In a few days, on July 4th, the 17th winner of the Caine Prize for African Writing will be unveiled.

You’ve either read the shortlisted stories or read the reviews we posted right here on Brittle Paper. You have a sense of what the stories are about. You know whether you like them or not. You have your favorites, who you’d like to win, and so on. Well, it’s now time to shift focus from the stories to the brilliant minds that concocted them.

We knew this time would come, so while you were getting acquainted with the stories, we were busy interviewing each of the shortlisted authors. We wanted you to see a side of these writers that you didn’t get from reading their stories. Here is the final interview in the series of five. We would like to thank Nairobi-based writer Akati Khasiani for fielding the questions.

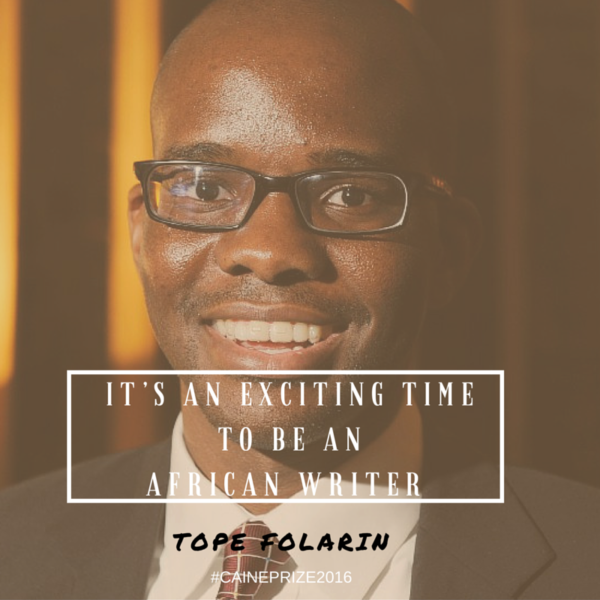

Tope Folarin whose interview is featured today, was born in Nigeria. He is the 2013 winner of the Caine Prize and was named alongside Chimamanda Adichie and Taiye Selasi in the Africa39 list. He lives in Washington, DC.

His shortlisted story is titled “Genesis.” Kola Tubosun who reviewed the story explored the non-fictional dimensions of the story, calling it a “triumphant account” with an “ending so satisfying and so public.” [read here if you missed it]

Enjoy reading!

***

Congrats on making the Caine Prize shortlist. How is being shortlisted significant for you?

Thanks so much. I think the Caine Prize is the best short story competition in the world, so it’s an honor to be shortlisted once again.

The prize is awarded for outstanding “African writing.” We are curious about what ‘African writing’ means to you? Let’s be the first to agree with you that it is an old and tired question. But we are hoping that you’ll humour us and take it as a chance to reflect on the modifier “African” and, perhaps, its place within your work and your sense of yourself as a writer.

Both of my parents were born and raised in Nigeria. Like countless immigrants, they came to America to find better opportunities. My siblings and I were raised with a deep respect for Nigeria, for Africa, and we were all eager to visit Nigeria, but we could not because my parents lacked the funds.

I think my writing reflects both of these aspects of my life—a sense of closeness to Nigeria, and a distance as well.

What’s most important to you in the crafting process? The theme/subject/topic of the story or the form/experimentation/aesthetics of storytelling?

It depends on the story. But generally I think about fiction in terms of form and experimentation and aesthetics. In “Genesis,” for example, I wanted to depict a character who falls into memory as he’s telling the story. This inspired a craft question—how do I move back and forth in time? How can I create a story in which the storyteller becomes lost in the story he’s telling? Eventually I decided that the best way to do this was to manipulate tense (switch from past to present and back again). I spent a fair amount of time thinking about how to do this without distracting the reader.

As I was writing the story I also spent a great deal of time thinking about how the stories we are told about ourselves affect our trajectories. For example, there are two stories in the biblical Genesis that have been used by some to explain why certain people have dark skin. One story says that Noah cursed the descendants of his son Ham because Ham happened to see Noah naked. The evidence of this curse was dark skin. Another story—and I heard this story a few times when I was growing up—says that black people are the descendants of Cain, who was “marked” by God after killing his brother Abel and lying to God about it. The first story was often used to justify slavery in the United States, and in Utah, where I grew up, every now and then I heard a Mormon citing the second story as proof of the inferiority of black people. I reference both stories in “Genesis”—the Cain story is referenced in the first and last scenes of my story, and the Ham story is referenced in the scene where the boys see their father cowering on the floor, naked, after their mother has beat him (it isn’t a coincidence that the protagonist becomes aware of his skin color in the subsequent scene).

In my experience, immigrants are fairly adept at providing their children with certain material essentials—food, water, clothes and the like—and perhaps less adept at helping their children navigate the psychological terrain of the new country. This is to be expected—the immigrant doesn’t know the local stories, and how these stories affect behavior, how they shape destiny. In “Genesis,” when the narrator tells his father what he is hearing from the outside world about his skin and his destiny, his father reacts as any immigrant would—he essentially tells his son to believe in himself, to ignore what he hears. The narrator’s mother realizes he needs more. She provides him with something more in the final scene.

This year’s stories all featured characters dealing with pain in some way, whether a personal trauma or a form of societal or generational suffering. How would you account for this emphasis on suffering—given the criticism that African writing only gets consumed by a global audience when it deals with negative tropes?

That criticism might be true, but I think what you’re describing has more to do with the nature of artistic competition. Think about the Oscars, the BAFTAs, Cannes—the films that perform well at these competitions tend to be dramas. The same holds true for literary competitions.

Are these the same brother and father we met in Miracle? Is “Genesis,” as the title suggests, an earlier part of their story?

Yes, it’s the same family. And yes, “Genesis” is an earlier part of the story.

Do you find a child’s perspective to be a particularly powerful element of fiction? In other words, what do you see and hear through a child that may be blocked off from the point of view of an adult?

The reason why I think employing a child’s perspective in fiction can be especially powerful is that children aren’t really committed to the idea that there is a strict line of demarcation between the real and the imagined.

But what happens when this childish perspective persists into adulthood? That’s one of the questions I was attempting to explore in “Genesis.” In my story, both adults enter America with a set of dreams. The father abandons his dreams (he stows his cowboy hat under his bed) and embraces the practicalities of life in America, and the mother doesn’t, or isn’t able to. If you are a dreamer, and you arrive in a land of dreams, and all the dreams you encounter aren’t really for you, how will this affect you? In “Genesis,” just before the mother and children are taken to the women’s shelter, the mother goes to her bedroom and returns with her husband’s cowboy hat and her records. She’s trying to start again, to hold on her dream.

There are a number of references to popular culture throughout the story, my favorite being the description of a WWE fight. Are the musicians and shows you mention special to you in some way? What led to your including them?

Well, I think pop culture references help to ground a piece of fiction in a particular time and place. I’m also obsessed with pop culture, so that stuff always manages to find its way into my work.

As it happens, I was a major fan of professional wrestling when I was a child (I still am to a certain extent). A child accepts wrestling on its terms. In the ring, the hero can overcome impossible odds. The hero can vanquish the most fearsome opponent. The hero can die and then return to life.

By embedding this scene in my story I am attempting to argue for the power of fiction. Fiction, though it isn’t ‘real’ (just as wrestling isn’t ‘real’), has the power to affect reality. To alter reality. Fiction integrates the imaginary and the impossible into our daily lives. In my story, the protagonist watches Hulk Hogan recover from certain defeat by raising his hand to the sky. Some mysterious power enters his body and enables Hulk to win. My protagonist, who has suffered a number of defeats by this point in the story, raises his own hand to the sky. Maybe one day the power will enter his body.

You are a returning champion. Congrats on being nominated a second time. There is a lot of surprise and talk about the repeat nomination. Any thoughts?

Thank you. I feel incredibly blessed.

Finally, what was your favourite of the other stories?

I really like each of them. It’s an exciting time to be an African writer.

Thanks to Folarin for taking the time out to respond to these questions. We wish him all the best!

Click here to read more of the #caineprize2016 interviews and here to read the reviews.

***************

About the Interviewer:

Akati Khasiani is a city-bred, country-loving, Kenyan writer, doctor and soon-to-be economist with opinions and a tendency to daydream. Her work was featured in the Jalada 01 anthology.

Akati Khasiani is a city-bred, country-loving, Kenyan writer, doctor and soon-to-be economist with opinions and a tendency to daydream. Her work was featured in the Jalada 01 anthology.

Aggretsuko cheats August 23, 2020 02:49

What's Going down i'm new to this, I stumbled upon this I've discovered It positively helpful and it has helped me out loads. I am hoping to contribute & aid different users like its helped me. Good job.