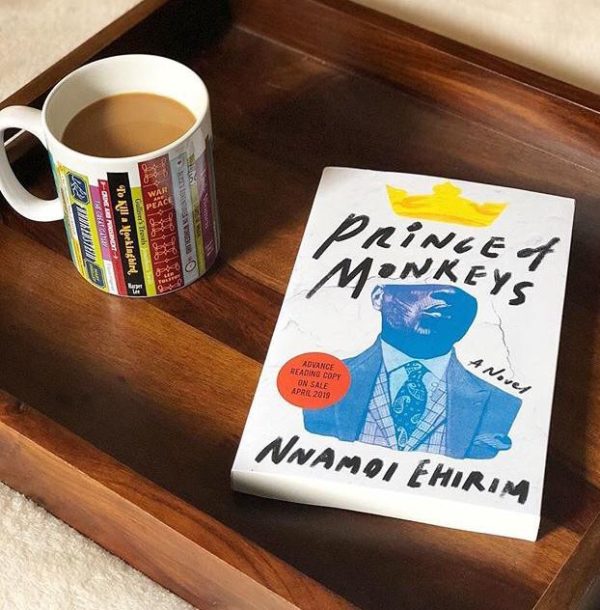

The Nigerian novelist Nnamdi Ehirim’s debut, Prince of Monkeys, was published by Counterpoint Press exactly a year ago, on 2 April 2019. Set in the late 1980s to early 1990s, it follows a group of pop culture-and-politics-aware friends whose lives are upended after an anti-government riot and who go on to chart different paths. The novel, most recently longlisted for the 2020 VCU Cabell First Novel Award, was named one of Brittle Paper‘s Top 15 Debut Books of 2019.

Here is a synopsis:

Growing up in middle-class Lagos, Nigeria during the late 1980s and early 1990s, Ihechi forms a band of close friends discovering Lagos together as teenagers with differing opinions of everything from film to football, Fela Kuti to spirituality, sex to politics. They remain close-knit until tragedy unfolds during an anti-government riot.

Exiled from Lagos by his concerned mother, Ihechi moves in with his uncle’s family, where he struggles to find himself outside his former circle of friends. Ihechi eventually finds success by leveraging his connection with a notorious prostitution linchpin and political heavyweight, earning favor among the ruling elite.

But just as Ihechi is about to make his final ascent into the elite political class, he reunites with his childhood friends and experiences a crisis of conscience that forces him to question his world, his motives, and whom he should become. Nnamdi Ehirim’s debut novel, Prince of Monkeys, is a lyrical, meditative observation of Nigerian life, religion, and politics at the end of the twentieth century.

Prince of Monkeys earned positive pre-publication reviews. Publishers Weekly described it as an “incisive debut. . . a vivid, astute portrait of Nigeria—and its people—in the throes of upheaval.” Kirkus Reviews praised its “beautifully evocative prose” and called it “a panoramic novel showing that the price of growing beyond one’s origins might be steeper than anticipated.” Booklist gave it a starred review, calling it “remarkable . . . eloquently succeeds in driving home the steep costs of complacency.”

A month after its release, The New York Times Book Review came calling. “Nnamdi Ehirim’s first novel shows us a Nigeria that exists in both fantastic and tragic terms,” the American journalist Tre Johnson wrote in his review. “As Ihechi climbs the ranks of society toward financial freedom, he paradoxically finds later in the novel that, as he wrestles with a past he seeks to make peace with, its collisions with his present and future feel as calamitous as the riots. . . . Ihechi finds himself involved in another moment of upheaval, one that proves he can be transformed yet again.” In Arts and Africa, the Nigerian writer Amatesiro Dore called it “the memoir of a generation, with the corrupt voice of Nigerian millennials documenting the failures of our elders and betrayal of our nation.”

Ehirim, who is still 26, is based in Lagos and Madrid. He cofounded a clean-energy start-up in Nigeria and is currently pursuing an MBA focused on entrepreneurship in the renewable energy sector. His writing has appeared in Afreada, Catapult, The Kalahari Review, The Republic, and here on Brittle Paper. Last year, his essay, “How a New Generation of Nigerian Writers Is Salvaging Tradition from Colonial Erasure,” appeared in Literary Hub. Prince of Monkeys was named one of Channels TV’s “Top Nigerian Books of 2019.” Ehirim was listed by YNaija as one of the “Revelations of the Year.”

In an interview with Inside Hook, Ehirim talked about the beginnings of the novel, how he was inspired by his favourite musicians to start it. “I realized every artist on [my] playlist was about my age; Isaiah Rashad, Chance the Rapper, SZA,” he said. “This was 2014 and neither of them were exactly superstars yet, but they were all young folks creating the art they wanted to create and finding an audience halfway across the world. So I figured I could do the same.

“What is now the prologue of the novel was a short story I had submitted for the Commonwealth Short Story Prize. I had also submitted it to Granta and The New Yorker, all to no avail. It was much too lengthy to get published in Brittle Paper or Saraba and I was 100 percent sure I didn’t want it trimmed. So I built on it and made it into a novel and then my editor eventually still had it trimmed.”

He elaborates on his progression in an interview with Arts and Africa. “It also covers themes that are very personal to me because, primarily, I wrote it for myself; friendship, art in all forms, politics, spirituality. I hadn’t published even a short story as at the time I started. My readership was my mailing list. So there was no burden or pressure of writing something ‘publishable’ because that was more of a dream than an ambition. But that allowed me to be carefree. To discuss whatever theme in whatever voice I desired, to be more experimental with humour and use of language. And in writing it, after the part one, I knew how the story would end but I didn’t know how we’d get there. So I pretty much winged it, experimenting with the plot. There was no official plot outline. Just one page at a time.”

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions