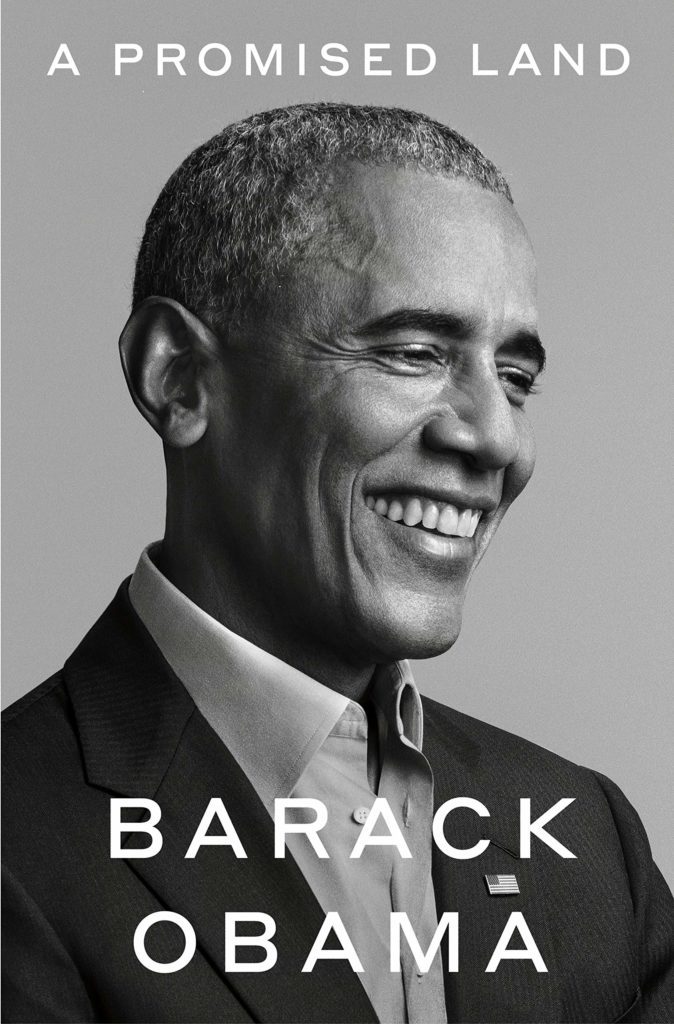

Barack Obama’s latest memoir, A Promised Land, will be published on November 17th by Crown, an imprint of Penguin Random House.

The memoir is 768 pages long and will be published in 25 languages, amounting to millions of copies worldwide in its first printing. It is so highly anticipated that the Booker Prize Foundation delayed its 2020 awards ceremony by two days so as not to clash with the release.

A Promised Land is the first of two promised volumes in which Obama looks back on the journey from his humble beginnings in politics to his second term as the president of the United States.

Obama explained in an interview with David Remnick of The New Yorker that he wrote the first draft completely “by hand, on yellow legal pads.”

***

Excerpt: The Promised Land by Barack Obama

Our first spring in the White House arrived early. As the weather warmed, the South Lawn became almost like a private park to explore. There were acres of lush grass ringed by massive, shady oaks and elms and a tiny pond tucked behind the hedges, with the handprints of Presidential children and grandchildren pressed into the paved pathway that led to it. There were nooks and crannies for games of tag and hide-and-go-seek, and there was even a bit of wildlife—not just squirrels and rabbits but a red-tailed hawk and a slender, long-legged fox that occasionally got bold enough to wander down the colonnade.

Cooped up as we’d been through the winter of 2009, we took full advantage of the new back yard. We had a swing set installed for Sasha and Malia directly in front of the Oval Office. Looking up from a late-afternoon meeting on this or that crisis, I might glimpse the girls playing outside, their faces set in bliss as they soared high on the swings.

But, of all the pleasures that first year in the White House would deliver, none quite compared to the mid-April arrival of Bo, a huggable, four-legged black bundle of fur, with a snowy-white chest and front paws. Malia and Sasha, who’d been lobbying for a puppy since before the campaign, squealed with delight upon seeing him for the first time, letting him lick their ears and faces as the three of them rolled around on the floor.

A note from our editor about this excerpt, drawn from President Obama’s forthcoming memoir.

With Bo, I got what someone once described as the only reliable friend a politician can have in Washington. He also gave me an added excuse to put off my evening paperwork and join my family on meandering after-dinner walks around the South Lawn. It was during those moments—with the light fading into streaks of purple and gold, Michelle smiling and squeezing my hand as Bo bounded in and out of the bushes with the girls giving chase—that I felt normal and whole and as lucky as any man has a right to expect.

Bo had come to us as a gift from Ted Kennedy and his wife, Vicki, part of a litter that was related to Teddy’s own beloved pair of Portuguese water dogs. It was a truly thoughtful gesture—not only because the breed was hypoallergenic (a necessity, owing to Malia’s allergies) but also because the Kennedys had made sure that Bo was housebroken before he came to us. When I called to thank them, though, it was only Vicki I could speak with. It had been almost a year since Teddy was diagnosed with a malignant brain tumor, and although he was still receiving treatment in Boston, it was clear to everyone—Teddy included—that the prognosis was not good.

I’d seen him in March, when he’d made a surprise appearance at a White House conference we held to get the ball rolling on universal-health-care legislation. Teddy’s walk was unsteady that day; his suit draped loosely on him after all the weight he’d lost, and despite his cheerful demeanor his pinched, cloudy eyes showed the strain it took just to hold himself upright. And yet he’d insisted on coming anyway, because thirty-five years earlier the cause of getting everyone decent, affordable health care had become personal for him. His son Teddy, Jr., had been diagnosed with a bone cancer that led to a leg amputation at the age of twelve. While at the hospital, Teddy had come to know other parents whose children were just as ill but who had no idea how they’d pay the mounting medical bills. Then and there, he had vowed to do something to change that.

Through seven Presidents, Teddy had fought the good fight. During the Clinton Administration, he helped secure passage of the Children’s Health Insurance Program. Over the objections of some in his own party, he worked with President George W. Bush to get drug coverage for seniors. But, for all his power and legislative skill, the dream of establishing universal health care—a system that delivered good-quality medical care to all people, regardless of their ability to pay—continued to elude him.

Which is why he had forced himself out of bed to come to our conference, knowing his brief but symbolic presence might have an effect. Sure enough, when he walked into the East Room, the hundred and fifty people who were present erupted into lengthy applause. His remarks were short; his baritone didn’t boom quite as loudly as it used to when he’d roared on the Senate floor. By the time we’d moved on to the third or fourth speaker, Vicki had quietly escorted him out the door.

I saw him only once more in person, six weeks later, at a signing ceremony for a bill expanding national-service programs, which Republicans and Democrats alike had named in his honor. But I would think of Teddy sometimes when Bo wandered into the Treaty Room and curled up at my feet. And I’d recall what Teddy had told me that day, just before we walked into the East Room together. “This is the time, Mr. President,” he had said. “Don’t let it slip away.”

The quest for some form of universal health care in the United States dates back to 1912, when Theodore Roosevelt, who had previously served nearly eight years as a Republican President, decided to run again—this time on a progressive ticket and with a platform that called for the establishment of a centralized national health service. At the time, few people had or felt the need for private health insurance. Most Americans paid their doctors visit by visit, but the field of medicine was quickly growing more sophisticated, and as more diagnostic tests and surgeries became available the attendant costs began to rise, tying health more obviously to wealth. Both the United Kingdom and Germany had addressed similar issues by instituting national health-insurance systems, and other European nations would eventually follow suit. Although Roosevelt ultimately lost the 1912 election, his party’s progressive ideals planted a seed: accessible and affordable medical care might one day be viewed as a right more than a privilege. It wasn’t long, however, before doctors and Southern politicians vocally opposed any type of government involvement in health care, branding it as a form of Bolshevism.

After Franklin Delano Roosevelt imposed a nationwide wage freeze, during the Second World War, meant to stem inflation, many companies began offering private health insurance and pension benefits as a way to compete for the limited number of workers not deployed overseas. Once the war ended, this employer-based system continued, in no small part because labor unions used the more generous benefit packages negotiated under collective-bargaining agreements as a selling point to recruit new members. The downside was that those unions then had little motivation to push for government-sponsored health programs that might help everybody else. Harry Truman proposed a national health-care system twice, once in 1945 and again as part of his Fair Deal package, in 1949, but his appeal for public support was no match for the well-financed P.R. efforts of the American Medical Association and other industry lobbyists. Opponents didn’t just kill Truman’s effort. They convinced a large swath of the public that “socialized medicine” would lead to rationing, to the loss of the family doctor and of the freedoms Americans hold so dear.

Rather than challenging private insurance head on, progressives shifted their energy to helping those populations the marketplace had left behind. These efforts bore fruit during Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society campaign, when a universal single-payer program partially funded by payroll-tax revenue was introduced for seniors (Medicare) and a not so comprehensive program based on a combination of federal and state funding was set up for the poor (Medicaid). During the nineteen-seventies and early eighties, this patchwork system functioned well enough, with roughly eighty per cent of Americans covered through either their jobs or one of these two programs. Meanwhile, defenders of the status quo could point to the many innovations brought to market by the for-profit medical industry, from MRIs to lifesaving drugs.

Useful as these innovations were, though, they also drove up health-care costs. And, with insurers footing the nation’s medical bills, patients had little incentive to question whether drug companies were overcharging or whether doctors and hospitals were ordering redundant tests and unnecessary treatments in order to pad their bottom lines. At the same time, nearly a fifth of the country lived just an illness or an accident away from potential financial ruin. Unable to afford regular checkups and preventive care, the uninsured often waited until they were very sick before seeking attention at hospital emergency rooms, where more advanced illnesses meant more expensive treatment. Hospitals made up for this uncompensated care by increasing prices for insured customers, which further jacked up premiums.

All this explained why the United States spent a lot more money per person on health care than any other advanced economy (eighty-seven per cent more than Canada, a hundred and two per cent more than France, a hundred and eighty-two per cent more than Japan), and for similar or worse results. The difference amounted to hundreds of billions of dollars a year—money that could have been used instead to provide child care for American families, or to reduce college tuition, or to eliminate a good chunk of the federal deficit. Spiralling health-care costs also burdened American businesses: Japanese and German automakers didn’t have to worry about the extra fifteen hundred dollars in worker and retiree health-care costs that Detroit had to build into the price of every car rolling off the assembly line.

In fact, it was in response to foreign competition that U.S. companies began off-loading rising insurance costs onto their employees in the late nineteen-eighties and nineties, replacing traditional plans that had few, if any, out-of-pocket costs with cheaper versions that included co-pays, lifetime limits, higher deductibles, and other unpleasant surprises hidden in the fine print. Unions often found themselves able to preserve their traditional benefit plans only by agreeing to forgo increases in wages. Small businesses found it tough to provide their workers with health benefits at all. Meanwhile, insurance companies that operated in the individual market perfected the art of rejecting customers who, according to their actuarial data, were most likely to make use of the health-care system, especially anyone with a “preexisting condition”—which they often defined as anything from a previous bout of cancer to asthma and chronic allergies.

It’s no wonder, then, that by the time I took office there were very few people ready to defend the existing system. More than forty-three million Americans were now uninsured, premiums for family coverage had risen ninety-seven per cent since 2000, and costs were only continuing to climb. And yet the prospect of trying to get a big health-care-reform bill through Congress at the height of a historic recession made my team nervous. Even my adviser David Axelrod—who had experienced the challenges of getting specialized care for a daughter with severe epilepsy and had left journalism to become a political consultant in part to pay for her treatment—had his doubts.

“The data’s pretty clear,” he said when we discussed the topic with Rahm Emanuel, my chief of staff. “People may hate the way things work in general, but most of them have insurance. They don’t really think about the flaws in the system until somebody in their own family gets sick. They like their doctor. They don’t trust Washington to fix anything. And, even if they think you’re sincere, they worry that any changes you make will cost them money and help somebody else.”

“What Axe is trying to say, Mr. President,” Rahm interrupted, his face screwed up in a frown, “is that this can blow up in our faces.”

We were already using up precious political capital, Rahm said, in order to fast-track the passage of the Recovery Act, a major economic-stimulus package. As an adviser in the Clinton White House, he’d had a front-row seat at the last push for universal health care, when Hillary Clinton’s legislative proposal crashed and burned, and he was quick to remind us that the backlash had contributed to Democrats’ losing control of the House in the 1994 midterms. “Republicans will say health care is a big new liberal spending binge, and that it’s a distraction from solving the economic crisis,” Rahm said.

“Unless I’m missing something,” I said, “we’re doing everything we can do on the economy.”

“I know that, Mr. President. But the American people don’t know that.”

“So what are we saying here?” I asked. “That despite having the biggest Democratic majorities in decades, despite the promises we made during the campaign, we shouldn’t try to get health care done?”

Rahm looked to Axe for help.

“We all think we should try,” Axe said. “You just need to know that, if we lose, your Presidency will be badly weakened. And nobody understands that better than McConnell and Boehner.”

I stood up, signalling that the meeting was over. “We better not lose, then,” I said.

When I think back to those early conversations, it’s hard to deny my overconfidence. I was convinced that the logic of health-care reform was so obvious that even in the face of well-organized opposition I could rally the American people’s support. Other big initiatives—like immigration reform and climate-change legislation—would probably be even harder to get through Congress; I figured that scoring a victory on the item that most affected people’s day-to-day lives was our best shot at building momentum for the rest of my legislative agenda. As for the political hazards that Axe and Rahm worried about, the recession virtually guaranteed that my poll numbers were going to take a hit anyway. Being timid wouldn’t change that reality. Even if it did, passing up a chance to help millions of people just because it might hurt my reëlection prospects—well, that was exactly the kind of myopic, self-preserving behavior I’d vowed to reject.

My interest in health care went beyond policy or politics; it was personal, just as it was for Teddy. Each time I met a parent struggling to come up with the money to get treatment for a sick child, I thought back to the night Michelle and I had to take three-month-old Sasha to the emergency room for what turned out to be viral meningitis. I remembered the terror and the helplessness we felt as the nurses whisked her away for a spinal tap, and the realization that we might never have caught the infection in time had the girls not had a regular pediatrician we felt comfortable calling in the middle of the night. Most of all, I thought about my mom, who had died in 1995, of uterine cancer.

In mid-June, I headed to Green Bay, Wisconsin, for the first in a series of health-care town-hall meetings we would hold around the country, hoping to solicit citizen input and educate people on the possibilities for reform. Introducing me that day was a local resident named Laura Klitzka, who was thirty-five years old and had been diagnosed with aggressive breast cancer that had spread to her bones. Even though she was on her husband’s insurance plan, repeated rounds of surgery, radiation, and chemo had bumped her up against the policy’s lifetime limits, leaving the couple with twelve thousand dollars in unpaid medical bills. Over the objections of her husband, Peter, she was now pondering whether more treatment was worth it. Sitting in their living room before we headed for the event, she smiled wanly as we watched Peter doing his best to keep track of their two young kids playing on the floor.

“I want as much time with them as I can get, but I don’t want to leave them with a mountain of debt,” she said to me. “It feels selfish.” Her eyes started misting, and I held her hand, remembering my mom wasting away in those final months: the times she’d put off checkups that might have caught her disease because she was in between consulting contracts and didn’t have coverage; the stress she carried to her hospital bed when her insurer refused to pay her disability claim, arguing that she had failed to disclose a preëxisting condition, despite the fact that she hadn’t even been diagnosed when her policy started. The unspoken regrets.

Passing a health-care bill wouldn’t bring my mom back. It wouldn’t douse the guilt I still felt for not having been at her side when she took her last breath. It would probably come too late to help Laura Klitzka and her family. But it would save somebody’s mom, somewhere down the line. And that was worth fighting for.

The question was whether we could get it done. Any major health-care bill meant rejiggering a sixth of the American economy. Legislation of this scope was guaranteed to involve hundreds of pages of endlessly fussed-over amendments and regulations. A single provision tucked inside the bill could translate to billions of dollars in gains or losses for some sector of the health-care industry. A shift in one number, a zero here or a decimal point there, could mean a million more families getting coverage—or not. Across the country, insurance companies were major employers, and local hospitals served as the economic anchor for many small towns and counties. People had good reasons—life-and-death reasons—to worry about how any change would affect them.

There was also the question of how to pay for the changes. To cover more people, I argued, America didn’t need to spend more money on health care; we just needed to use that money more wisely. In theory, that was true. But one person’s waste and inefficiency was another person’s profit or convenience; spending on coverage would show up on the federal books much sooner than the savings from reform; and, unlike the insurance companies or Big Pharma, whose shareholders expected them to be on guard against any change that might cost them a dime, most of the potential beneficiaries of reform—the waitress, the family farmer, the independent contractor, the cancer survivor—didn’t have gaggles of well-paid and experienced lobbyists roaming the halls of Congress.

In other words, both the politics and the substance of health care were mind-numbingly complicated. I was going to have to explain to the American people, including those with high-quality health insurance, why and how reform could work. For this reason, I thought we’d use as open and transparent a process as possible. “Everyone will have a seat at the table,” I’d told voters during the campaign. “Not negotiating behind closed doors, but bringing all parties together, and broadcasting those negotiations on C-span, so that the American people can see what the choices are.” When I later brought this idea up with Rahm, he looked like he wished I weren’t the President, just so he could more vividly explain the stupidity of my plan. If we were going to get a bill passed, he told me, the process would involve dozens of deals and compromises along the way—and it wasn’t going to be conducted like a civics seminar.

“Making sausage isn’t pretty, Mr. President,” he said. “And you’re asking for a really big piece of sausage.”

One thing Rahm and I did agree on was that we had months of work ahead of us, and we needed a topnotch health-care team to keep us on track. Luckily, we were able to recruit a remarkable trio of women to help run the show. Kathleen Sebelius, the two-term Democratic governor of Republican-leaning Kansas, came on as Secretary of Health and Human Services. Jeanne Lambrew, a professor at the University of Texas and an expert on Medicare and Medicaid, became the director of the H.H.S. Office of Health Reform, basically our chief policy adviser.

It was Nancy-Ann DeParle whom I would come to rely on most as our campaign took shape. A Tennessee lawyer who had run that state’s health programs before serving as the Medicare administrator in the Clinton Administration, Nancy-Ann carried herself with the crisp professionalism of someone accustomed to seeing hard work translate into success. How much of that drive could be traced to her experiences growing up Chinese-American in a tiny Tennessee town, I couldn’t say. I did know that when she was seventeen her mom died of lung cancer. It seems I wasn’t the only one for whom getting health care passed was personal.

Our team began to map out a legislative strategy. Based on our experiences with the Recovery Act, we had no doubt that Mitch McConnell would do everything he could to torpedo our efforts, and that the chances of getting Republican votes in the Senate were slim. We could take heart from the fact that, instead of the fifty-eight senators who were caucusing with the Democrats when we passed the stimulus bill, we were likely to have sixty by the time any health-care bill actually came to a vote. Al Franken had finally taken his seat after a contentious election recount in Minnesota, and Arlen Specter had decided to switch parties after being effectively driven out of the G.O.P. for supporting the Recovery Act.

This would give us a filibuster-proof majority, but our head count was tenuous: it included the terminally ill Ted Kennedy and the frail and ailing Robert Byrd, of West Virginia, not to mention conservative Democrats like Nebraska’s Ben Nelson (a former insurance-company executive), who could go sideways on us at any minute. Beyond wanting some margin for error, I also knew that passing something as monumental as health-care reform on a purely party-line vote would make the law politically more vulnerable down the road. So we thought it made sense to shape our legislative proposal in such a way that it at least had a chance of winning over a handful of Republicans.

Fortunately, we had a model to work with—one that, ironically, had grown out of a partnership between Ted Kennedy and the former Massachusetts governor Mitt Romney. A few years earlier, confronting budget shortfalls and the prospect of losing Medicaid funding, Romney had become fixated on finding a way to get more Massachusetts residents properly insured, which would then reduce state spending on emergency care for the uninsured and, ideally, lead to a healthier population in general.

He and his staff came up with a multipronged approach in which every person would be required to purchase health insurance (an “individual mandate”), the same way every car owner was required to carry auto insurance. Middle-income people who couldn’t get insurance through their job, didn’t qualify for Medicare or Medicaid, and were unable to afford insurance on their own would get a government subsidy to buy coverage. Subsidies would be determined on a sliding scale according to each person’s income, and a central online marketplace—an “exchange”—would be set up so that consumers could shop for the best insurance deal. Insurers, meanwhile, would no longer be allowed to deny coverage based on preëxisting conditions.

These two ideas—the individual mandate and protecting people with preëxisting conditions—went hand in hand. With a huge new pool of government-subsidized customers, insurers no longer had a financial incentive for trying to cherry-pick only the young and the healthy for coverage. And the mandate would prevent people from gaming the system by waiting until they got sick to purchase insurance. Touting the plan to reporters, Romney called the individual mandate “the ultimate conservative idea,” because it promoted personal responsibility.

Not surprisingly, Massachusetts’s Democratic-controlled state legislature had initially been suspicious of the Romney plan, and not just because a Republican had proposed it; among many progressives, the need to replace private insurance and for-profit health care with a single-payer system like Canada’s was an article of faith. Had we been starting from scratch, I would have agreed with them; the evidence from other countries showed that a single, national system—basically, Medicare for All—was a cost-effective way to deliver health care. But neither Massachusetts nor the United States was starting from scratch. Teddy, who despite his reputation as a wide-eyed liberal was ever practical, understood that trying to dismantle the existing system and replace it with an entirely new one would be both a nonstarter politically and hugely disruptive to the economy. Instead, he’d embraced the Romney proposal and helped the Governor line up the Democratic votes in the state legislature required to get it passed into law.

“Romneycare,” as it eventually became known, was now two years old and had been a clear success, driving the uninsured rate in Massachusetts down to just under four per cent, the lowest in the country. Teddy had used it as the basis for draft legislation he had started preparing many months ahead of the election, in his role as the chair of the Senate Health and Education Committee. And, though Axe and my campaign manager, David Plouffe, had persuaded me to hold off on endorsing the Massachusetts approach during my run for President—the idea of requiring people to buy insurance was extremely unpopular with voters, and I’d instead focussed my plan on lowering costs—I was now convinced, as were most health-care advocates, that Romney’s model offered us the best chance of achieving universal coverage.

People still differed on the details of what a national version of the Massachusetts plan might look like, and a number of advocates urged us to settle these issues early by putting out a specific White House proposal for Congress to follow. We decided against that. One of the lessons from the Clintons’ failed effort was the need to involve key Democrats in the process, so that they would feel a sense of ownership of the bill. Insufficient coördination, we knew, could result in legislative death by a thousand cuts.

On the House side, this meant working with old-school liberals like Henry Waxman, the wily, pugnacious congressman from California and the head of the Energy and Commerce Committee, which had jurisdiction over health care. In the Senate, the landscape was different: with Teddy convalescing, the main player was Max Baucus, a conservative Democrat from Montana, who chaired the powerful Finance Committee, and had a close friendship with the Iowa senator Chuck Grassley, the Finance Committee’s ranking Republican. Baucus was optimistic that he could win Grassley’s support for a bill.

“Trust me, Mr. President,” Baucus said. “Chuck and I have already discussed it. We’re going to have this thing done by July.”

Every job has its share of surprises. A key piece of equipment breaks down. A traffic accident forces a change in delivery routes. A client calls to say you’ve won the contract—but they need the order filled three months earlier than planned. No matter where you work, you need to be able to improvise to meet your objectives, or at least to cut your losses.

The Presidency was no different. In the course of the spring and summer of that first year, as we wrestled with the financial crisis, two wars, and the push for health-care reform, another unexpected item got added to an already overloaded agenda. In April, reports surfaced of a worrying flu outbreak in Mexico. The flu virus usually hits vulnerable populations like the elderly, infants, and asthma sufferers hardest, but this strain appeared to strike young, healthy people—and was killing them at a higher than usual rate. Within weeks, people in the United States were falling ill with the virus: one in Ohio, two in Kansas, eight in a single high school in New York City. By the end of the month, both our own Centers for Disease Control and the World Health Organization had confirmed that we were dealing with a variation of the H1N1 virus. In June, the W.H.O. officially declared the first global pandemic in forty years.

I had more than a passing knowledge of H1N1 after working on U.S. pandemic preparedness when I was in the Senate. What I knew scared the hell out of me. Starting in 1918, a strain of H1N1 that came to be known as the “Spanish flu” had infected an estimated half a billion people and killed as many as a hundred million—around five per cent of the world’s population. In Philadelphia alone, more than twelve thousand died in the span of a few weeks. The effects of the pandemic went beyond the stunning death tolls and the shutdown of economic activity; later research revealed that those who were in utero during the pandemic grew up to have lower incomes, poorer educational outcomes, and higher rates of physical disability.

It was too early to tell how deadly this new virus would be. But I wasn’t interested in taking any chances. On the same day that Kathleen Sebelius was confirmed as H.H.S. Secretary, we sent a plane to pick her up from Kansas, flew her to Washington to be sworn in at a makeshift ceremony in the Oval Office, and immediately asked her to lead a two-hour conference call with W.H.O. officials and health ministers from Mexico and Canada. A few days later, we pulled together an interagency team to evaluate how ready the United States was for a worst-case scenario.

The answer was that we weren’t at all ready. Annual flu shots didn’t provide much protection against H1N1, it turned out, and, because vaccines generally weren’t a moneymaker for drug companies, the few U.S. vaccine-makers that existed had a limited capacity to ramp up production of a new one. Then, we faced questions of how to distribute antiviral medicines, what guidelines hospitals used in treating cases of the flu, and even how we’d handle the possibility of closing schools and imposing quarantines if things got significantly worse. Several veterans of the Ford Administration’s 1976 swine-flu response team warned us of the difficulties involved in getting out in front of an outbreak without overreacting or triggering a panic. Apparently, President Ford, wanting to act decisively in the middle of a reëlection campaign, had fast-tracked vaccinations before the severity of the pandemic had been determined, with the result that more Americans developed a neurological disorder connected to the vaccine than died from the flu.

“You need to be involved, Mr. President,” one of Ford’s staffers advised, “but you need to let the experts run the process.”

My instructions to the public-health team were simple: decisions would be made based on the best available science, and we were going to explain to the public each step of our response—including detailing what we did and didn’t know. Over the course of the next six months, we did exactly that. A summertime dip in H1N1 cases gave the team time to work with drugmakers and incentivize new processes for quicker vaccine production. They pre-positioned medical supplies across regions and gave hospitals increased flexibility to manage a surge in flu cases. They evaluated—and ultimately rejected—the idea of closing schools for the rest of the year, but worked with school districts, businesses, and state and local officials to make sure that everyone had the resources they needed to respond in the event of an outbreak.

Although the United States did not escape unscathed—more than twelve thousand Americans lost their lives—we were fortunate that this particular strain of H1N1 turned out to be less deadly than the experts had feared. News that the pandemic had abated by mid-2010 didn’t generate headlines. Still, I took great pride in how well our team had performed. Without fanfare or fuss, they not only helped keep the virus contained but strengthened our readiness for any future public-health emergency—which would make all the difference several years later, when the Ebola outbreak in West Africa triggered a full-blown panic.

This, I was coming to realize, was the nature of the Presidency: sometimes your most important work involved the stuff nobody noticed.

The slow march toward health-care reform consumed much of the summer. As the legislation lumbered through Congress, we looked for any opportunity to help keep the process on track. The good news was that the key Democratic chairs—especially Baucus and Waxman—were working hard to craft bills that they could pass out of their respective committees before the traditional August recess. The bad news was that the more everyone dug into the details of reform, the more differences in substance and strategy emerged—not just between Democrats and Republicans but between House and Senate Democrats, between the White House and congressional Democrats, and even between members of my own team.

Most of the arguments revolved around the issue of how to generate a mixture of savings and new revenue to pay for expanding coverage to millions of uninsured Americans. Baucus, given his interest in producing a bipartisan bill, hoped to avoid anything that could be characterized as a tax increase. Instead, he and his staff had calculated the windfall profits that a new flood of insured customers would bring to hospitals, drug companies, and insurers, and had used those figures as a basis for negotiating billions of dollars in up-front contributions—through fees or Medicare-billing reductions—from each industry. To sweeten the deal, Baucus was also prepared to make certain policy concessions. For example, he promised the pharmaceutical lobbyists that his bill wouldn’t include provisions allowing the reimportation of drugs from Canada—a popular Democratic proposal that highlighted the way Canadian and European government-run health-care systems used their immense bargaining power to negotiate much lower prices than Big Pharma charged in the United States.

Politically and emotionally, I would have found it a lot more satisfying to just go after the drug and insurance companies and see if we could beat them into submission. They were wildly unpopular with voters, and for good reason. But, as a practical matter, it was hard to argue with Baucus’s more conciliatory approach. We had no way to get to sixty votes in the Senate for a major health-care bill without at least the tacit agreement of the big industry players. Drug reimportation was a great political issue, but, at the end of the day, we didn’t have the votes for it, partly because plenty of Democrats had major pharmaceutical companies headquartered or operating in their states.

With these realities in mind, I signed off on having Rahm, Nancy-Ann, and my deputy chief of staff, Jim Messina, sit in on Baucus’s negotiations with health-care-industry representatives. By the end of June, they’d hashed out a deal, securing hundreds of billions of dollars in givebacks and broader drug discounts for seniors using Medicare. Just as important, they’d gotten a commitment from the hospitals, insurers, and drug companies to support—or at least not oppose—the emerging bill.

It was a big hurdle to clear, a case of politics as the art of the possible. But for some of the more liberal Democrats in the House, where no one had to worry about a filibuster, and among progressive advocacy groups that were still hoping to lay the groundwork for a single-payer health-care system, our compromises smacked of capitulation, a deal with the devil. It didn’t help that, as Rahm had predicted, none of the negotiations with the industry had been broadcast on C-span. The press started reporting on details of what they called “backroom deals.” More than a few constituents wrote in to ask whether I’d gone over to the dark side. And Waxman made a point of saying he didn’t consider his work bound by whatever concessions Baucus or the White House had made to industry lobbyists.

Quick as the House Democrats were to mount their high horse, they were also more than willing to protect the status quo when it secured their prerogatives or benefitted politically influential constituencies. For example, more or less every health-care economist agreed that it wasn’t enough just to pry money out of insurance- and drug-company profits and use it to cover more people; in order for reform to work, we also had to do something about the skyrocketing costs charged by doctors and hospitals. Otherwise, any new money put into the system would yield less and less care for fewer and fewer people over time. One of the best ways to “bend the cost curve” was to establish an independent board, shielded from politics and special-interest lobbying, that would set reimbursement rates for Medicare based on the comparative effectiveness of particular treatments.

House Democrats hated the idea. It would mean giving away their power to determine what Medicare did and didn’t cover (along with the potential campaign fund-raising opportunities that came with that power). They also worried that they’d get blamed by cranky seniors who found themselves unable to get the latest drug or diagnostic test advertised on TV, even if an expert could prove that it was actually a waste of money.

They were similarly skeptical of the other big proposal to control costs: a cap on the tax deductibility of so-called Cadillac insurance plans—high-cost, employer-provided policies that paid for all sorts of premium services but didn’t improve health outcomes. Other than corporate managers and well-paid professionals, union members made up the main group covered by such plans, and the unions were adamantly opposed to what would come to be known as “the Cadillac tax.” It didn’t matter to labor leaders that their members might be willing to trade a deluxe hospital suite or a second, unnecessary MRI for a chance at higher take-home pay. And so long as the unions were opposed to the Cadillac tax, most House Democrats were going to be, too.

The squabbles quickly found their way into the press, making the whole process appear messy and convoluted. By late July, polls showed that more Americans disapproved than approved of the way I was handling health-care reform, prompting me to complain to Axe about our communications strategy. “We’re on the right side of this stuff,” I insisted. “We just have to explain it better to voters.”

Axe was irritated that his shop was seemingly getting blamed for the very problem he’d warned me about from the start. “You can explain it till you’re blue in the face,” he told me. “But people who already have health care are skeptical that reform will benefit them, and a whole bunch of facts and figures won’t change that.”

Toward the end of the month, versions of the health-care bill had passed out of all the relevant House committees. The Senate Health and Education Committee had completed its work as well. All that remained was getting a bill through Max Baucus’s Senate Finance Committee. Once that was done, we could consolidate the different versions into one House and one Senate bill, ideally passing each before the August recess, with the goal of having a final version of the legislation on my desk for signing before the end of the year.

No matter how hard we pressed, though, we couldn’t get Baucus to complete his work. As the summer wore on, his optimism that he could produce a bipartisan bill began to look delusional. The Republican Minority Leaders, McConnell and John Boehner, had already announced their vigorous opposition to our legislative efforts, arguing that they represented an attempted “government takeover” of the health-care system. Frank Luntz, a well-known Republican strategist, had circulated a memo stating that, after market-testing some thirty anti-reform messages, he’d concluded that invoking a government takeover was the best way to discredit the health-care legislation. From that point on, conservatives followed the script, repeating the phrase like an incantation.

Senator Jim DeMint, the conservative firebrand from South Carolina, was more transparent about his party’s intentions. “If we’re able to stop Obama on this, it will be his Waterloo,” he announced on a nationwide conference call with conservative activists. “It will break him.”

Unsurprisingly, given the atmosphere, the group of three G.O.P. senators who had been invited to participate in bipartisan talks with Baucus was now down to two: Chuck Grassley and Olympia Snowe, the moderate from Maine. My team and I did everything we could to help Baucus win their support. I had Grassley and Snowe over to the White House repeatedly and called them every few weeks to take their temperature. We signed off on scores of changes they wanted made to Baucus’s draft bill. Nancy-Ann became a permanent fixture in their Senate offices and took Snowe out to dinner so often that we joked that her husband was getting jealous.

“Tell Olympia she can write the whole damn bill!” I said to Nancy-Ann as she was leaving for one such meeting. “We’ll call it the Snowe plan. Tell her if she votes for the bill she can have the White House—Michelle and I will move to an apartment!”

And still we were getting nowhere. Snowe took pride in her centrist reputation, but the Republican Party’s sharp rightward tilt had left her increasingly isolated within her own caucus.

Grassley was a different story. He talked a good game about wanting to help the family farmers back in Iowa who had trouble getting insurance they could count on, and when Hillary Clinton had pushed health-care reform, in the nineties, Grassley had actually co-sponsored an alternative that in many ways resembled the Massachusetts-style plan we were proposing, complete with an individual mandate. But, unlike Snowe, Grassley rarely bucked his party’s leadership on tough issues. With his long, hangdog face and throaty Midwestern drawl, he would hem and haw about this or that problem he had with the bill without ever telling us what exactly it would take to get him to yes. Phil Schiliro, who ran the White House’s legislative-affairs department, thought that Grassley was just stringing Baucus along at McConnell’s behest, trying to stall the process and prevent us from moving on to the rest of our agenda. Even I, the resident White House optimist, finally got fed up and asked Baucus to come by for a visit.

“Time’s up, Max,” I told him in the Oval during a meeting in late July. “You’ve given it your best shot. Grassley’s gone. He just hasn’t broken the news to you yet.”

Baucus shook his head. “I respectfully disagree, Mr. President,” he said. “I know Chuck. I think we’re this close to getting him.” He held his thumb and index finger an inch apart, smiling at me like someone who’s discovered a cure for cancer and is forced to deal with foolish skeptics. “Let’s just give Chuck a little more time and have the vote when we get back from recess.”

A part of me wanted to get up, grab Baucus by the shoulders, and shake him till he came to his senses. I decided that this wouldn’t work. Another part of me considered threatening to withhold my political support the next time he ran for reëlection, but since he polled higher than I did in his home state of Montana, I figured that wouldn’t work, either. Instead, I argued and cajoled for another half hour, finally agreeing to his plan to delay an immediate party-line vote and instead call the bill to a vote within the first two weeks of Congress’s reconvening in September.

With the House and the Senate adjourned and both votes still looming, we decided I’d spend the first two weeks of August on the road, holding health-care town halls in places like Montana and Colorado, where public support for reform was shakiest. As a sweetener, my team suggested that Michelle and the girls join me, and that we visit some national parks along the way.

I was thrilled by the suggestion. It’s not as if Malia and Sasha were deprived of fatherly attention or in need of extra summer fun—they’d had plenty of both, with playdates and movies and a whole lot of loafing. Often, I’d come home in the evening and go up to the third floor to find the solarium overtaken by pajama-clad eight- or eleven-year-old girls settling in for a sleepover, bouncing on inflatable mattresses, scattering popcorn and toys everywhere, giggling non-stop at whatever was on Nickelodeon.

But, as much as Michelle and I (with the help of infinitely patient Secret Service agents) tried to approximate a normal childhood for our daughters, it was hard, if not impossible, for me to take them places like an ordinary dad would. We couldn’t go to an amusement park together, making an impromptu stop for burgers along the way. I couldn’t take them, as I once had, on lazy Sunday-afternoon bike rides. A trip to get ice cream or a visit to a bookstore was now a major production, involving road closures, tactical teams, and the omnipresent press pool.

If the girls felt a sense of loss over this, they didn’t show it. But I felt it acutely. I especially mourned the fact that I’d probably never get a chance to take Malia and Sasha on the sort of long summer road trip I’d made when I was eleven, after my mother and my grandmother, Toot, decided it was time for Maya and me to see the mainland of the United States. It had lasted a month and burned a lasting impression into my mind—and not just because we went to Disneyland (although that was obviously outstanding). We had dug for clams during low tide in Puget Sound, ridden horses through a creek at the base of Canyon de Chelly, in Arizona, watched the endless Kansas prairie unfold from a train window, spotted a herd of bison on a dusky plain in Yellowstone, and ended each day with the simple pleasures of a motel ice machine, the occasional swimming pool, or just air-conditioning and clean sheets. That one trip gave me a glimpse of the dizzying freedom of the open road, how vast America was, and how full of wonder.

I couldn’t duplicate that experience for my daughters—not when we flew on Air Force One, rode in motorcades, and never bunked down in a place like Howard Johnson’s. Getting from point A to point B happened too fast and too comfortably, and the days were too stuffed with prescheduled, staff-monitored activity—absent that familiar mixture of surprises, misadventures, and boredom—to fully qualify as a road trip. But in the course of an August week we watched Old Faithful blow, and looked out over the ochre expanse of the Grand Canyon. The girls went inner-tubing. At night, we played board games and tried to name the constellations. Tucking my daughters into bed, I hoped that, despite all the fuss that surrounded us, their minds were storing away a vision of life’s possibilities and the beauty of the American landscape, just as mine once had; and that they might someday think back on our trips together and be reminded that they were so worthy of love, so fascinating and electric with life, that there was nothing their parents would rather do than share those vistas with them.

Of course, one of the things Malia and Sasha had to put up with on the trip out West was their dad peeling off every other day to talk about health care. The town halls themselves weren’t very different from the ones I’d held in the spring. People shared stories about how the existing health-care system had failed their families, and asked questions about how the emerging bill might affect their own insurance. Even those who opposed our effort listened attentively to what I had to say.

Outside, though, the atmosphere was very different. We were in the middle of what came to be known as the “Tea Party summer,” an organized effort to marry people’s honest fears about a changing America with a right-wing political agenda. Heading to and from every venue, we were greeted by dozens of angry protesters. Some shouted through bullhorns. Others flashed a single-fingered salute. Many held up signs with messages like “obamacare sucks” or the unintentionally ironic “keep government out of my medicare.” Some waved doctored pictures of me looking like Heath Ledger’s Joker, in “The Dark Knight,” with blackened eyes and thickly caked makeup, appearing almost demonic. Still others wore Colonial-era patriot costumes and hoisted the “don’t tread on me” flag. All of them seemed most interested in expressing their general contempt for me, a sentiment best summed up by a refashioning of the famous Shepard Fairey poster from our campaign: the same red-white-and-blue rendering of my face, but with the word “hope” replaced by “nope.”

This new and suddenly potent force in American politics had started months earlier, as a handful of ragtag, small-scale protests against bank bailouts and the Recovery Act. A number of the early participants had apparently migrated from the quixotic, libertarian Presidential campaign of the Republican congressman Ron Paul, who called for the elimination of the federal income tax and the Federal Reserve, a return to the gold standard, and withdrawal from the U.N. and nato. The group was now focussed on stopping the abomination they called “Obamacare,” which they insisted would introduce a socialistic, oppressive new order to America. As I was conducting my relatively sedate health-care town halls out West, newscasts started broadcasting scenes from parallel congressional events around the country, with House and Senate members suddenly confronted by angry, heckling crowds in their home districts, and Tea Party members deliberately disrupting the proceedings, rattling some of the politicians enough that they were cancelling public appearances altogether.

It was hard to decide what to make of all this. The Tea Party’s anti-tax, anti-regulation, anti-government manifesto was hardly new; its basic story line—that corrupt liberal élites had hijacked the federal government to take money out of the pockets of hardworking Americans in order to finance welfare patronage and reward corporate cronies—was one that Republican politicians and the conservative media had been peddling for years. Nor, it turned out, was the Tea Party the spontaneous, grassroots movement it purported to be. From the outset, the Koch brothers and affiliates like Americans for Prosperity, along with other billionaire conservatives, had carefully nurtured the movement, providing much of the Tea Party’s financing, infrastructure, and strategic direction.

Still, there was no denying that the Tea Party represented a genuine populist surge within the Republican Party. It was made up of true believers, possessed with the same grassroots enthusiasm and jagged fury we’d seen in Sarah Palin’s supporters during the closing days of the Presidential campaign. Some of that anger I understood, even if I considered it misdirected. Many of the working- and middle-class whites gravitating to the Tea Party had suffered for decades from sluggish wages, rising costs, and the loss of the steady blue-collar work that provided secure retirement. George W. Bush and establishment Republicans hadn’t done anything for them, and the financial crisis had further hollowed out their communities. And so far, at least, the economy had grown steadily worse with me in charge, despite more than a trillion dollars channelled into stimulus spending and bailouts. For those already predisposed toward conservative ideas, the notion that my policies were designed to help others at their expense—that the game was rigged and I was part of the rigging—must have seemed entirely plausible.

I also had a grudging respect for how rapidly Tea Party leaders had mobilized a strong following and managed to dominate the news coverage, using some of the same social-media and grassroots-organizing strategies we had deployed during my own campaign. I’d spent my entire political career promoting civic participation as a cure for much of what ailed our democracy. I could hardly complain, I told myself, just because it was opposition to my agenda that was now spurring such passionate citizen involvement.

As time went on, though, it became hard to ignore some of the more troubling impulses driving the movement. As had been true at Palin rallies, reporters at Tea Party events caught attendees comparing me to animals or Hitler. Signs turned up showing me dressed like an African witch doctor with a bone through my nose. Conspiracy theories abounded: that my health-care bill would set up “death panels” to evaluate whether people deserved treatment, clearing the way for “government-encouraged euthanasia,” or that it would benefit illegal immigrants, in the service of my larger goal of flooding the country with welfare-dependent, reliably Democratic voters. The Tea Party also resurrected an old rumor from the campaign: that I was not only Muslim but had actually been born in Kenya, and was therefore constitutionally barred from serving as President. By September, the question of how much nativism and racism explained the Tea Party’s rise had become a major topic of debate on the cable shows—especially after the former President and lifelong Southerner Jimmy Carter offered up the opinion that the extreme vitriol directed toward me was at least in part spawned by racist views.

At the White House, we made a point of not commenting on any of this—and not just because Axe had reams of data telling us that white voters, including many who supported me, reacted poorly to lectures about race. As a matter of principle, I didn’t believe a President should ever publicly whine about criticism from voters—it’s what you signed up for in taking the job—and I was quick to remind both reporters and friends that my white predecessors had all endured their share of vicious personal attacks and obstructionism.

More practically, I saw no way to sort out people’s motives, especially given that racial attitudes were woven into every aspect of our nation’s history. Did that Tea Party member support “states’ rights” because he genuinely thought it was the best way to promote liberty, or because he continued to resent how federal intervention had led to desegregation and rising Black political power in the South? Did that conservative activist oppose any expansion of the social-welfare state because she believed it sapped individual initiative or because she was convinced that it would benefit only brown people who had just crossed the border? Whatever my instincts might tell me, whatever truths the history books might suggest, I knew I wasn’t going to win over any voters by labelling my opponents racist.

One thing felt certain: a pretty big chunk of the American people, including some of the very folks I was trying to help, didn’t trust a word I said. One night, I watched a news report on a charitable organization called Remote Area Medical, which provided medical services in temporary pop-up clinics around the country, operating out of trailers parked at fairgrounds and arenas. Almost all the patients in the report were white Southerners from places like Tennessee and Georgia—men and women who had jobs but no employer-based insurance or had insurance with deductibles they couldn’t afford. Many had driven hundreds of miles to join crowds of people lined up before dawn to see one of the volunteer doctors, who might pull an infected tooth, diagnose debilitating abdominal pain, or examine a breast lump. The demand was so great that patients who arrived after sunup sometimes got turned away.

I found the story both heartbreaking and maddening, an indictment of a wealthy nation that failed too many of its citizens. And yet I knew that almost every one of those people waiting to see a free doctor came from a deep-red Republican district, the sort of place where opposition to our health-care bill, along with support of the Tea Party, was likely to be strongest. There had been a time—back when I was still a state senator driving around southern Illinois or, later, travelling through rural Iowa during the earliest days of the Presidential campaign—when I could reach such voters. I wasn’t yet well known enough to be the target of caricature, which meant that whatever preconceptions people may have had about a Black guy from Chicago with a foreign name could be dispelled by a simple conversation, a small gesture of kindness.

I wondered if any of that was still possible, now that I lived locked behind gates and guardsmen, my image filtered through Fox News and other media outlets whose entire business model depended on making their audience angry and fearful. I wanted to believe that the ability to connect was still there. My wife wasn’t so sure. One night, Michelle caught a glimpse of a Tea Party rally on TV—with its enraged flag-waving and inflammatory slogans. She seized the remote and turned off the set, her expression hovering somewhere between rage and resignation.

“It’s a trip, isn’t it?” she said.

“What is?”

“That they’re scared of you. Scared of us.” She shook her head and headed for bed.

Ted Kennedy died on August 25th. The morning of his funeral, the skies over Boston darkened, and by the time our flight landed the streets were shrouded in thick sheets of rain. The scene inside the church befitted the largeness of Teddy’s life: the pews packed with former Presidents and heads of state, senators and members of Congress, hundreds of current and former staffers. But the stories told by his children mattered most that day. Patrick Kennedy recalled his father tending to him during crippling asthma attacks. He described how his father would take him out to sail, even in stormy seas. Teddy, Jr., told the story of how, after he’d lost his leg to cancer, his father had insisted they go sledding, trudging with him up a snowy hill, picking him up when he fell, and telling him “there is nothing you can’t do.” Collectively, it was a portrait of a man driven by great appetites and ambitions but also by great loss and doubt—a man making up for things.

“My father believed in redemption,” Teddy, Jr., said. “And he never surrendered, never stopped trying to right wrongs, be they the results of his own failings or of ours.”

I carried those words with me back to Washington, where a spirit of surrender increasingly prevailed—at least, when it came to getting a health-care bill passed. A preliminary report by the Congressional Budget Office, the independent, professionally staffed operation charged with scoring the cost of all federal legislation, priced the initial House version of the health-care bill at an eye-popping one trillion dollars. Although the C.B.O. score would eventually come down as the bill was revised and clarified, the headlines gave opponents a handy stick with which to beat us over the head. Democrats from swing districts were now running scared, convinced that pushing forward with the bill amounted to a suicide mission. Republicans abandoned all pretense of wanting to negotiate, with members of Congress regularly echoing the Tea Party’s claim that I wanted to put Grandma to sleep.

The only upside to all this was that it helped me cure Max Baucus of his obsession with trying to placate Chuck Grassley. In a last-stab Oval Office meeting with the two of them in early September, I listened patiently as Grassley ticked off five new reasons that he still had problems with the latest version of the bill.

“Let me ask you a question, Chuck,” I said finally. “If Max took every one of your latest suggestions, could you support the bill?”

“Well . . .”

“Are there any changes—any at all—that would get us your vote?”

There was an awkward silence before Grassley looked up and met my gaze. “I guess not, Mr. President.”

I guess not.

At the White House, the mood rapidly darkened. Some of my team began asking whether it was time to fold our hand. Rahm was especially dour. Having been to this rodeo before, he understood all too well what my declining poll numbers might mean for the reëlection prospects of swing-district Democrats, many of whom he had personally recruited and helped elect, not to mention my own prospects in 2012. Rahm proposed that we try to cut a deal with Republicans for a significantly scaled-back piece of legislation—perhaps allowing people between sixty and sixty-five to buy into Medicare or widening the reach of the Children’s Health Insurance Program. “It won’t be everything you wanted, Mr. President,” he said. “But it’ll still help a lot of people, and it’ll give us a better chance to make progress on the rest of your agenda.”

Some in the room agreed. Others felt it was too early to give up. Phil Schiliro said he thought there was still a path to passing a comprehensive law with only Democratic votes, but he admitted that it was no sure thing.

“I guess the question for you, Mr. President, is, Do you feel lucky?”

I looked at him. “Where are we, Phil?”

Phil hesitated, wondering if it was a trick question. “The Oval Office?”

“And what’s my name?”

“Barack Obama.”

I smiled. “Barack Hussein Obama. And I’m here with you in the Oval Office. Brother, I always feel lucky.”

I told the team that we were staying the course. But my decision didn’t have much to do with how lucky I felt. Rahm wasn’t wrong about the risks, and perhaps in a different political environment, on a different issue, I might have accepted his advice. On this issue, though, I saw no indication that Republican leaders would throw us a lifeline. We were wounded, their base wanted blood, and, no matter how modest the reform we proposed, they were sure to find a whole new set of reasons for not working with us.

More than that, a scaled-down bill wasn’t going to help millions of people who were desperate. The idea of letting them down—of leaving them to fend for themselves because their President hadn’t been sufficiently brave, skilled, or persuasive to cut through the political noise and get what he knew to be the right thing done—was something I couldn’t stomach.

Knowing we had to try something big to reset the health-care debate, Axe suggested that I deliver a prime-time address before a special joint session of Congress. It was a high-stakes gambit, he explained, used only twice in the past sixteen years, but it would give me a chance to speak directly to millions of viewers. I asked what the other two joint addresses had been about.

“The most recent was when Bush announced the war on terror after 9/11.”

“And the other?”

“Bill Clinton talking about his health-care bill.”

I laughed. “Well, that worked out great, didn’t it?”

Despite the inauspicious precedent, we decided it was worth a shot.

Two days after Labor Day, Michelle and I climbed into the back seat of the Presidential S.U.V., known as the Beast, drove up to the Capitol’s east entrance, and retraced the steps we had taken seven months earlier to the doors of the House chamber, where I’d given my first address to a joint session of Congress, back in February. The mood in the chamber felt different this time—the smiles a little forced, a murmur of tension and doubt in the air. Or maybe it was just that my mood was different. Whatever giddiness or sense of personal triumph I’d felt shortly after taking office had now been burned away, replaced by something sturdier: a determination to see a job through.

For an hour that evening, I explained as straightforwardly as I could what our reform plan would mean for the families who were watching—how it would provide affordable insurance to those who needed it but also give critical protections to those who already had insurance; how it would prevent insurance companies from discriminating against people with preëxisting conditions and eliminate the kind of lifetime limits that burdened families like Laura Klitzka’s. I detailed how the plan would help seniors pay for lifesaving drugs and require insurers to cover routine checkups and preventive care at no extra charge. I explained that the talk about a government takeover and death panels was nonsense, that the legislation wouldn’t add a dime to the deficit, and that the time to make this happen was now. But in the back of my mind was a letter from Ted Kennedy I’d received a few days earlier. He’d written it in May but had instructed Vicki to wait until after his death to pass it along. It was a farewell letter, two pages long, in which he thanked me for taking up the cause of health-care reform, referring to it as “the great unfinished business of our society” and the cause of his life. He added that he would die with some comfort, believing that what he’d spent years working toward would now, under my watch, finally happen.

I ended my speech that night by quoting from Teddy’s letter, hoping that his words would bolster the nation just as they had bolstered me. “What we face,” he’d written, “is above all a moral issue; that at stake are not just the details of policy, but fundamental principles of social justice and the character of our country.”

According to poll data, my address to Congress boosted public support for the health-care bill, at least temporarily. Even more important for our purposes, it seemed to stiffen the spine of wavering congressional Democrats. It did not, however, change the mind of a single Republican in the chamber. This was clear less than thirty minutes into the speech, when—as I debunked the phony claim that the bill would insure undocumented immigrants—a relatively obscure five-term Republican congressman from South Carolina named Joe Wilson leaned forward in his seat, pointed in my direction, and shouted, his face flushed with fury, “You lie!”

For the briefest moment, a stunned silence fell over the chamber. I turned to look for the heckler (as did Speaker Pelosi and Joe Biden, Nancy aghast and Joe shaking his head). I was tempted to exit my perch, make my way down the aisle, and smack the guy in the head. Instead, I simply responded by saying, “It’s not true,” and then carried on with my speech as Democrats hurled boos in Wilson’s direction.

As far as anyone could remember, nothing like that had ever happened before a joint-session address—at least, not in modern times. Congressional criticism was swift and bipartisan, and, by the next morning, Wilson had apologized publicly for the breach of decorum, calling Rahm and asking that his regrets get passed on to me as well. I downplayed the matter, telling a reporter that I appreciated the apology and was a big believer that we all make mistakes.

Excerpt via The New Yorker. Click here to read more.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions