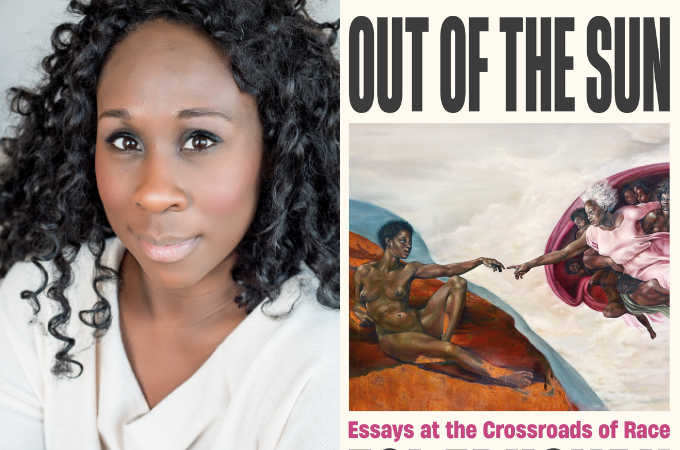

Out of the Sun: On Race and Storytelling by Esi Edugyan is a collection of essays about art, literature, and film. It was aired on the radio as part of CBC Massey Lectures and published last year in print by House of Anansi, an indie press in Canada.

Each of the five chapters are centered on Europe, Canada, America, Africa, and Asia, respectively. In each of the essays, Edugyan links blackness to questions about art and history. From the representation of black people in 19th century European portraiture, the Zambian space mission in the 1960s, the life of 16th century black samurai Yasuke, to the complexities of Rachel Dolezal’s aspiration to racial transformation, Edugyan looks at the representations of black life, bodies, and worlds in an exploration spanning centuries and continents.

The fourth chapter titled “Africa and the Art of the Future” stood out to me. Edugyan revisits afrofuturism, asking why it matters that artists imagine black people in the future. Thinking through Nnedi Okorafor’s work and films like Black Panther and District 9, Edugyan makes the case that stories about the future are important. They open up an experimental spaces where we can examine what went wrong in the past while imagining ways to repair the damage caused by these wrongs.

One of the most insightful moments in the essay is her treatment of Edward Nkoloso and his founding of Zambia National Academy of Science, Space Research and Philosophy in 1960. It was no ordinary space program. Nkoloso planned on sending 2 space cats and a 17 year old girl to the moon and possibly mars. Training for space travel involved rolling downhill in oil drums and oscillating on tire swings. Nkoloso’s space project gained the attention of the world. Western media thought he was delusional. Zambian government officials claimed it was an elaborate joke. Over the decades, critics have offered various explanations, most recently, the Zambian novelist Namwali Serpell in this New Yorker piece. Nkoloso was clearly an eccentric, but Edugyan is kind and attentive in her account of the man’s life and the community he built around his admittedly grandiose dream. Though she touches on the debates around the project and the various attempts to explain why Nkoloso nurtured this strange dream, she wanted to move beyond the sense of bewilderment around Nkoloso. She digs deeper into the underlying significance of Nkoloso’s dream. The mere fact that Nkoloso dared to dream of a future in which an African nation landed in mars and established a civilization is empowering. Ultimately, she does a fantastic job of using Nkoloso’s idea of a future in which Africans are far ahead of the USSR and the US in the space race to think about the politics of dreaming. Our speculation of what tomorrow might be defines us as much as our present experiences. Whether Nkoloso believed in his program or staged it as a satire, he has succeeded in giving us one way to imagine a future centered on blackness. Nkoloso yearned for the “knowledge that would allow [him] to imagine a new future, one powerfully African, and in that very act of creation reimagine a past from what has been suppressed.”

In the essay, Edugyan presents one of the clearest takes I have seen about the importance of art in this task of re-constructing the past in imagined futures. She argues that a film like Black Panther and a novel such as Lagoon offer the imaginative freedom of creating futuristic black worlds. But they do this against the backdrop of a black history darkened by slavery and colonialism. By linking the history of violence in the black experience with the possibility of liberation in stories about the future, she shows that sci-fi is a deeply politically-salient genre. The trope of invasion and abduction in many sci-fi stories evoke colonialism and slavery, two events that loom over black history. But these stories also open the imaginative space for rewriting that history. “Afrofuturism is the story of dislocation,” Edugyan writes, “but it is also the story of recovery, of finding new anchors. Once the past has been extinguished, a future based on its memory is not only the path forward but a commemoration.”

The other chapters offer similarly deep, graceful dives into art, blackness, and history. Out of the Sun is a well-researched, well-written book with lots of new insights about old classics as well as contemporary trends. One of the strengths of the essays comes from the global scale of Edugyan’s life and experience. She is a Canadian author of Ghanaian descent, who has literally traveled the world. She really does bring a transcontinental vision to her examination of blackness as it has been represent across time and space. She interweaves observations about her travels, details about her personal life, her parents, her life in Canada, her struggle with loss and grief, and many intimate moments that adds a private layer to essays that take us through politics, race, art history, and so on. Whether she is writing about Europe or Asia, everything feels close, personal, and urgent.

**********

Buy Out of the Sun: Amazon

**********

Photo by Tamara Poppitt via Lyceum Agency.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions