This must be what death is like, what else could it be? Waking up groggy on a day when the sun is slow to rise. Slowly, ever so slowly, stretching, extracting oneself from the warm covers like a snail emerging from its shell. Tentatively reaching for the floor with one foot and then the other, the damp feel of bare boards. Feeling around tentatively for the slippers that he’ll never get used to, but are so warm once they’re on. Yawning, trying to conjure up some warmth to compensate for what the body is losing. Standing up. Opening the curtains to see the endless white stretch of the world, suddenly so different than the night before: the trees, their leaves, the bushes scattered around the yard, yes, the whole yard and even the sky itself, the horizon, shrouded by death. And it was of death that Nithap thought, of his own. Who could say, who could tell him, tell us, any of us, that death isn’t waking up to a snow-covered world?

This fluttering of his mind, this fog blurring his brain, this cloud covering his consciousness, this sense of doubt, there’s no way that his son—whose name was Nithap Salomon, Sal for the Americans, Tanou for his family—could help him in his struggle against it. Tanou had already left for work, as had his wife, and the little one was at school, like every day of the week, leaving him, the grandfather, alone with this ill-defined, vaporous feeling that he’d never before felt so keenly: it was suffocating. Yet suddenly a burst of energy, a flood of warm blood through his veins, reminded him that there is no age at which one should cease to explore or stop learning. That’s what he always said, what he had said to everyone there in Bangwa the day he left. That lesson, renewed each day, was now taking shape in the flakes he watched gently floating down from the sky, carried by the wind that, in the warmth of his room, he could not feel, but that he knew to be cold, so very cold, a cold that had deadened his body, all the way to the tips of his ears, and cracked his lips, which he now had to cover with cream.

He didn’t brush his teeth or take a shower, but headed downstairs in his pajamas, shuffling his slippered feet, egged on by his curiosity. His eyes brightened only when Marie, the little one, gave him English lessons, shaping her lips into rounds to show him how to pronounce the words.

“Grandpa, snow,” she said in English.

“Why aren’t you at school?”

The little one took the hand of her Old Papa—that was her nickname for him—and dragged him off, without answering his question, or perhaps answering it in her own way. She dragged him outside, under the watchful eye of her mother, who was busily cleaning off her own shoes.

“What about school?”

“Snow!”

What child doesn’t like snow? This child, Marie, six years old, wanted to teach something to her seventy-five-year-old grandfather. She had jumped quickly out of the car, a Jeep Cherokee, angry with her mother, Angela, who was “wasting time”; she’d run into the living room, heading toward the stairs, where she met her Old Papa coming down. He was the one she wanted to teach something: snow. Her enthusiasm was so contagious that her grandfather didn’t even think to put on a coat, especially since Marie, already outside, was disappearing into the flurry of white falling from the sky, joining the universe in its dance. Suddenly remembering her duties—that she needed to introduce him to this new world, her realm—Marie grabbed two fluffy handfuls that she let fall, sprinkling down in front of Nithap’s astounded face. “Snow,” she said, as her own face lit up. She rounded her lips, emphasizing the right pronunciation: snow.

“You’re going to catch cold!”

Her mother’s voice interrupted their dream.

And her mother was right, because her father-in-law was out there, in the middle of winter, wearing only his pajamas and slippers. He didn’t notice that his little one was dressed for the weather. School was closed but they’d heard the news too late, only after they were on their way. Angela came out with an overcoat and boots, since the grandfather was clearly carried away by his granddaughter’s enthusiasm, becoming his granddaughter in some sense, repeating what she wanted him to say, just like in their English lessons, holding out his hands and showing the clump of white: snow.

* * *

The mother shut the door on this literacy lesson in reverse, shutting out the cold and the promise the little girl had made to educate her grandfather by assigning a word to each thing around. With one eye on the screen of her phone, the mother turned on the stove to make hot chocolate, indispensable “after that crazy escapade,” as she heard shouts of joy outside. The little one was thrilled, as was her grandfather: you’d think the two had invented snow. As for the mother, she was getting worried: “Always such cheapskates,” she murmured. She was thinking about the place where she worked, and the university that had sent her husband out on the road so early that morning. She was sure the campus would announce it was closing once he was halfway to his office. “They are going to kill my husband one day!” Through the windowpane she watched the grandfather, who, following the little one’s orders, was both discovering the United States for the first time and coming back to life himself; she shook her head at the sight of them, but used her phone to capture the moment, taking pictures and even a short video—that was what led her to head outside again and join in the dance.

Read full excerpt here.

*************

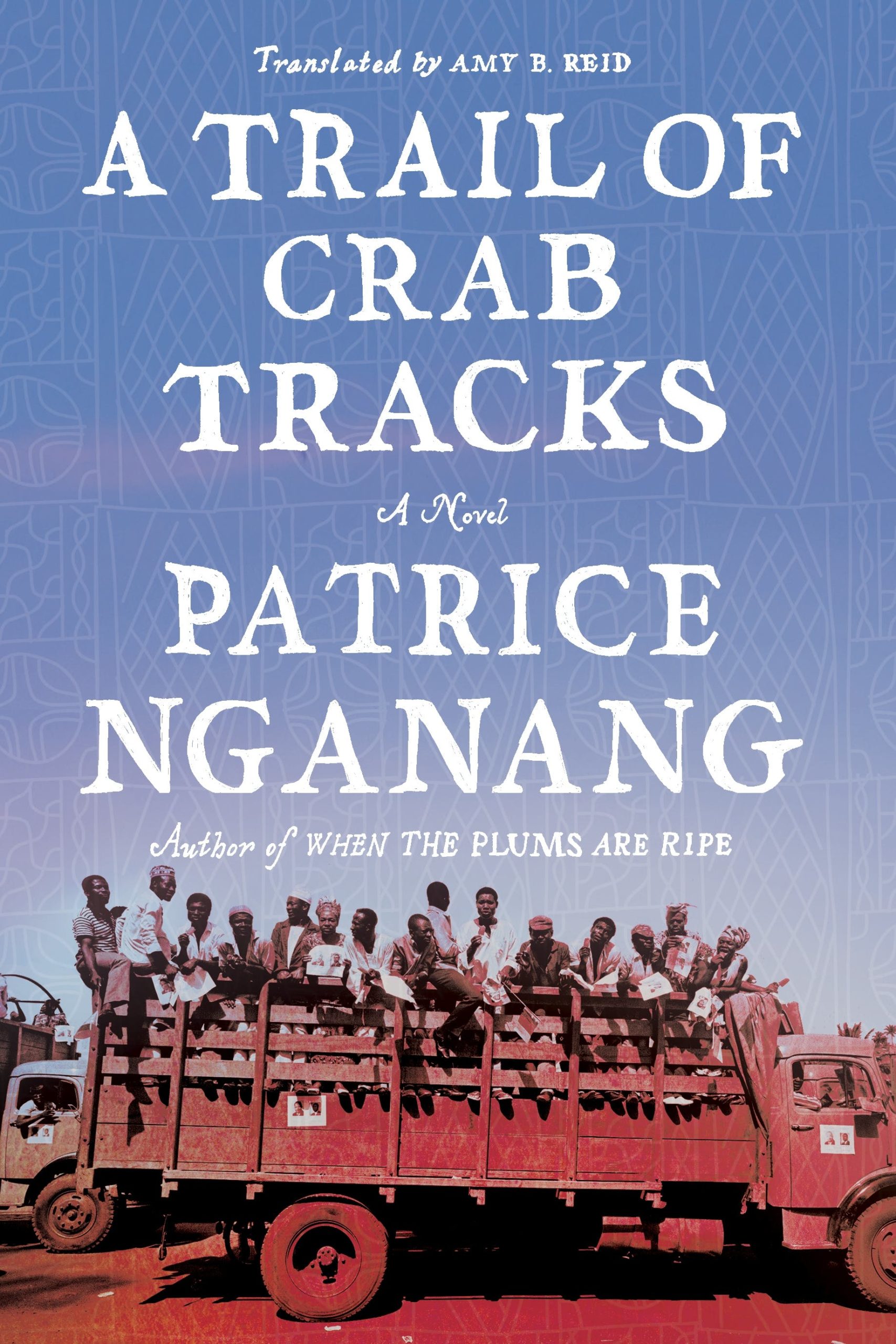

Buy A Trail of Crabs: Amazon | More Options

Copyright © 2018 by Éditions Jean-Claude Lattès. Translation copyright © 2022 by Amy B. Reid

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions