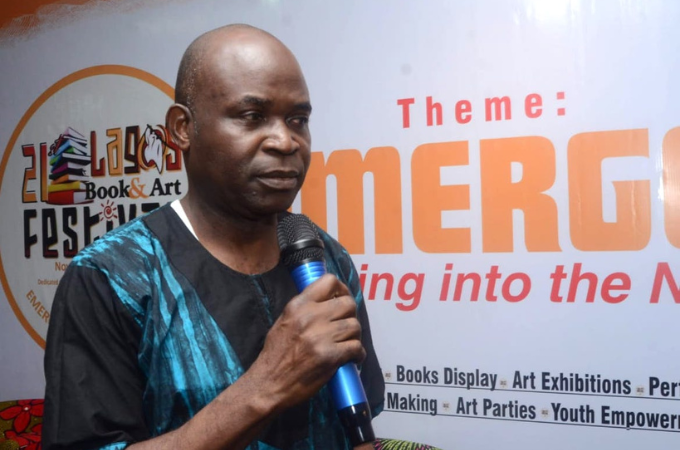

Lagos Book and Art Festival (LABAF) turns twenty-five this year, and Sanya Osha highlights the contributions of one of the co-founders of the event.

***

Jahman Anikulapo is clearly a colossus within artistic circles in Nigeria for the sheer amount of work, dedication and sacrifice he has put in to ensure that contemporary art in the country is visible and well represented. When he embarked on the eventful quest as a ‘culture worker’, many would not have guessed the mild-mannered, unassuming man would have such a transformative impact on how the art world was run and positioned. Jahman came upon the scene quietly but not long after, he established himself as a key player equally at home with artists, foreign cultural centres and a wide variety of government officials working in the culture sector. It is this remarkably smooth ability to veer into different spheres of activity without causing rancour or undue friction that has made him the go-to-guy in all matters of culture in Nigeria.

He worked for many years for The Guardian Newspapers during its golden era under the mentorship of the equally selfless Ben Tomoloju. In 1991, he was drafted by Toyin Akinoso, Yomi Layinka, Tunde Lanipekun and Jossy Ogbuanoh to pen the mission statement of the Committee for Relevant (CORA), a gathering that mediates the gulf between government and the culture sector. Chika Okeke-Agulu – now a professor in the Department of African American Studies, Princeton University – subsequently joined them as a student, and he’s credited as a co-founder. Anikulapo was a reporter when he was enlisted and eventually became a stalwart of the group.

Similarly, the Lagos Book and Art Festival (LABAF) was inaugurated in September 1999 by Akinosho and Anikulapo as National Creativity Day and to welcome Chinua Achebe back home after his automobile accident in 1991 which confined him to a wheel chair for the rest of his life. Thus, for over three decades, LABAF has been at the forefront of promoting Nigerian literary culture internationally.

Anikulapo went on to co-found the iRepresent International Film Festival (iREP) which showcases documentaries – along with Femi Odugbemi and Makin Soyinka in March 2010.

After serving The Guardian Newspapers for twenty-five years he temporarily disengaged from active journalism as the editor of the Sunday edition. Nonetheless, he serves as an advisor and sits on the editorial board of NaijaTimes, an online publication. In addition, he assists as Wole Soyinka’s media assistant. Currently, he’s engaged in a flurry of events to mark Soyinka’s 90th birthday celebrations. His post-Guardian years have largely involved a deeper immersion in theatre and film pursuits either as a resource person, facilitator or organiser of a bewildering range of events. And he’s managed to accomplish all of this without being narcissistic or hogging the spotlight. This almost overwhelming sense of modesty is what grants his varied accomplishments an even keener edge.

Indeed, his names, Jahman Anikulapo, reveal a great deal about his character and values. Jahman, obviously a Rastafarian reference, calls to mind Bob Marley, Peter Tosh and Bunny Wailer, three incontrovertible icons of reggae. These legendary Jamaican musicians not only thrust reggae onto the global stage with their transcendent music but also managed to forge an ethos of selflessness and social commitment. The name Jahman also alludes to a wellspring of spirituality. These values are also central to the sort of practice Jahman was able to evolve.

Anikulapo, on the other hand, immediately evokes another great icon of social and artistic transformation, Fela Anikulapo-Kuti. Anikulapo-Kuti, as we all know, employed music as a weapon. Jahman – originally an indigene of Abeokuta, Anikulapo-Kuti’s hometown – on his part, believes art must strive towards relevance and that a central part of the beauty of art stems from its transformative impact. It is intended that such therapeutic effects would in turn lead to the alleviation of social neuroses. Jahman’s practice is deeply informed by this belief in the restorative powers of culture. In the Southern part of Africa, this kind of belief can be found in the philosophy of ubuntu or in a crudely put aphorism, “we are, therefore, I am.” From Jahman’s vantage point, the communal antecedents of art are important for its reception and appreciation. And so, all through his professional life, he has sought to form collectives that downplay the role of the self-seeking ego in favour of the wisdom and integrity of the communal. How he managed this incredible feat in the cauldron of fiery egotists that Lagos often is can only be imagined. To do so, one can only surmise, must have entailed a sleight of hand involving Zen-like psychosocial engineering.

Many would want to wish Jahman an even more productive final phase after turning 60 last year and having led a focused and well spent life. It is quite apt to say Jahman elicits a lot of admiration for the way in which he has conducted his personal and professional lives. I can recall his conduct and performance during one of my first journalistic assignments to cover an art exhibition at Newton Jibunoh’s Didi Museum on Victoria Island, Lagos in the early 1990s, which were simply delectable. I was a novice journalist and he expertly chaperoned me without even giving a hint of doing so. In other words, he didn’t condescend to me even though there was so much I learnt from him in one evening.

I have never really admired artists doubling as art administrators as the case of some presidents of our art associations (e.g. Performing Musicians Association of Nigeria (PMAN), theatre bodies and literary fraternities have demonstrated. Many of them began as artists and ended up as controversial, fractious and sometimes even mediocre administrators who ended up producing very few pieces of art worth talking about.

Jahman never deceived himself, at least not publicly, about being an artist and instead he concentrated in seeing that the arts and artists are well represented in policy decisions. CORA has become a veritable institution for not only forging a collective voice for Nigerian artists but also honouring the achievements of ageing or pioneer artists who are unfairly ignored in the public eye. In representing appropriately, the achievements of this category of artists, Jahman and his team at CORA are not only paying homage to the entrenched African tradition of according respect to our elders but also exhibiting in the most discreet way, their deep sense of patriotism, dedication and humanity. By adopting this sort of stance, Jahman is affirming that the values inherent in the art of preservation are an integral part of the art-making process.

In this way, among others, he goes against the grain and instead manages to establish a path for those who wish to devote themselves fully to the arts and artists without self-seeking publicity motives. Nigeria definitely needs more of his kind as he ponders what new paths to explore at this stage of his life. He ought to draw comfort from the fact that he has done his best which is better than what most of us have achieved. There is indeed a lot to be thankful for, least of all, Anikulapo’s championing of the cause of the cultural underdog in a context that is paradoxically compromised by ever-growing philistinism.

Image courtesy of Sanya Osha

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions