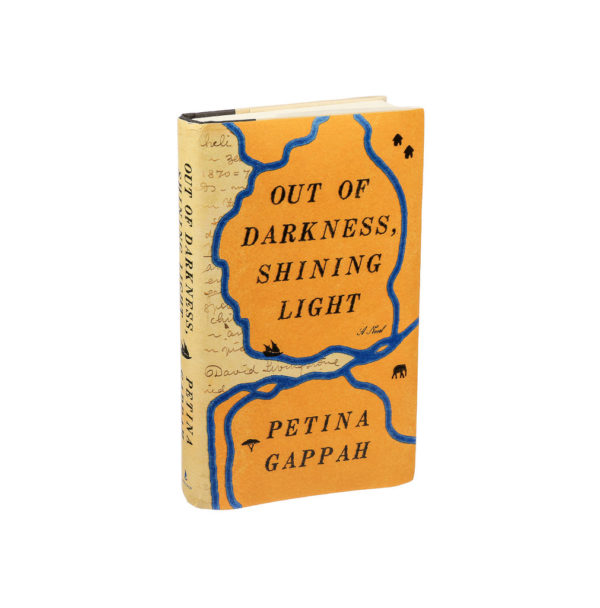

Petina Gappah‘s new novel Out of Darkness, Shining Light was released on 10 September by Simon & Schuster imprint Scribner. Told by a woman and a man, it details the 285-day journey by a party carrying the Irish explorer Dr. David Livingstone’s dead body to the Indian Ocean coast. The publication of the highly anticipated book, the Zimbabwean author’s fourth, was preceded by a profile of her in The New York Times. The first excerpt from it is now available, from Literary Hub.

The lawyer, who revealed last year that the book would be the first in her Rhodesia Trilogy, is the author of the Guardian Best First Book Award-winning story collection An Elegy for Easterly (2009), the Women’s Prize-nominated novel The Book of Memory (2015), and another story collection Rotten Row (2016)—three which she regards as her Zimbabwe Trilogy. Named the Brittle Paper African Literary Person of the Year in 2016, her short story, “The News of Her Death,” was included in Sunday Times‘ 2018 list of “The 100 Best Short Stories of All Time.”

OUT OF DARKNESS, SHINING LIGHT: EXCERPT

It is strange, is it not, how the things you know will happen do not ever happen the way you think they will happen when they do happen? On the morning that we found him, I was woken by a dream of cloves. The familiar, sweetly cloying smell came so sharply to my nose that I might have been back at the spice market in Zanzibar, a slim-limbed girl again, supposedly learning how to pick out the best for the Liwali’s kitchen, but really standing first on one leg, then the other, and my mother saying, but, Halima, you don’t listen, which was true enough because I was paying more attention to the sounds of the day—the call of the muezzin, the cries of the auctioneers at the slave market, the donkeys braying in protest, the packs of dogs snarling over the corpses of slaves outside the customs house, and the screeching laughter of children.

I think of my mother often enough, but it is seldom that she comes to me in my dreams. She was the suria of the Liwali of Zanzibar, one of his favorite slaves, although she never bore him a child to become umm al-walad, and what a thing that would have been for her, to bear the Liwali’s child; for he was the Sultan’s representative back in the days when Said the Great, Seyyid Said bin Sultan that was, lived in Muscat, across the water in Oman, and not in Zanzibar.

My mother says I was born before the Sultan moved the capital from Muscat. In those days, the Sultan had the Liwali to act for him in Zanzibar, and yes, there was the great lord of the Swahili in Zanzibar, the Mwinyi Mkuu, they called him, but the Sultan needed his own man, someone who was an Arab through and through, an Omani of the first rank.

Though to look at the Liwali, well, you could see at once there was an African slave or two in his blood, and that’s no lie. He had his three official wives, the Liwali did, he had his three horme, they called them, and also his concubines, the ten sariri in his harem. That is plenty enough woman for any man, but it was not nearly as many concubines as Said the Great, for he had 75 wives and sariri, who gave him more than 100 children.

My mother was the only dark-skinned suria among the Liwali’s sariri concubines, for they were all Circassians and Turks and whatnot, and although they said a suria was the best kind of slave to be, and only the comely women were chosen to be sariri, for my mother, who was also a cook, being a suria only meant that she was doubly enslaved: at night, a slave in the Liwali’s harem, and in the day, a slave in his kitchen.

The Liwali has been dead these many years. His house is now owned by Ludda Dhamji, a rich Indian merchant from Bombay. They say he is more powerful than the Liwali was, for he has lent Said Bhargash, the new sultan, ever so much money. Ludda Dhamji controls the customs house too, and takes a share of every slave sold at the slave market and every single one that goes to Persia and Arabia, to India and up and down the whole coast of the Indian Ocean. That is wealth indeed.

I was roused from my dream, and all thoughts of my former life, by the sound of running feet and loud voices. I could tell at once that something was wrong. Ntaoéka and Laede had not yet made the fires, no surprise that, for it was between the morn and night. For all that, I could make out their forms easily enough; the moon was still bright. The watch was up, but so were others who need not have been. The porters and expedition leaders were in a flurry of movement. Even the most useless of the pagazi, like that thief Chirango, who normally needed Majwara’s drum to beat some spirit into his lazy legs, moved as quickly as the others, going from one group to the next, and then from that group to the one after that.

Susi ran to the boy Majwara, Asmani ran to Uledi Munyasere, Saféné ran to Chowpereh. It was all confusion, like chickens before a rainstorm. Under the big mvula tree, the Nassick boys were conferring in a huddle.

There were seven of them, all freedmen who had been captured by slavers as boys and rescued by giant jahazi sent by the queen from the land of Bwana Daudi. Ships, they called them, dhows that are as high as houses and almost as big as the Liwali’s palace, Susi said. They had been taken in these jahazi ships to India, where they were taught to speak out of their own tongues, and instead learned all sorts of other muzungu tongues to speak. They were also given trades to learn and books to read, and paper to write on and clothes that made them look like wazungu.

Continue reading on Lit Hub.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions