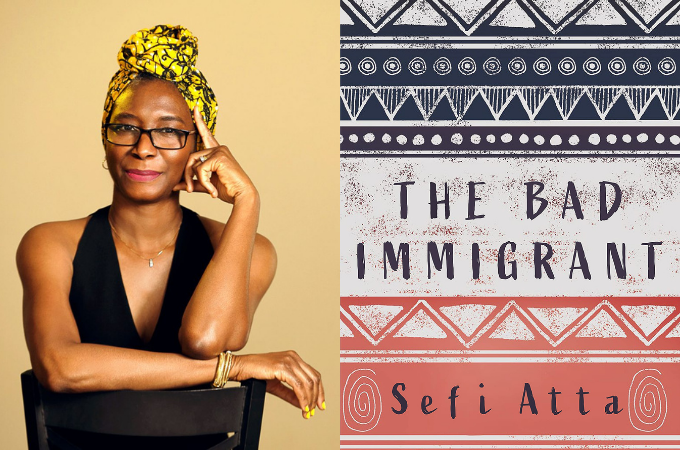

Sefi Atta’s latest novel, The Bad Immigrant, is an engaging work and a sympathetic articulation of what it means to be an African immigrant in today’s America. I met with the Nigerian-American writer to discuss her own transcontinental creative approach to addressing some of the peculiarities of the African diasporic experience, especially the dynamics of racism and capitalism.

***

Daniel Chukwuemeka

Your latest novel, The Bad Immigrant, is a delightful read. I especially enjoyed its narrative flow and sympathetic articulation of the experience of African immigrants in America. As a Nigerian-American writer, I am sure that your readers must be keen on reading about African diasporic experience from your own perspective. So, it would be a great pleasure if you could provide some insight for us.

Let us begin with your main protagonist in The Bad Immigrant. Why did you decide to write about a male immigrant?

Sefi Atta

I have more in common with Lukmon. He has an odd sense of humour, he is a stay-at-home parent and he loves books. Hopefully, writing from a male perspective will stop people from asking why I write from a female one. However, being a woman does influence my views and behavior, as does my background in general, so I do not agree with every opinion Lukmon holds, or approve of everything he says and does in the novel. He experiences what it is like to stay at home and raise kids for a short while, and he does not handle family tensions in ways that I would. In addition, the novel follows him in his first two years in the United States, and I have lived here for twenty-eight years. Consequently, I understand more about race relations here than he does.

Daniel Chukwuemeka

That’s interesting, so then I have to ask, were you not interested in following a female immigrant’s journey in this novel?

Sefi Atta

Not in this novel. Lukmon’s wife, Moriam, was not introspective enough for me to rely on as a protagonist. I have met Nigerians like her in the US and, much as their pragmatism fascinates me, I do not understand their wilful indifference to race relations here.

Daniel Chukwuemeka

That leads me to my next question which is the title of the novel. How did you come to settle on The Bad Immigrant?

Sefi Atta

It sounded just right. I had been working on the novel for many years and it was Made in Nigeria until that phrase became overused, after it was announced as a Nigerian government slogan. You can imagine how irritated I was when I found out.

Daniel Chukwuemeka

Understandably.

Now, literary fictions tend to interweave personal narratives and broader historical contexts. Your 2018 novel, The Bead Collector, for example, does this masterfully by the way it connects the relationship between a Nigerian and an American woman, Remi Lawal and Frances Cooke, to the larger dynamics of instability and uncertainty that trail Nigeria’s insertion into the global community. However, what I find in the case of The Bad Immigrant is the interweaving of personal lives and what I call ‘stereotypical contexts’, whereby other people’s identities are colored with what often appears to be deprecating clichés. For example, a white woman in England tells Lukmon that “liking fat women” is part of Nigerian (men’s) culture. Tell me about how and why you explored stereotypes in the novel.

Sefi Atta

I explore stereotypical views in The Bad Immigrant simply because people have them, and in situations where recent immigrants interact with nationals of their host countries, such views become more apparent. My approach is to satirise them – to show how ridiculous they are. I also interweave Lukmon’s personal narrative and contemporary US history – perhaps not to the extent that I do in The Bead Collector, but my writing style, interests and concerns are present in both novels.

Daniel Chukwuemeka

That interweaving is apparent in instances like when The Bad Immigrant makes references to African immigrants in America, like Ismail, who make excuses for racism and who try to distance themselves from a minoritized identity in the belief that doing so will aid their attempt to class-climb and survive in the American capitalist society. But it also tells about Africans like Osaro, a writer who highlights a contrived, minoritized and oppressed identity in his memoir and official profile in order to successfully negotiate his place in American capitalist hierarchy. What is your aim in presenting these contradictory images of Nigerian immigrants?

Sefi Atta

I am exposing how Nigerian immigrants like Ismail and Osaro take positions on social and political issues, not because they actually support them, but because it benefits them to do so. Osaro tells Lukmon that being a minority can work for him in academia if he knows how to play the game. He champions feminism and LGBTQ rights, even though nothing in his past as an academic in Nigeria suggests that he cares about either of these issues. Meanwhile, Ismail, who works in the financial sector, accuses black people of playing the race card and defends right-wing and even racist opinions that his work colleagues presumably hold. If Osaro is a liberal hypocrite, Ismail is certainly a conservative one because their career ambitions determine the postures they assume. I have met Nigerians like Osaro within African literature circles in the US. It is rare to meet Nigerians like Ismail, but they do exist. I know one or two and I have given up arguing with them. I would say that most Nigerian immigrants are more like Lukmon and Moriam.

Daniel Chukwuemeka

That’s interesting because one of the ways Nigerians in The Bad Immigrant are characterized is by showing how they tend to bring along with them their discriminatory attitudes of tribalism to America. Tell me how you explored the intersection of racism, tribalism and classism. Also, are these –isms possibly connected to gender relations? If yes, how?

Sefi Atta

I created male and female characters from different ethnicities, races and backgrounds. Then I put them in everyday conflict situations and allowed them to communicate with each other. The novel is driven by dialogue – Lukmon’s internal dialogue, in particular – and my readers are eavesdroppers. I wanted to create a fly-on-the-wall experience.

Daniel Chukwuemeka

One such experience includes the listening in on the line: “I was prepared for what racist white people could do, not for what black people could do because of what racist white people had done to them.”

What do you mean by this statement by the protagonist and narrator, Lukmon?

Sefi Atta

The ramifications of racism are wider than Lukmon expects and they complicate relations between African Americans and black immigrants. They do not have to, though, if black immigrants listen, observe, educate themselves and stay honest, as Lukmon does. Regardless, our individual experiences in the US should have no bearing on where we stand on racism. Racism pertains to the collective history and experiences of black people, most of whom in the US are African American.

Daniel Chukwuemeka

Elsewhere the narrator comments on how African immigrants seem to bask in the euphoria of the idea that they are a more successful group than African Americans and thus labeling the latter a lazy demographic. What do you want your readers to understand about these racial labels?

Sefi Atta

My readers are well aware of negative racial labels like this. I mention them just to illustrate how absurd they are, and how dangerous they can be, even to black immigrants who perpetuate them. There is nothing revelatory about the novel in this regard. But writing about racial labels was painful and disturbing because I did not want to offend people who had already been offended more than enough. I had to bring them up, though, in order to tell the story truthfully.

Daniel Chukwuemeka

Building on that, one of the findings of reading The Bad Immigrant is that one has to be ready for racism if they intend to migrate to America. As a “bad immigrant,” the protagonist seems unready to face racism in America. His wife tells him that America is not that bad and reminds him of tribalism back home in Nigeria when he proposes returning to Nigeria. Even though he is the type to give deep thoughts to social issues and sees connections among seemingly unrelated psycho-social phenomena, he believes that racism in America is different from tribalism back in Nigeria. Yet he earlier said that he “was so prepared for being black in America.”

Some may argue that these mental vacillations seem to result in a protracted sense of liminality, alienation, ambivalence, and unrootedness common in diasporic African literature, whereby the African immigrant does not belong to the white nor black American divide of racism and yet must negotiate the two racial divides if they must continue to extricate themselves from the postcolonial marginality and effects of tribalism they left behind in Nigeria. How do you harness these racial and tribal tropes and their attendant contradictions in relation to how they inaugurate a sense of homelessness in your writing?

Sefi Atta

There is a tendency, in the US, to expect certain conditions attributable to the displacement of immigrant characters in stories. But the “I belong to two worlds and I don’t fit in anywhere” narrative has been done many times before, to the extent that it has become formulaic, if not propagandistic, as Lukmon says. I was not interested in writing a novel like that. I also do not trust stories that depict immigrants as faultless people who are incapable of being prejudiced, so I wrote a story that I believed was authentic.

Tribalism, to quote Lukmon, begins with rivalries, the histories of which are distorted over time, whereas racism begins with falsehoods, invented from the outset. His experience is fairly common for Nigerian immigrants in the US. We arrive here with prejudices from our country and the longer we live here, the more we learn about the workings and peculiarities of race relations – if we are willing to.

Lukmon was not ambivalent about where he stood in the US. He said he was relieved to be black. He also stated, when he began to work as a security guard, that he was well prepared for racism from white people. He then later found himself in a dilemma when he detained an African American man who was suspected of stealing, only to find out the man was not only innocent but a lawyer. The incident may have shaken Lukmon for a day or two, but he remained resolute.

Now, it is true that he was in a state of transition that lasted two years and that he felt alienated at times, even from his own family, but The Bad Immigrant is not a novel about an immigrant who lacks agency. In fact, Lukmon calls protagonists like that pathetic. He is firmly rooted in progressive aspects of Yoruba culture, and he has no patience for Nigerian immigrants who are not like him.

Daniel Chukwuemeka

Taking a slightly different focus now, you have been publishing most of your works with Interlink Books. Since 2005 actually, an excellent publishing company, I must add. Tell me about your experience publishing with Interlink. Have you thought about working with other publishers? Why or why not?

Sefi Atta

Interlink Books publishes everything I submit to them. That does not happen for most writers and I consider myself lucky in that respect. I need editorial support, as writers do, but I would never be able to work with a publisher who tries to control my creative expression. Interlink does not do that.

Daniel Chukwuemeka

The narrator of The Bad Immigrant suggests that publishers could be complicit in encouraging certain Afropessimist kinds of writing that seems to aim at “entertaining” the Western reader’s quest for exoticism. Do you see this as instigating a conversation about the current tendency among western publishers and literary prize platforms to privilege a select group of African diasporic writers over their home-based counterparts?

Sefi Atta

No, because the conversation is not new. It has been going on long before I ever published my first novel and it still continues. The Bad Immigrant is, among other things, a tribute to the previous generation of African writers, who started the conversation.

Daniel Chukwuemeka

You divide your time among Nigeria, the United States and England. One cannot help but notice the way in which most of your stories revolve around these three settings, with some of them, including the latest, The Bad Immigrant, chronicling characters whose lives simultaneously circle around these three places. To what extent can you say that your life and work in these countries may have influenced your writing?

Sefi Atta

Perhaps my tri-continental experience has inspired me to retrace my steps. From a practical point of view, however, living in these countries has definitely given me a familiarity with them that shows up in my stories.

Daniel Chukwuemeka

Talking about your other stories, you recently worked with Kunle Afolayan to convert your 2008 novel, Swallow, to a film script for Netflix. What was the experience of converting your creative prose to a dialogic script like? Do you think that the movie version did justice to the original prose?

Sefi Atta

Well, I have written a few screenplays, one of which was a finalist for the American Zoetrope Screenplay Competition in 2019. Swallow was my first adaptation and it was hard work and fun. Kunle and I had to leave a lot out of the story so he could make a two-hour feature film. He also made changes to the final draft, as directors do. Anyone who expects the film to do justice to the original prose will probably be disappointed.

Daniel Chukwuemeka

Do you envisage The Bad Immigrant being made into a movie someday? Essentially, do you think that literary works should be left alone and that making them into a movie may reduce their critical acclaim, especially since the two creative processes require different forms of artistic representation? And what can you say informs the decision by creative entrepreneurs to pick up some literary writings and make them into a movie while seemingly neglecting others?

Sefi Atta

Look, most literary writings – and writers – are neglected in some way and what works for me is this: I ignore those who ignore me; I do not follow what my peers are doing, unless someone informs me about them; I do not read harmful reviews; and I keep producing work. My writing life has been a series of unexpected opportunities, to which I have either said yes or no. That is all I will say.

Daniel Chukwuemeka

Well, thank you for taking the time for this interview, and for shedding so much light on this fantastic new book.

Seffi Atta’s The Bad Immigrant is available since its release in November 2021.

Ugochukwu Anadị March 20, 2022 01:13

Both the interviewer and the interviewee are brilliant people and one can't miss such brilliance, an honest type of brilliance, reading this interview. Nice one.