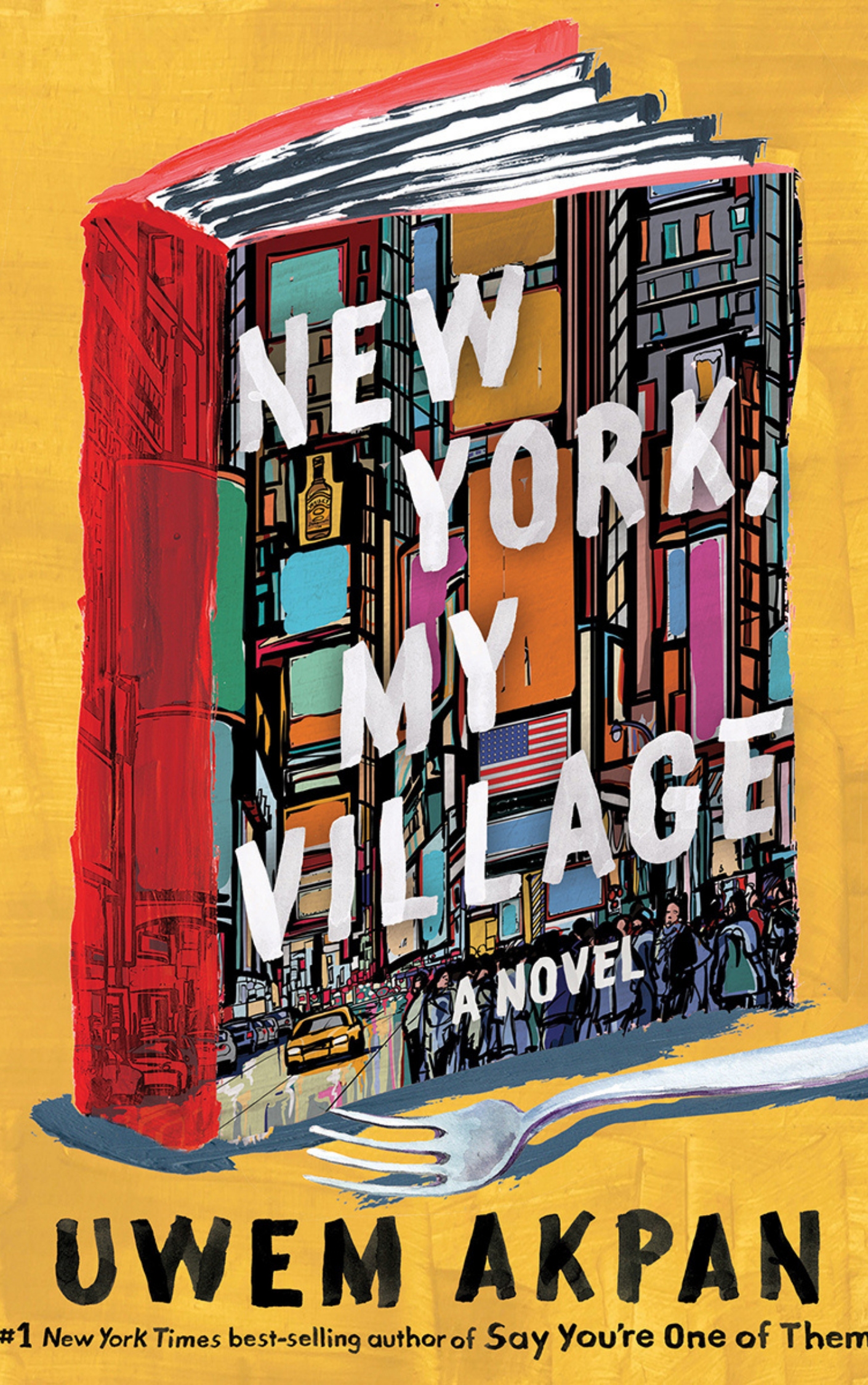

New York, My Village is Uwem Akpan’s debut novel and comes fourteen years after his first book’s groundbreaking success. Say You Are One of Them, which has become a modern classic, is a collection of heartrending stories set in diverse cities in Africa. It received global acclaim, including a selection for Oprah Book Club. The new book is quite different. It tells a moving story about the delights and traumas of coming to America for the first time as an African. But it is also a story about war and the politics of memory.

The novel is doing a lot, juggling several major themes, two historical periods, transcontinental settings, in addition to a large ensemble of characters. But, all these strands come together around the main character, Ekong, a Nigerian editor on a short trip to New York City. Ekong is of the Annang ethnic group located in what is called the south-south region of Nigeria. In some of the opening scenes, we learn that the Annang is a small ethnic group—so small that the US embassy refused Ekong visa on the accusation that he had invented a fake ethnicity. His attempt to get a visa quickly becomes a nightmarish experience of insults, condescension, and rejection simply because of his ethnicity. But, after the humiliating embassy hurdles, Ekong arrives in New York City for a stint at a high-profile publishing house while editing an anthology of stories about the Biafran war, as told from the perspective of the Annang people. As he digs deeper into the unspeakable trauma his people faced in the hands of the Biafran soldiers and the Nigerian army, Ekong realizes that to be a minority is to have your trauma erased from national memory.

The novel expands the lens on the history of the Biafran war. With this book, Akpan joins the chorus of writers documenting the Nigerian civil war, which began in 1967. It has been fifty years since the war ended, and like all events of national significance, people remember it differently. The official narratives tend to stage the war as an epic battle between the newly formed Biafra and Nigeria, which, when viewed through the lens of ethnicity, corresponds to Igbo, on the one hand, Hausa and Yoruba, on the other. But, if Nigeria is a nation of myriad ethnicities, where do these other collectives fit in this binary? How did they experience the war? This is precisely what New York, My Village tries to grapple with. Akpan shifts the focus of his war story from the Biafran and Nigerian accounts to minority communities caught in the middle of the conflict.

Another fascinating addition of this novel to the literary representation of the Nigerian civil war is its focus on second generation survivors. Ekong’s mother is pregnant with him at the time of the war, so he comes of age long after the conflict. We see Ekong dig through layers of history and intimate memories to fashion his own understanding of the war. Reading this novel gives us a glimpse into how younger Nigerians are making sense of a war that they did not experience directly but that continues to frame their lives. Apkan’s work is unique in the way it addresses the experiences of the descendants of those who lived through the war, how they grapple with lingering traumas, as well as deal with the silences and competing narratives around the war. For tackling these questions and offering a different facet of the Biafran War, New York, My Village pairs brilliantly with Adichie’s Half of a Yellow Sun and Chinua Achebe’s There Was a Country.

Though Akpan deals with difficult subjects—war, violence, tribalism, racism—he makes room for humor. New York, My Village is a truly funny book. When Ekong turns his anthropological gaze on New York City, you erupt with laughter. He has ideas about Starbucks, Time Square, New York City apartment culture, American passive-aggressiveness, landlords, bed bugs, and more. This humor comes in handy, especially, when Akpan sets out to expose the dark underbelly of the New York city publishing scene. What Ekong reveals about agents, editors, and the sales department runs the gamut of laugh-out-loud funny to hilariously cringe-worthy moments. In several jaw-dropping scenes, we see editors using progressive rhetoric to mask racism, favoritism, and elitism. As a novelist, Akpan takes the mirror to his industry and brings some of its concerning aspects to light.

New York, My Village is passionate plea that we always think about those who are excluded in our recounting of the past, especially when it has to do with confronting collective traumas in the present.

**************

Buy New York, My Village: Amazon | Bookshop.org

Frank Abumere April 20, 2022 21:51

It is not controversial to assert that New York, My Village is more than a work of fiction. Among other things, it traces the trajectory of othering mostly in Nigeria and the United States of America. It reveals why the past and the present converged, and why the future is unlikely to diverge from both the past and the present. Minorities are usually at the receiving end of the atrocities of othering. The Nigerian Civil War and racism in the United States of America prompt us to ask, why are minorities usually at the receiving end of the atrocities of othering or what is it about minorities that make them the targets of othering? To answer the above question satisfactorily, it is helpful to read Uwem Akpan’s book. More importantly, I encourage everyone, whether a White person in North America, South America or Europe, a Fulani in Nigeria or an Igbo in Eastern Nigeria, to be open minded when reading the book.