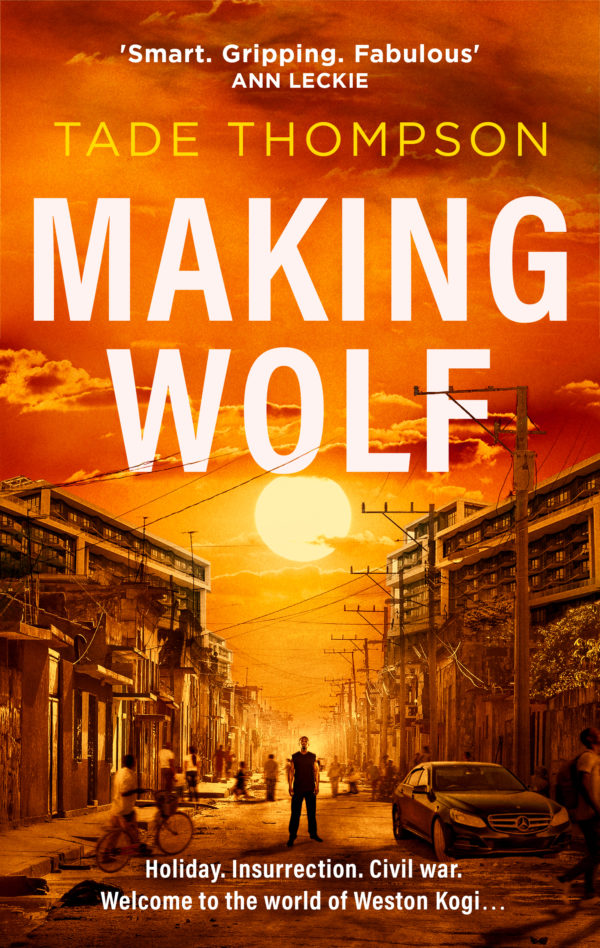

Tade Thompson is the award-winning sci-fi author who brought us the Wormwood Trilogy. On May 7th, a new edition of his 2015 novel Making Wolf was released by Little Brown and Company.

Making Wolf tells the story of Weston Kogi, hapless man who returns home, an unnamed West African country, from London only to be thrown in the middle of a murder investigation.

A classic noir fiction with all the lovable tropes and motifs, Making Wolf was optioned for film last year.

Keep reading for a little taste of Making Wolf.

BUY: Amazon UK | Waterstones

Excerpt of Making Wolf by Tade Thompson

CHAPTER 1

The lady beside me, who had spent the entire seven-hour flight reading three glossy magazines, whom I had tried to engage in conversation without success, nudged me with her elbow and thrust her jaw towards my drink.

‘If you don’t finish that, they’ll take it from you,’ she said.

She turned back to her article before I could respond. Less than a minute later, the cabin crew took my drink away.

Air travel. Never my favourite thing. Each time I had to endure descent from thirty thousand feet, I made a pact with God, and this time was no exception. Seat belt fastened, tray folded back up and locked in place, in-flight literature stowed away, back rest restored to the upright position, I gripped the armrests tightly. An announcement of some kind was not broadcast as much as beamed directly into my head. I started sweating and the landing gear struck the runway and my aunt was dead.

I held my breath until the plane was taxiing on solid ground. Dark outside, the terminal lit up like a lighthouse beacon. Other passengers undid their seat belts and started flipping on mobile phones before the plane came to a halt. I waited until the seat belt light went off and the cabin crew announced that it was all right.

Welcome to Alcacia International Airport.This is Ede.

Nobody ever welcomed you to Ede City; they just informed you that you had arrived and left you to fight or fall. Nobody wanted to be here; they only travelled to Alcacia if they had to. Like UN peacekeepers. Like UNESCO. Like me.

The passport control officer required twenty bucks American folded and tucked into the photo page. He made it disappear with consummate skill. It was both horrifying and reassuring to know that Alcacia had not changed.

Blur to the luggage carousel. This served me new anxiety, but it was unfounded. I rescued my baggage. The airport appeared cleaner than I remembered, and more people wore uniforms. I was unmolested until I reached customs, where unfit officers demanded to search my bags. They found nothing, but still stood expectant, Mona Lisa smiles breaking through their sternness. Twenty bucks American each, which was twenty more than I had budgeted for this part of the journey. I could already feel the last vestiges of my inner peace leaching away.

Arrivals seethed with people and heat and intractability. The barriers pulsed, as if they were breathing. People strained to see loved ones, and a few held placards; but most just pushed and shoved. With the exception of a few South Asians, the faces were mostly black. Nobody smiled. I dove in and fought my way to the taxi rank. I used my rusty Yoruba, but it sounded odd, even to me. I needed more practice, a few days, perhaps, but I knew I wouldn’t be here long enough to improve sufficiently. Silent, surly driver. Dark, windless night, no stars but abundant neon. Streetlights lined the first mile from the airport, but then became intermittent and stopped altogether. There was a savoury smell in the taxi, but I couldn’t place the food. The air conditioning worked, so I counted my blessings and undid the top two buttons of my shirt.

The taxi dropped me at the Ede Marriott.The women loiter- ing just outside were not guests. Only their smiles were free. I checked in and tipped the bellhop. As soon as he closed the door, I stripped off my clothes and turned on the shower. It did not work. I opened the tap, which did work, so I filled the bath and doused myself in cold water.

The last time I travelled from Alcacia International Airport was fifteen years ago. On that day, all the passengers ran with their suit- cases and backpacks across the runway to the plane. There had been an accordion connection, but an imperfect seal had led to the fall and subsequent death of three passengers, countless others injured. Their bodies lay broken, blood-wet and mangled on the tarmac when I wheeled my luggage past.

Back then, there were gunshots from beyond the terminals and the smoke trail of a rocket-propelled grenade snaked from the ground describing an arc that just missed the communications tower and ended in the ruins of a section of roof.

I remember that I lost one of my bags, dropped it while run- ning for an aircraft that looked like it was ready to start taxiing down the runway. I wouldn’t have been surprised if the pilots took off with only a third of their passengers. I kept looking back, even though I knew it was impossible for me to spot my aunt at the terminal. I was worried.The woman was fearless but didn’t know how to look out for herself. She was among hundreds of people outside the airport trying to avoid the wave of bloody revolution sweeping across Ede.

University students had been running riot for weeks. My aunt had finally saved enough money to buy me a ticket to London, England. She had packed my sister off the year before. There was widespread fear as the youths clashed with police in bloody street skirmishes that left the city fractured and charred. There were rumours of people eating fresh corpses, but it was always a friend of a friend or a distant cousin who heard it.The exodus out of the city was rapid, and people fought each other for spaces on lorries, buses and freight trains.

The students were demonstrating because the military govern- ment had promised elections and stimulated the registration of political parties, then invited the top players in all the parties to a conference, after which the conference hall just happened to blow up in a ‘gas flow malfunction’, killing all but eight. The result was an election suspended until further notice, widespread anger and the radicalisation of university students.

My aunt did not seem to be bothered. She just told me to be sure my passport was secure and that my books were packed.We set out at five a.m. I wore two layers of clothes. My aunt and I, we looked like looters.

‘When you arrive at the airport, take off the outer layer of clothes,’ she’d said. ‘Igba yen ni wa wa da bi eniyan pada.’ That is when you will look human again.

‘Yes, ma’am,’ I said.

We got into her 1980 Volkswagen Beetle and drove to the air- port on the last of her hoarded petrol. Even that early in the morning, we passed four male students beating up a policeman who lay insensate on the road.They stomped on him repeatedly and blood seeped carelessly on to the tar.

Drums beating, interrupted only by gunshots and explosions. Burning cars on every street corner. My aunt drove through all of this, and, when she came to the traffic jam on the road that led to the airport, she switched off the car and left it. We walked. We pushed through the crowds with me holding my ticket high. She bullied and bribed her way through. Without a ticket, nobody could get into the terminal so I left her pressed against the glass. My eyes misted up; apart from the crowd that crushed against her there was the danger of the violence spreading. I waved. She mouthed something that did not seem tender.

At check-in, I was searched and my rectum probed for drugs. They X-rayed me for swallowed items.There was a brief interro- gation. I had money for bribes laid out in packs of one hundred local dollars and had used them up when I got to the tunnel. When it fell apart, I shrank from the screams of the wounded and followed the rush to find alternative routes to the plane.

There were explosions and short-lived fires in the Duty Free shops as the revolutionaries reached the taxi rank, from where they could fire rockets at will and within range of the best parts of the terminal. Smoke burned my lungs as I ran and ran and ran to the plane that seemed too tiny for the number of people waving boarding passes. Knowing my countrymen, I was sure that most were forgeries.

The final scuttle up the emergency inflatable slide – yes, you can move in the reverse direction from its intended purpose.We scrambled up like contestants in a Japanese game show. I gripped plastic, slid a bit, stopped myself, continued, and gained the sum- mit in inches. After me, only two passengers made it in before the attendants said, ‘Sorry!’ and closed the doors.

As we sped away, I looked out of the window and saw people smashing up the windows of the terminal building. I hoped my aunt had got through the crowd and home safe.

The plane’s engines fired more powerfully. Gravity pressed me into my seat as the plane rose, giving me an aerial view of the city. Smoke from multiple fires. People were dying down there but I was safe. Nana was down there. My girlfriend. Her parents had fled with her to the north of Alcacia days before. I felt pangs of loneliness, but then we were in cloud and I couldn’t see Ede any more.

And now, fifteen years later, I had returned because my aunt had died. There was no smoke, no rabid university undergraduates clamouring for blood and electoral representation using surface- to-air missiles. Just me in a hotel room, standing at the window dripping wet because the only way to stay cool in the infernal heat was to shower and let the water evaporate off my skin. It was a window to nowhere. It opened to the wall of the next build- ing, and there was too much darkness to see any features.This was me in the underworld.

I sent a text message to my sister Lynn in London.

Arrived safe. You should have made the trip instead of me. I hate it here. I’ll let you know when I arrive at the ceremony. X

Her reply beeped back within thirty seconds.

You’re a Yoruba man. Alcacia is your home. You’re only renting England. Stop whining, Weston. I love you. X

I only had to survive for two days. Forty-eight hours and I would be back in London living my real life.

I couldn’t wait to leave.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions