BY THE END of February, Inua Ellam’s Three Sisters, based on Chekhov’s eponymous play, had run for three months at the National Theatre in London. The play chronicles the survival of three Igbo sisters through the Biafran war. It shows dreams displaced, minds metamorphosed and hopes harangued by the war.

The play starts with a rendition of folklorist chants by Oka Mbem (the chant poet) in Igbo, “No one knows how water got into the Ugbogulu fruit”, a kind of praise to God for his incomprehensible miracles. Oka Mbem reappears halfway through the play singing again in Igbo, “The story of what happened in our land is too heavy for the mouth to tell and needs answers… there is something that happened in the night, things happened in the night, things that linger till today. Our eyes have seen something”. Her powerful voice fills the hall with a sorrowful veil that enshrouds the subsequent scenes and gives the play an elegiac lift.

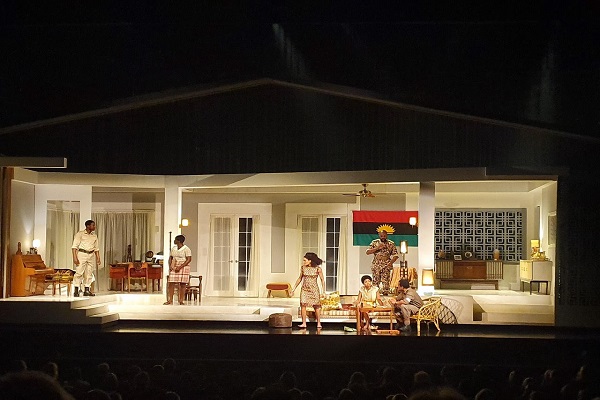

The setting in the beginning of Three Sisters is a 1950s styled porch of an English countryside house. Halfway through the play, it becomes a roomy parlour and a depleted forest filled with soot and black dust. Towards the end, most of the action takes place again in the roomy parlour and in an open field. This transition depicts the diminishing of the Igbo dream: At first, it is bright (like the siding of the house), then it becomes blighted by chaos.

Inua Ellams’ three sisters (Lolo, Nne Chukwu and Udo) like Chimamanda Adichie’s two sisters in Half Of a Yellow Sun grew up in Ikoyi, but were uprooted from there to Owerri by their idealist father 11 years before the war for cultural immersion. Yet, they fail to acknowledge it as their home even though it’s their home town—their lungs are filled still with the seaside air of Lagos and their heads (Udo’s especially) is heady with dreams of returning.

“Lagos, I want to go home,” cries Udo.

It is a cry that forces one to question where home really is in this age of globalisation. Is it the place we are born in? The place we love over the place we are born in? Is home to Anthony Joshua Watford or Ogun? Is home to Chigozie Obioma Akure or Abia? Are Igbo or Edo/Delta kids born and raised in Lagos less Lagosian than Tajudeen from Ogbomoso who migrated to Lagos at 25?

Although the play is about the titular sisters and how they survive the war and lose the house they share with their brother to his treacherous Yoruba wife, the play’s star is Peter Bankole who is amazing as Nmeri Ora. He is a pacifist and a voice of reason alongside Lolo. He wants Biafra badly like most idealists of the time; he believes it will be the first modern black nation that other black nations will imitate. He believes the new nation will be able to connect European basic science and philosophy with Igbo culture and use them as foundation for development.

He defends the common accusation that the first coup was an Igbo coup with, “They killed more Igbos in the second coup… in the second coup, they shot only us.” He’s a romantic and refuses to let his desire for Udo decay despite her unresponsiveness. He is so confident of Biafra’s victory that he bribes his way out of the army to plot a business with which he and Udo would find their purpose, even as his love is yet unrequited. He has the best lines too: “You make sadness so beautiful,” he says to her at some point when she is melancholic, as if in a trance, when confronted with the reality that she’d have to end up with what Lolo calls a “good, decent, driven man” and abandon her dreams of landing a dashing Lagos dandy who would fill her stomach with butterflies and her head with sparks.

His obsession for Udo, typified on her birthday when he ignores everyone else and stands in strategic positions to take pictures of only her, is reminiscent of Mark’s obsession for Juliet in the Richard Curtis 2003 romcom Love Actually. Sadly, towards the end of the play, he succumbs to Ikemba’s maxim that, “Happiness is an illusion. We aren’t meant to be happy; it’s the longing that motivates us,” when he gets into a needless wrestling bout with Igwe (Jonathan Ajayi) another admirer of Udo.

Perhaps the best part of Three Sisters is a scene where Lolo and Onyinyechukwu argue about the future of the Biafran curriculum. She insists that he read Kwame Nkrumah’s book on Neocolonialism. She brings up the truncation of their budding love by her England-educated but Igbo traditionalist-at-heart father who arranged for Onyinyechukwu to marry Lolo’s immediate younger sister, Nne Chukwu. The scene asserts that in life, “nothing happens as we want.”

Lolo is still hurt by Onyinyechukwu who is devoted to Nne Chukwu even as she barely tolerates him (and would rather the continuation of her affair with Ikemba (a soldier-family friend) over her marriage. Theirs is a “staid and estranging marriage” like Lucy’s in Elizabeth Strout’s 2016 novel, My name is Lucy Barton.

The success of Three Sisters is mostly dependent on the buoyancy of the actors such that little is needed in technical sciences to deliver its beauty. The actors troop in and out of the stage almost without cue and where it looks like they might have lingered, one eventually discovers it is part of the plot. The play is devoid of scenes that segue into each other without notice, and so relies on the director’s ability at cohesion to keep things from falling apart. Such that one can say its only weakness is in a few scenes where the acting is halfway between narration and dictation.

Exposing the fragility of a perennially divisive Nigeria, our adamance at accomplishing Lord Lugard’s amalgamation, and the youthful yearnings of a yeasty yesterday are subjects the play succeeds at such that at the end, even though many philosophical questions are asked during the play are unanswered, I was forced to agree with the Karl Maier title that indeed, “this house has fallen”. In addition to feeling some compassion for Udo, the crocodile that may never return to water, Lolo, who will have to propagate the British fallacy that Mungo Park discovered River Niger in her “GO-WITH-ONE-NIGERIA” school curriculum, and Nne Chukwu to whom Ikemba will become nothing but a memory.

Although I left the hall not just entertained and piqued to read more about the war, I also sensed that the play is somewhat a part of the Igbo struggle for self-determination in a way that is different from Nnamdi Kanu’s methods and Adichie’s historical novel. While IPOB’s “agitative” tactic is essential for freedom like most struggles and Adichie’s novel has kept the Biafran dream alive by resurrecting conversations about the war amongst millennials, to engage the Biafra discourse from a rich theatre perspective gives the struggle not only a more noble appeal, it is also a reminder that the negotiation of a people’s destiny is corrigible and not eternally sealed.

It will be interesting to see what resistance the play might face should the producers decide to stage it in Nigeria seeing as every pro-Biafran activism has been met with crushing opposition by the country’s democratically-elected General-President.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Osareme Edeoghon is a Nigeria-trained doctor in a lifelong affair with the arts. He writes from Somerset, England.

Osareme Edeoghon is a Nigeria-trained doctor in a lifelong affair with the arts. He writes from Somerset, England.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions