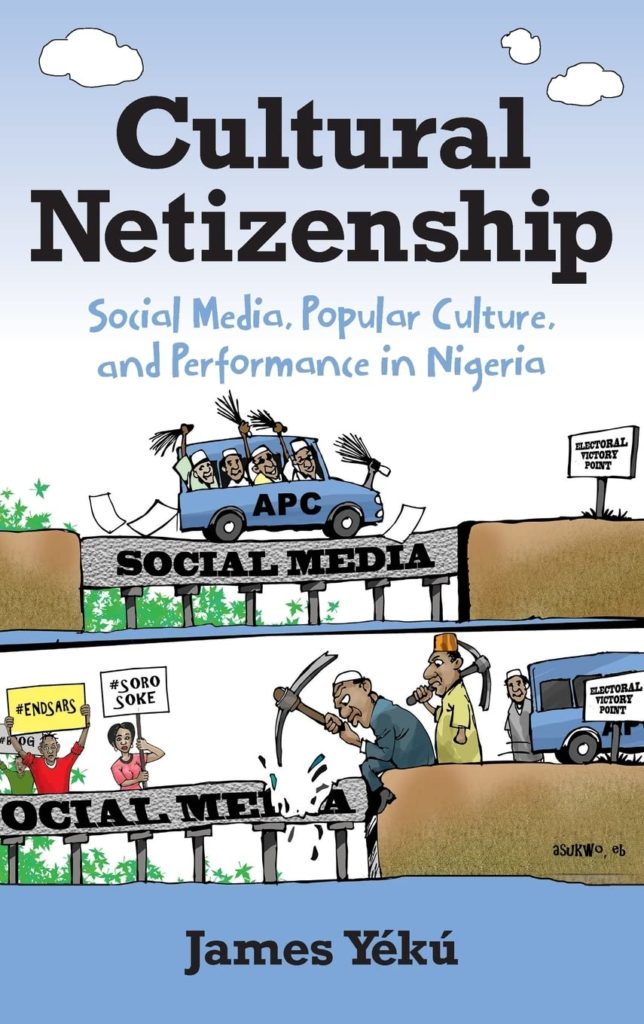

Introduction

Cultural Netizenship and Viral Practices

In July 2020, Nigerian social media comedian MC Edo Pikin (Gbadamosi Agbonjor Jonathan) posted the video “The Difference between Corona and Ebola” on YouTube, outlining in a rather melodramatic language the commonalities and divergences of Covid-19 and the Ebola outbreak of 2014.1 In the narrative, a fictional health expert elaborates on both infections but adds that in Nigeria, the worst of all viruses is government: “When Coronavirus got to the airport and saw the Nigerian government,” the mask-wearing health official says, the virus realized there was no need to enter the country “since their senior colleagues are here already.” He reckons that if some “viruses are infected while some are elected,”2 the most substantial public-health problem in contemporary Nigeria is failed political leadership. While pandemic humor in this text emerges as a mode of deconstructing the identity of the Nigerian state, it is also a means of questioning power that imagines state actors as agents of political pathologies and economic corruption. In the tradition of gallows humor, adversarial circumstances become the means of the text’s antistatist critique of political abjection in Nigeria. As the virality of digital media con- tent such as this overlapped globally with a viral pandemic, the idea that post- colonial Nigeria is plagued by a scourge that infects the body politic through the virus of poor leadership and bad governance warrants an epidemiological reading of state failure that I undertake in sections of this book.

Another viral moment, #EndSARS, presents a similar toxic encounter between the Nigerian state and its citizens. In October 2020, weeks after a summer of demonstrations around the world because of the brutal killing of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer, Nigeria also witnessed a significant youth-led protest against police brutality. Organized around the hashtag #EndSARS, this protest was aimed at the Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS), a notorious unit of the Nigerian Police that was later disbanded because of this nationwide outcry. But #EndSARS also underscores the social circulations and discursive meanings associated with technologies, as SARS, under the guise of fighting internet crime, had been targeting anyone who carried a laptop, an iPhone, or any other media object that signalled digital connectivity. Although #EndSARS was an organic and leaderless movement like other online social movements around the world, it was also a celebrity-driven protest that relied on the voices and coordinating labors of popular entertainers from the culture industry in Nigeria. One of the notable faces during #EndSARS, for instance, was Nigerian rapper Folarin Falana (stage name Falz), who is known for a tradition of protest music that has historically played a role in popular resistance in Nigeria and who has been invited by foreign media like CNN to comment on the movement. There were also other entertainers, such as Instagram comedian @MrMacaroni1 (Debo Adebayo), whose online comic texts, like those of other social media comedians, offer solid representations of the police culture of brutality that activated what was an impending outcry. In the wake of #EndSARS, the TikTok, Instagram, and Twitter accounts of these popular entertainers became repositories of visual narratives documenting the memory of state subjugation and challenging the atrocities of a police institution that consistently displays the most brutal face of the Nigerian state. Their social media timelines and handles became an archive of images and memes that, together with smartphone-camera recordings, questioned the politics that makes state violence the normative reality in Nigeria.

As #EndSARS eventually morphed into a symbolic movement against a gerontocratic culture of perpetual corruption and political excess, @MrMacaroni1 and many others converged on the streets of Lagos to make explicit connections between their digital activism and nondigital spaces of protest. Like MC Edo Pikin’s, @MrMacaroni1 created comic sketches that served as meta-narratives and real-time commentaries on an unfolding moment of youth activism online. Although the social logic that routinely engenders movements such as #EndSARS and the earlier #BringBackOurGirls and #OccupyNigeria is widely and analytically adumbrated, not many scholarly perspectives exist on the online popular culture texts and artistic practices that are produced and circulated on the social web to supplement and invigorate the expressions of activist speech and performances by Nigerian digital subjects. These artistic performances and technology-based expressions of counterhegemonic speech by everyday netizens are my focus in this book. I take seriously the digitally convivial and examine how various forms of visual popular culture produced and distributed on social media serve as the performative idiom that interpellates as cultural netizens those who routinely integrate memes and artistic images of popular culture into performances and narratives of selves on the internet. I am interested in the ways in which social media congeals the production of new imaginative expressions and digital genres that shape and are shaped by a repressive postcolonial state through a process that may be called cultural netizenship.

To be clear, social media platforms are rife with hierarchies and hegemonic tensions, as capital is the primal logic of the social web’s ontological claim to connective relations. Whether a book on social media is relevant in an era in which the dominant narratives of the social web conjure our vulnerability to algorithmic violence and the dystopic promise of a machinic apocalypse will remain subject to ideological contestations for a long time. From the initial enthusiastic celebration of social media and its democratizing impulses, to complaints about its capacity for misinformation and performative narcissism, to threats to delete Facebook after every report of a data breach or privacy violation, our narratives of social media seem to be in constant flux, although a particular account appears to be dominant at a given time. In a pandemic era, we have mainly extolled digital media for enabling the continuation of life and labor, but we have also had to deal with Zoom fatigue, the simultaneous para- dox of being both connected and alienated, and the realization that a digital divide also exists in developed economies.

Ambivalence has always, therefore, haunted narratives of technology, and it is the same with social media. Cultural netizenship allows me to focus on how vernacular contexts transform our relations to technology and the stories that both condition it and, more importantly, are conditioned by it. Simply put, this book is about social media–based cultural productions that serve as the visual repertoire for self-performances and activist speech in Nigeria. The understand- able distrust of social media and its emancipatory promises sometimes obfuscate the ways in which digital audiences in many African countries creatively interact with social media in innovative ways that increase their disruptive visibility in spaces of oppressive power. Despite the power dynamics encoded into the design and use of social media, there is room for subversions, particularly in popular culture. Besides, the dialectical tensions between popular culture and public spaces in Africa today cannot be adequately understood without critical attention to social media and its performative and theatrical possibilities.

As popular imaginings of power crystalize online, cultural netizenship emerges as the enunciation of the dissenting vernaculars of everyday digital subjects. Through critical-cultural approaches that explicate cultural netizenship as the creative space for the articulation of marginal voices on social media, I focus on the nature of African popular culture and performance practices in the age of social media as used in Nigeria. These popular articulations of symbolic forms on social media constitute a huge domain of cultural production in Nigerian digital lifeworlds and manifest new understandings of social, political, and cultural life in the country. I explore everyday encounters with and participation in cultural netizenship as a performative process activated by the social web’s spaces of cultural and political expressions. Cultural netizenship proceeds from practices of remediation in which older media forms and narratives supply visual materials for both performative activism on social media and the articulation of comedic voices in commentary discourses. The basis of a culturalist approach to expressions of citizenship and public speech online is the politicization of popular images in a country with limited opportunities for civic redress and participatory politics. Online images, as anodyne representations or not, show important cultural and political performances that solidify cultural netizenship. As a form of self-making online, cultural netizenship stages the convergence of popular culture and the performance of citizenship in a social media realm not without its political and neoliberal contradictions. I attend to the implications of locally situated understandings of a globally used media form in the context of performances as digital self-presentations of popular culture deployed visually to engage with hegemonic power structures.

Popular culture, as a creative site of urban and non-elite aesthetics on social media, presents digital subjects with opportunities to refigure and contest state power through forms such as humor. The prolific use of mostly nonliterary texts like political cartoons, reaction GIFs, internet memes, selfies, and short humor clips demonstrates an invigoration of popular culture production as an imaginative response to the adversarial inhibitions of the postcolonial state in Africa. As Achille Mbembe argues in his influential On the Postcolony, the post- colony reveals a “dramatic stage” on which are played out the wider problems of subjection and domination (Mbembe 2001, 103). For this reason, cultural netizenship is analytically suited to making sense of the postcolonial state, even more so as more African postcolonial subjects become digitally connected. By centering social media and its visual topographies of amplified popular speech as lenses to understand the protracted dynamics of nation-building and state power, what becomes evident are the visual performances of citizens using humorous commentaries and playful self-presentations to negotiate power and abject conditions.

As social media in Nigeria stages a remarkable explosion of new popular art forms and digital genres, my analysis focuses on the everyday digital culture of netizens, with netizens understood as the proverbial citizens of the internet. The ways a relatively new medium emphasizes the functioning of the visual idioms of online popular culture in the framework of Nigerian social and cultural landscapes are unprecedented and have not really been discussed in any significant full-length volume. I address, therefore, an urgent need for scholarly understandings of how social media facilitates new encounters between the postcolonial state and the many ordinary citizens creating and disseminating new forms of popular culture online. As African cultural forms are increasingly being produced on social media, they mark the cultural significance of the internet as a “domain of the unregulatable” that has become “increasingly central to popular culture as more and more become connected” (Barber 2018, 142). This digital expansion of popular arts provokes the need for a systematic study that captures the new expressions and domains of African popular culture being produced because of the creative and cultural opportunities of social media. Unlike Karin Barber’s proposition, the very structure of the internet suggests it is anything but an “unregulatable” domain—except, of course, if “unregulatable” specifies the internet’s incoherence and messiness for expressions of agency and voice, which are simultaneously bound up with articulations of cultural netizenship itself.

***

Buy Cultural Netizenship: Amazon

Excerpt from CULTURAL NETIZENSHIP: SOCIAL MEDIA, POPULAR CULTURE, AND PERFORMANCE IN NIGERIA by James Yékú, published by Indiana University Press. Copyright © 2022 by James Yékú.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions