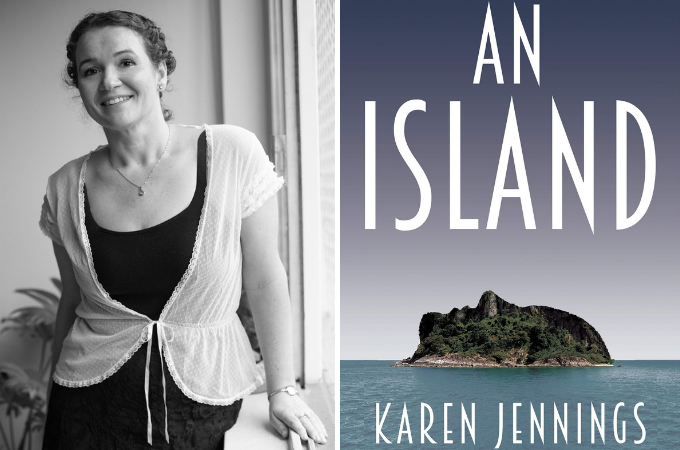

The Booker Prize wields enormous power in the industry. The prize has been known to change the lives of authors. South African novelist Karen Jennings is one such writer.

A few weeks ago, South African writer Karen Jennings thought her novel An Island was a sales flop. It was hard enough to find a publisher for the book, but, as she reveals in an interview with The Guardian, the most frustrating part, was seeing the book completely ignored by critics and readers. She told The Guardian that she felt ashamed, feeling as though she’d failed her publisher. All that changed the day the novel appeared on the Booker longlist. There is nothing more uplifting and heartwarming than the story of a consistently hardworking writer finally getting the recognition they deserve.

This sort of recognition is obviously a game changer; still, Jennings is anything but ‘new’ to literary success. Her earlier body of work consisting of a novel, a memoir and a poetry collection has been met with moderate acclaim within the African continent, and her many honors include a Commonwealth Short Story Prize, a Morland Foundation Scholarship, as well as finalist for the inaugural Etisalat Prize for Literature, which rewards the best debut novel by an African writer, and a Short Story Day Africa Prize.

And yet Jennings latest novel An Island, written with support from the Morland Foundation, suffered many rejections from publishers, including Jennings’ own previous publishers. The rejections had little to do with Jennings’ writing, which has been lauded for its spellbinding simplicity, but more with the subject matter such as race, xenophobia and the question of refugees, which many considered controversial.

In the end, however, the novel was picked by Holland House, a small independent press based in London and a one-person run firm dedicated to finding new voices. In collaboration with Karavan Press, an equally small South African-based press, the slim novel was published in 2020 with just 500 printed copies. Publisher requests for reviews, blurbs and endorsements to help sell the book were overlooked.

On 1 August, the novel was longlisted for the 2021 Booker Prize, pitting Jennings alongside established authors and Booker favorites ranging from previous winner Kazuo Ishiguro to two-time nominee and fellow South African Damon Galgut.

At £50,000, the Booker Prize is considered one of the most prestigious literary honor for a single novel written in English. A keenly coveted award, winners as well as nominees are often guaranteed instant success in terms of publicity and book sales.

The cliche is largely evident for Jennings, who appears to be one of the few relatively “new” names on the Booker Prize list and on the larger UK readership market. Booktubers, following the nominee announcement, have noted that Jennings’ An Island was one of their least expected books, having completely eluded earlier predictions. Jennings’ listing, in essence, came to many as a delightful surprise.

Following her nomination, the novel has benefited from the “Booker effect,” witnessing a spike in demand from readers, such that Holland House, Jennings’ UK publishers, have had to reprint over 5,000 more copies in less than a week, a 1000 percent leap from its earlier print, with two further print runs scheduled, according to a statement on the Booker Prize website. In addition, international rights to the novel have been sold to foreign publishers like Australia’s Text Publishing, as well as some foreign-language rights to countries including Greece.

Jennings admits that she is positively “shocked” by the turn of events. We can imagine. It’s hard not to be, taking into account the fraught journey to publication right from the novel’s completion, and subsequent paltry sales.

The novel, which follows a light keeper’s encounter with a stranded refugee, engages insightful and uncomfortable conversations on race and xenophobia, which might have accounted for the large disinterest in publishing her in South Africa. Another reason too, as suggested by Jennings, might be the seeming weak profitable prospects of the novel. Publishers were concerned that the story, with its many “baggage” might not be an easy sell in the African market.

This unwillingness by major publishers to take risks with new, experimental voices that do not pander to safe stereotypes is a trend that should, in Jennings’ opinion, be done with. “If the publishers are willing to take chances on different kinds of stories and different kinds of writers, then I think the public will, too,” she told The Guardian.

It is for this reason that Jennings continues to use her recently-acquired fame to highlight the work of smaller independent publishers, like Holland House, who have been tremendously impacted negatively by the pandemic.

Jennings’ story is reminiscent of Irish writer Eimear McBride who, after suffering rejections spanning nine years, for her debut novel A Girl is a Half Formed Thing, went on to be published by a new independent small press Galley Beggar and instantly shot to fame, winning a string of competitive literary prizes, including the coveted Women’s Prize in 2014.

How was Jennings able to keep writing in the face of a demoralizing snobbery? Jennings told The Guardian. “I was never motivated by money or success, I’ve always just loved writing. As long as I believed in what I was working on [I kept going]. So it’s not necessarily that I believed in myself, but rather that I believed in the work.”

We are super stoked for Karen Jennings and hope that this is one out of many wins to come.

The shortlist for the Booker Prize will be announced in September and the winner in November.

Jean Meiring August 21, 2021 06:08

This observation does not counter the point about an absence of reviews made in the piece, but adds some more nuance. “An Island” was reviewed in the Afrikaans-language media some months ago, on the shared books page of the three Afrikaans daily papers. The review, by Jonathan Amid, was glowing. Ironically perhaps, the Afrikaans media arguably provides the most consistent coverage of South African writing.