The 5 Shortlists for The 2019 Brittle Paper Awards were announced in November. Begun in 2017 to mark our seventh anniversary, the Awards aim to recognize the finest, original pieces of writing by Africans published online.

READ: The 2017 Brittle Paper Award for Essays & Think Pieces: Meet the Finalists

READ: The 2018 Brittle Paper Award for Essays & Think Pieces: Meet the 7 Finalists

The $1,100 prize is split across five categories: The Brittle Paper Award for Fiction ($200), The Brittle Paper Award for Poetry ($200), The Brittle Paper Award for Creative Nonfiction ($200), The Brittle Paper Award for Essays & Think Pieces ($200), and The Brittle Paper Anniversary Award ($300), for writing published on our site. The winners will be announced on or after Tuesday, 10 December 2019.

Meet the Finalists for the 2019 Brittle Paper Award for Essays & Think Pieces

MAAZA MENGISTE (Ethiopia), for “Writing About the Forgotten Black Women of the Italo-Ethiopian War,” in Literary Hub

Maaza Mengiste is a novelist and essayist. She is the author of the novels: Beneath the Lion’s Gaze, selected by the Guardian as one of the 10 best contemporary African books; and The Shadow King, called “a brilliant novel. . . compulsively readable” by Salman Rushdie. She is the recipient of fellowships from the Fulbright Scholar Program, the National Endowment for the Arts, and Creative Capital. Her work can be found in The New Yorker, The New York Review of Books, Granta, The Guardian, The New York Times, Rolling Stone, and BBC, among other places. Maaza’s fiction and nonfiction examine the individual lives at stake during migration, war, and exile, and consider the intersections of photography, memory, and violence. She was a writer on the documentary projects, GIRL RISING and THE INVISIBLE CITY: KAKUMA.

FROM “Writing About the Forgotten Black Women of the Italo-Ethiopian War”:

While developing Hirut’s narrative, I read the stories of female soldiers from across the centuries. From Artemisia of Caria in 480BC to the women in the army of the Kingdom of Dahomey in early 18th century Benin, to the more recent Yazidi women’s army that fought against ISIS, I have come to realize that the history of women in war has often been contested because the bodies of women have also been battlefields on which distorted ideas of manhood were made. If war makes a man out of you, then what does it mean to fight beside—or lose to—a female soldier? For centuries, women have been providing their own answers to this. But history—that shape-shifting collection of memories and data replete with gaps—would want us to believe that every female soldier plucked out of oblivion and brought to light is the first and only one. But that has never been true, and it is not true now.

NAMWALI SERPELL (Zambia), for “On Black Difficulty: Toni Morrison and the Thrill of Imperiousness,” in Slate

Namwali Serpell is a Zambian writer who teaches at the University of California, Berkeley. She won the 2015 Caine Prize for African Writing. She received a Rona Jaffe Foundation Writers’ Award for women writers in 2011 and was selected for the Africa39, a 2014 Hay Festival project to identify the best African writers under 40. The Old Drift (Hogarth/PRH, 2019) is her first novel and has been long listed for the Center for Fiction First Novel Prize. She was shortlisted for the 2017 Brittle Paper Award for Fiction, for “Triptych: Texas Pool Party.”

FROM “On Black Difficulty: Toni Morrison and the Thrill of Imperiousness”:

Morrison’s democratic bent doesn’t pander, however. She doesn’t condescend to your level but challenges you to rise to hers: “My writing expects, demands participatory reading.” As she’s said of Faulkner: “The structure is the argument.”

Morrison herself might reject this comparison. “I am not like James Joyce; I am not like Thomas Hardy; I am not like Faulkner,” she has said. “I am not like in that sense.” If this seems unduly pointed, she shuns comparison with Maya Angelou and Alice Walker, too: “They’re very different writers, very, very different from me.” How? “Well, one self-edits and one doesn’t.” This is, I think, the source of Morrison’s reputation as a difficult personality. On one hand, she refuses to be whitewashed into canonical neutrality. On the other, she refuses to be relegated to her race or gender, not because black womanhood is less than, but because it is often condemned to a narrowness disavowed by other identities. “I’m already discredited, I’m already politicized, before I get out of the gate.”

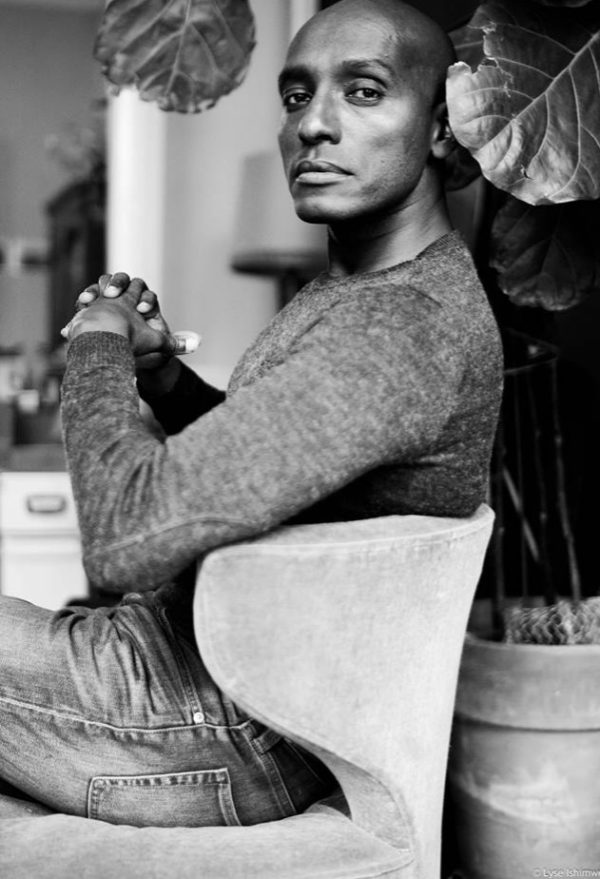

SULAIMAN ADDONIA (Eritrea/Ethiopia/UK), for “Writing Like Degas Paints,” in Granta

Sulaiman Addonia is an Eritrean-Ethiopian-British novelist. His first novel, The Consequences of Love, shortlisted for the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize, was translated into more than 20 languages. Silence is My Mother Tongue, his second novel, has been longlisted for the 2019 Orwell Prize for Political Fiction. He currently lives in Brussels where he has launched a creative writing academy for refugees and asylum seekers & the Asmara-Addis Literary Festival (In Exile).

FROM “Writing Like Degas Paints”:

I remember the day I stood in front of a mirror naked after a dance. I opened my body to my own inquisitive stare. I wasn’t looking at the massacre I had survived as a two-year old boy, the years I spent in a remote camp, and those that followed in Saudi Arabia. My image of myself now wasn’t disturbed by the challenges I had faced in London. I was looking at this half-Eritrean, half-Ethiopian man still standing, still dancing. Nudity enabled me to see me and not all that surrounded me. As I looked at the pictures I had taken of myself in different poses, unclothed by fabric or history, I began to discover things buried deep inside me: the woman in me as well as the man, the immigrant, the wanderer, the silent boy, the stubborn, flawed human being that I am. I was more than a refugee. I was one hundred other things too.

ORIS AIGBOKHAEVBOLO (Nigeria), for “Trauma and a Victim Complex in Nigerian Writing,” in Brittle Paper

Oris Aigbokhaevbolo holds a Doctor of Pharmacy degree and has worked for about a decade as a writer, journalist, critic and communications personnel. He is the founder of the Society of

Culture Critics. He won the Journalist of the Year award at the 2015 All Africa Music Awards (AFRIMA). He has attended the critic academies in South Africa, Germany, and the Netherlands, becoming the first writer to be invited to all three programmes in a single year. He has also mentored film critics at the Durban International Film Festival and received an award from the Felabration Festival for his editing and curating of music writing on Fela Anikulapo Kuti.

In 2017, he was the African writer-in-residence at the island of Sylt in Germany. To improve Nigerian writing and business communication, he began the Write With Style Workshop in 2018 and established the communications outfit Critics & Bylines this year.

Aigbokhaevbolo’s work has appeared in The Guardian UK, Chimurenga, and The Africa Report. His nonfiction writing has received three consecutive nominations at the annual Brittle Paper

Awards. He is the author of the forthcoming collection of nonfiction, From Chimamanda to Wizkid: Essays and Reviews on Nigerian Pop Culture.

FROM “Trauma and a Victim Complex in Nigerian Writing”:

This produces a political problem. We are forced to think in movements because we have been othered. The West might produce stories and writers of vastly different concerns in any given generation, within longlists, within shortlists, within prize-winners’ lists, but successful Nigerian writers and Nigerian writing are commonly and easily grouped. To simplify and elide overlapping themes here and there: first came those against the erosion of traditions by the white man; then those against military dictatorship; then the poverty porn purveyors; then the immigrant story group. The nonfiction boom it appears we are in the middle of is characterised by an individual narrative punctuated with trauma. As with the Caine Prize highlighting stories that later got grouped and called poverty porn, Catapult’s publishing of stories featuring Nigerian trauma gave birth to similar stories.

PANASHE CHIGUMADZI (Zimbabwe/South Africa), for “Why I’m No Longer Talking to Nigerians About Race,” in Africa Is a Country

Panashe Chigumadzi was born in Zimbabwe and raised in South Africa. Her debut novel, Sweet Medicine (Blackbird Books, 2015), won the 2016 K. Sello Duiker Literary Award. She is the founding editor of Vanguard magazine. A columnist for The New York Times and contributing editor to The Johannesburg Review of Books, her work has featured in titles including The Guardian, Chimurenga, The Washington Post, and Die Ziet. Her second book, These Bones Will Rise Again, a reflection on Robert Mugabe’s ouster, was published in June 2018 by The Indigo Press. Her essay, “History Through the Body or Rights of Desire, Rights of Conquest,” won the 2018 Brittle Paper Award for Essays & Think Pieces. She is a doctoral candidate at Harvard University’s Department of African and African American Studies.

FROM “Why I’m No Longer Talking to Nigerians About Race”:

Having suffered many South African queues in my lifetime, I can almost certainly guarantee that if a black South African manager had decided to defend their dignity, they would do so by first declaring that they are a proud black person and on that basis would not allow themselves to be treated by a white man in this way. The ordeal might have lasted longer, drawn in more people and unlikely have ended with the white man expressing his gratitude for the black man’s graciousness. While it is true that the manager’s booming voice and imposing physical stature already gave him an unfair advantage, I can say almost certainly that it was his Nigerian “Tigritude” that allowed him to summarily dismiss the white man’s temper tantrum, not necessarily because he was a racist oyinbo (which he almost certainly was), but simply because he was a client with bad home training behaving badly in his house. Negritude? Tigritude!

I will never repeat these words anywhere else, but let it be said here: sometimes it is only Nigerian arrogance that can successfully stare down white racial arrogance.

Enquiries, about the shortlisted writers or for interviews with them, can be sent to [email protected].

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions