrontation with mortality shows the eternal battle between life and death with wit and compassion.

In contrast, Ahmed Maiwada’s “Apple, Again” clearly sets visual impairment alongside mental delusions and/or intellectual blindness. Suspicion and anger grow in the darkness between a cynical retired thief and his wife of twenty years whose movements and perfume suggest betrayal to her bitter, housebound spouse. Amusing plays on the dialectical nuances of Kano Hausa and Zaria Hausa rub alongside comic gems describing “the Naira [wife] that he knew and the honey badger were one and the same animals, uncaring.” And the surprisingly sinister: he knew her body, “it was quite warm to the touch, like newly passed urine that was sealed in a nylon bag.” Confounding expectation in the final twist of the story, Maiwada leaves the reader unclear whether the invisible world does exist after all.

In “The Woes of Hatcliffe Extension,” Prosper Makara’s central character Raviro imagines and hears a great deal as she walks through Harare clutching a prescription she cannot afford from her doctor, so that it is not until the second page that the reader realises she is completely blind. The reminders of the dire poverty of the northern suburbs, which was compounded by the destruction of houses and shacks in 2005 as ordered by Robert Mugabe, would be shocking if conditions in Zimbabwe were any better today. Makara succeeds in conveying the tragedy of preventable blindness, describing Raviro’s cataracts as “slight milky cloudiness” that slowly became “fully blank vision”—purely as a result of marital abuse and neglect and, crucially, of lack of money for a desperately needed “medical redemption.”

Manu Herbstein received the 2002 Commonwealth Writers’ Prize for Best First Book for his searing first novel Ama, A Story of the Atlantic Slave Trade (2000), and he submitted extracts both from it and from his Brave Music of a Distant Drum (2012). Both novels focus on the blind Ama, whose right eye was taken out by “Knagg’s whip.” The excerpted sections form an abbreviated taste of Ama’s story which she explains has to be told because it “lies within me, kicking like a child in the womb, a child whose time has come.” It is a great privilege to be able to include Herbstein’s writing in this collection, these short extracts powerfully illuminate the horrors and complexities of African slavery, such that Ama is not portrayed as the only character that is blind—not when humans could be blind to each other’s humanity.

In Sophocles’ Antigone, as well as in other Greek literature, Teiresias is a prophet, sent by the gods to reveal truth to those who will hear him. Ironically, this prophet, or seer, is literally blind, though he is able to figuratively “see” the truth as well as the future. Achebe also used blindness as a metaphor for wisdom when he said that “The story is our escort, without it we are blind.” We need stories to understand the past, decipher the present and prepare for the future. As Stevie Wonder once said, “Just because a man lacks the use of his eyes doesn’t mean he lacks vision.”

I always urge readers to listen for silences, to look for gaps in representation, to read carefully and critically. I hope that this stimulating, original anthology will encourage readers and writers alike to consider visual impairment more thoughtfully, so that it does not simply function as a plot device, a routine draconian punishment, a blessing or a curse, or an impossible disability, but as an opportunity to consider the world differently.

About Lizzy Attree:

Dr. Lizzy Attree is the co-founder of the Mabati-Cornell Kiswahili Prize for African Literature. She has a PhD from SOAS, University of London. Blood on the Page, her collection of interviews with the first African writers to write about HIV and AIDS from Zimbabwe and South Africa, was published by Cambridge Scholars Publishing in 2010. She is a Director on the board of Short Story Day Africa and was the Director of the Caine Prize from 2014 to 2018. She was part of the founding board of Writivism, which is part of the Centre for African Cultural Excellence (CACE). She taught African literature at Kings College London, has taught at Goldsmiths College, and will teach World Literature at Richmond, London this autumn. In 2018, she completed an Arts Council-funded project on African footballers at Chelsea and Arsenal. She has published the associated anthology of poems Thinking Outside the Penalty Box with the Poetry Society. She is an honorary research associate in the Department of Literary Studies in English, Rhodes University.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions