I first read Orhan Pamuk seven years ago at the library section of Muslim Students Society of Nigeria (MSSN) Secretariat at the University of Nigeria Enugu Campus. I downloaded the book the same time that I, having decided to take my writing more seriously, downloaded books by the so-called great literary giants: Oscar Wilde, Leo Tolstoy, Fyodor Doestievsky, to name a few. I remember trying to make it through the body of work of these authors and yet failing to be entranced by the worlds they evoked or the words with which they did the evocation. But when I read Pamuk, I was instantly taken. I remember sitting in that ‘library’, opening my laptop, and reading the following words, “I am nothing but a corpse now, a body at the bottom of a well”. The intriguing opening lines in his monumental novel, My Name Is Red.

From there, it was as though I was set on an exhilarating literary journey. I finished My Name Is Red with a raptorious nature that was unbeknownst to me, revelling in the alluring landscape of the book where everyone and everything speaks. But it wasn’t just the landscape that appealed to me, it was also the lyricism of the language, the depth of the author’s diction, the power to entice and ensnare with words. Here finally was a writer with an enviable skill, the gift that keeps on giving.

After My Name Is Red, I immediately downloaded Pamuk’s other works and devoured them with an insatiable appetite. I remember reading his novel Snow, which has been described as his most political novel. A poet arrives at a city that is going through turmoil after a group of girls committed suicide because the secularists won’t allow them to cover their heads. In this book, the clash and the confluence between East and West, Islam and secularism, comes to light.

I also remember reading his essay collection, Other Colors, revelling in the glimpses of the life of a man whose works I had come to admire greatly. Then there is his beautiful novel, The Museum of Innocence, a heart-wrenching love story that made me cry – the only book that has ever brought tears to my eyes. It tells of a man who falls hopelessly in love and when his beloved dies, he spends the rest of his life collecting and cataloguing every object the beloved ever touched.

Of course, I too remember reading The Black Book in my hostel room at the University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital, losing myself in the labyrinthine world of the novel while keeping at bay the noise emanating from the next room. In the years that follow, The Black Book would be a book that I would return to again and again, to drink from the well of knowledge embedded in it, to drink without ever quenching my thirst. It is one of those books that reveals a secret with every reading. The outline of the story in the book seems, on the surface, to be simple enough: a man discovers that his wife has varnished and goes about looking for her. But then as he wanders through the streets of Istanbul, and wades through the works of a columnist who happens to be the cousin of the missing wife. As he delves deeper and deeper into the varied topics that the columnist wrote about, topics that ranged from politics to religion to mysticism, the search itself becomes more important than that which is sought. Towards the middle of the book, he assumes the character of the columnist, even writing in the columnist’s voice, relinquishing his own identity.

I then found The Red Haired Woman, a book that captures so succinctly the rift between fathers and sons. While sitting in a bus on my way from Nsukka to Enugu, I consumed Istanbul: Memories and the City, the book glistening in my mind with memories of the author’s childhood and the history of a city that has since succumbed to the calls of the West. I then continued revisiting again and again the stories in The Black Book, a book I have read up to ten times. I remember reading The New Life which begins with the words, “I read a book one day and my whole life was changed.” Which seemed a rather apt description of my own experience of Pamuk, reading his words and having my whole life changed by them.

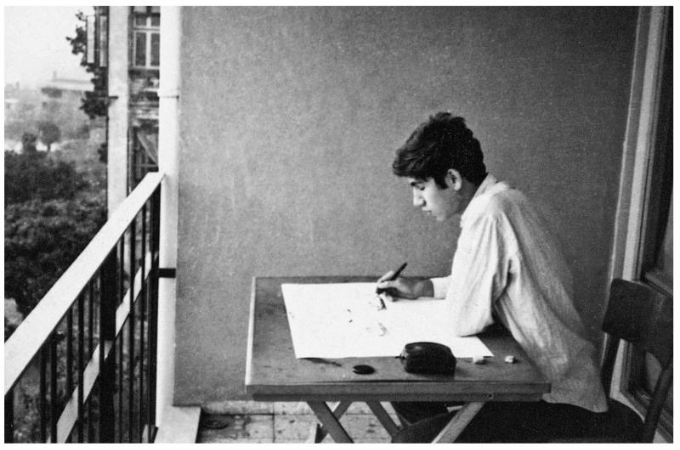

Pamuk once said that his writing brings to mind the image of someone digging a well with a needle. Pamuk was trying to use this image to illustrate both the pace of his writing and the care with which he tells a tale. And with every book, you can tell that a lot of time was expended in making sure the story unfolds beautifully.

As I immersed myself in Pamuk’s oeuvre, there was a certain familiarity that emerged. He is after all writing about a world that is steeped in Islamic beliefs, a world that is well-known to me, having grown up in a Muslim household. But besides this familiarity, this sense of a commonality based on a shared religion, there’s also that illumination of a world that is unfamiliar, the world of Turkey, of Istanbul in particular, the city in which the author has lived for fifty years. I too felt like I have lived in this city. Such is the power of great literature. I have read Pamuk so much and so well that when he speaks of Istiklal Avenue and Beyoglu Streets, when he speaks of the Topkapi Palace and Nisantasi neighborhoods, I feel like he is speaking about places I have been to.

Of course, there are other writers that I love, Ben Okri, Kate Zambreno, Mohsin Hamid, to mention a few, but Pamuk will always be close to my heart, because discovering him meant discovering an enriched world. It meant discovering life. When asked which books I will take to a deserted island, Pamuk’s The Black Book is obviously first on my list. But perhaps it should be his entire body of work, for everything he writes seems to enchant me.

I am currently rereading Other Colors while eagerly awaiting his next book, Nights of Plague, which is due to be released before the end of the year.

Image from TheArtsDesk

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions