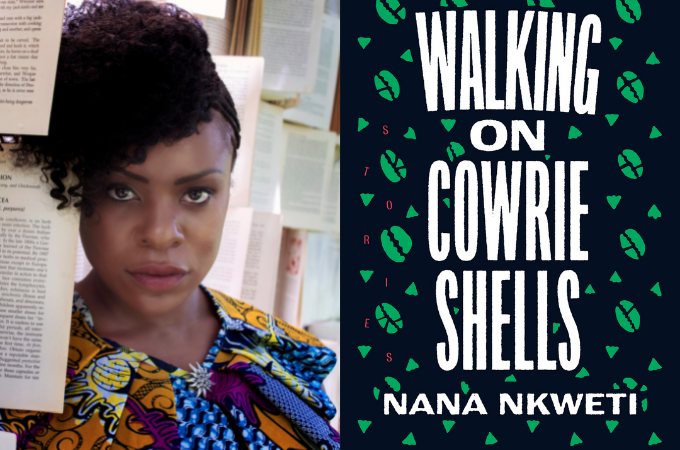

Walking on Cowrie Shells is a delightful read. Nkweti’s writing is a gem. Funny and loaded with turns of phrases, it incites chuckles and some laughs but also tears and wonder.

A Caine Prize finalist, Nkweti is no stranger to the form of the short story. But with this collection, the expansive range of her abilities are put on full display. Through stories that explore faith and family, love and romance, fantasy and mythology, race and violence, Nkweti showcases the rich diversity of the Cameroonian experience set against a global backdrop and channeled through genres that range from from anime comics to zombie apocalypse to mami wata myths.

I find it fascinating that most of the lead characters are women. Whether it’s an entrepreneurial sex worker in “It Takes a Village” or an expectant mother questioning her faith in “The Devil is a Liar,” the women in Walking on Cowrie Shells are captivating in their own unique way. Nkweti doesn’t settle for stereotypes or half-baked characters exploited to move plot along. Every woman in her fictional universe is shown in the full light of her complexity: strengths, flaws, and all. In “Night Becomes Us,” a different writer would have used Hanifa, the suicide bomber, to kill off Zeinab’s mother and quickly moved on to the next plot twist, leaving Hanifa behind to live on in the reader’s imagination as the epitome of evil. But Nkweti interrupts the narrative to provide Hanifa’s backstory. This way the reader understands that Hanifa’s violence originates from other hurts rooted in the founding violence of patriarchy.

In a sense, Walking on Cowrie Shells is a book about women behaving badly and refusing to apologize for their desire to go against the norm. “Raincheck at Momocon” is the love story between Astrid, a Bamenda girl in NYC and Young, a South Korean boy and fellow comic nerd. Their love is innocent but filled with intense longing. The story looks at how Astrid comes to romantic awareness even as she strains under the watchful eyes of her African immigrant parent and all their expectations of success and respectability.

My favorite story is “Dance the Fiya Dance.” A classic girls-at-war story in a world of baby showers, wedding receptions, and funerals. It tells the story of Chambu, a linguistic anthropologist newly moved to Washington DC from NYC. Chambu keeps a diary while navigating the charged terrain of being single and “Akata” in a diaspora Cameroonian world. She is Bridget Jones, but a successful and ambitious version. The story is about Chambu insisting on looking for love on her own terms, but it also offers a glimpse into the rapturous celebration of life in diaspora African communities. The dancing, food laden tables, the gossips, the drinks all point to a world where—whether birth, death, or matrimony is being celebrated—togetherness is the dominant social language.

The story I found most intriguing is “The Living Infinite.” Nala is a mami wata whose life is bound by two water worlds, the mangroves of Doula and the Bayou in Louisana. The link between these worlds is an African American man named Byron. Nala’s ancestry is a long line of nomad women and goddesses who rule the “sandy lagoons and tidal estuaries along Africa’s coastlines.” To the uninitiated eye, Nala is a beautiful woman. But in her true form, she is half human, half fish covered in “indigo-trellised scales.” The story is erotic, not for graphic sexual content, but for the slow burn of desire in fevered caresses and kisses. The story also links global black worlds separated and connected by the Atlantic, the history of violence it bears, and the myths it inspires.

Thinking of African literature more broadly, Nkweti’s collection is significant for the ways it looks at Cameroon through a wide lens. In Nkweti’s diverse and complex story-worlds, the experiences of a Bamenda Girl, an Ngassa woman, a Fula girl, a Bamileke man and many others are used to reflect the many facets of the human story. The way the characters embody their Cameroonian uniqueness so authentically is precisely why they are all so relatable. Nkweti beautifully executes the storyteller’s task of using the particularities of her characters to ask universal questions but life.

***********

Buy Walking on Cowrie Shells: Bookshop

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions