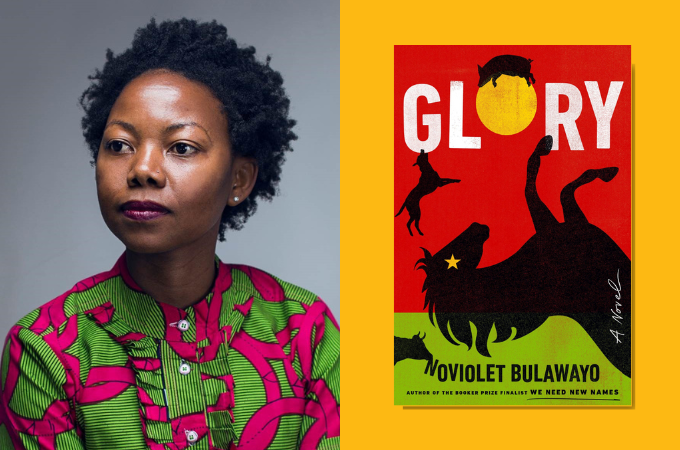

Noviolet Bulawayo’s second novel is an unusual book—an animal story told in hundreds of fragments. I read Glory right around when it was published on the 8th of March and was completely stunned by its boldness. I saw a writer who wanted to forge her own path through literary tradition, drawing from African folklore but also speaking to George Orwell’s The Animal Farm. She was not afraid to take risks, to surprise readers with a new way of encountering fictional worlds, and show critics that African literature will always break with labels and expectations.

Glory tells the story of a country of animals named Jidada. The death of Jidada’s president sets in motion a series of events that rock the nation and put its future in jeopardy. Like other novels in the “beast fable” genre, you can read Glory for its gripping and humorous tale about animals. You can also look out for the ways in which it satirizes Zimbabwe’s contemporary politics and, in some ways modern politics as a whole. Glory was written in the wake of all the disruptions that followed the ousting and eventual death of Robert Mugabe, who ruled the country for 47 years. The novel questions the longevity of tyranny, the seemingly unbreakable cycle of oppression in modern politics, as well as the possibility of revolution.

Bulawayo was born in Tsholotsho Zimbabwe and later moved to the US to attend university. She ended up pursuing an MFA at Cornel University and has since received significance recognition for her writing. In 2011, she won the Caine Prize for African Writing for her short story “Hitting Budapest.” The short story was later incorporated into her debut novel We Need New Names, published in 2013, which got her a Booker Prize Shortlist, won her the Etisalat Prize for Literature and the Hemingway Foundation/PEN Award. Glory was also shortlisted for the Booker Prize, making Bulawayo the first Black African woman to appear on the Booker list twice and one of the few African writers to be listed consecutively.

I went into the interview wanting to talk about the inspiration for the book and her decision to write an animal story. But we ended up talking about lots more: where she was when she heard the news of Mugabe’s ousting, her incorporation of social media in the novel and what social media offers writers at the level of craft, the many influences for the book, especially its unusual structure, and silences around histories of violence, specifically, in this case the Gukurahundi genocide in the 1980s.

It’s been a long while since I had this much fun interviewing someone as I did with Bulawayo. Her humorous side was on full tilt, so there was a ton of laughter and good cheers!

……

Ainehi Edoro

***

Brittle Paper

Hello NoViolet. How are you doing?

NoViolet Bulawayo

I am doing great. Thank you.

Brittle Paper

Congratulations on the new book.

NoViolet Bulawayo

Thank you so very much. I’m glad it’s out in the world.

Brittle Paper

Wonderful. Let’s get right to it. It’s been ten years since your first book. The new book feels special for everybody, including your fans and your readers. How does it feel to get the second book out in the world?

NoViolet Bulawayo

It’s a good feeling. I haven’t been waiting the way some readers may have been waiting though. [laughs]. There are things to do, there’s a life to live. And ten years in creative time is actually not that much.

Brittle Paper

Did you feel any pressure to live up to the success of We Need New Names?

NoViolet Bulawayo

The success that really matters to me is writing the best work that I can, after all, what happens once the book’s been written is for the most part out of one’s hands and therefore not worth the energy of worrying. The pressure then becomes about something else; in my case it was living up to the quality of We Need New Names because I understandably expect to get better with each project to show that a person is growing, evolving. I am very happy that I have the kind of team that allowed me the space and pace to achieve this goal; it’s very important to bring out a project at the right time because there are instances where you can rush a thing before the thing is ready.

Brittle Paper

What do you think is special about now? What’s right about this moment?

NoViolet Bulawayo

It’s a moment that gives me the precious gift of relevance; Glory is in many ways still a happening story, and not just in the specific physical space that inspired it; it feels like there are enough Jidadas out there with many people over the world fighting tyranny in all forms, including in my other home, the US. Glory, which is dedicated to “all Jidadas everywhere,” comes at a time when it can be part of needed conversations.

Brittle Paper

The central historical background in the novel is Robert Mugabe’s fall in 2017. Where were you when that happened, when you heard that he had been ousted?

NoViolet Bulawayo

I was in Oakland, California when I heard the news I never thought I would ever hear because, I mean, if you grew up in Zimbabwe under Mugabe, who defied the people’s will to replace him through the electoral process by a combination of rigging, intimidation, and electoral violence, who once said, “Only God who appointed me will remove me, not the MDC, not the British,” you kind of resigned yourself to the fact that he wasn’t going anywhere.

Brittle Paper

I’m struck by your suggestion that there’s something so unimaginable about his fall, something strange and dramatic. What is so absurd about how this notorious leader came to an end?

NoViolet Bulawayo

It was the unceremoniousness of it. How a figure who’d perched on the tower of invincibility for the longest time was suddenly rendered fragile, vulnerable, powerless.

Brittle Paper

Did you know immediately that you were going to write about it and that it was meant to be a novel?

NoViolet Bulawayo

I knew I was going to write about it right away, but as a non-fiction project. I wrote a proposal within a week of his downfall and very immediately started my trips in and out of Zimbabwe – the first one just to be on the ground, to see for myself so to speak (the hope and optimism still haunts me). I’d move there a few months later, to research and write. But of course, at that time, so much had been, and was being written about Robert Mugabe it felt like there really was not much left to say. Besides, the drama on the ground very quickly became outrageous and bizarre, it felt like it was outcompeting my writing, and that I needed a technology to allow me to match the absurdity. Fiction, and specifically using animals for characters allowed me to do just that.

Brittle Paper

I find it fascinating that you refer to your method as a technology. Can you say more about that?

NoViolet Bulawayo

Technology as in medium, a way of presenting the story. The benefits were immediately obvious – the freedom from facts meant I had the license to make stuff up to cover the true bones of the story, I could go all out with my imagination, anthropomorphism, use of satire, along with other limitless devices of fiction.

Brittle Paper

Launching into the major aesthetic choice that you make—of using animals in this text—you’ve already said that it gave you lots of freedom, but could you maybe elaborate a little bit more on what animals do for you that human characters may not have been able to do?

NoViolet Bulawayo

Freedom as in animals, and by extension, folklore, allowed me the distance to negotiate real, recognizable figures and familiar storylines. Because anything can happen in a folkoric kind of framing, I had the liberty to distort and defamiliarize – from character exaggeration for specific effects, to hyper levels of absurdity, to magical elements like the victims of the Gukurahundi making an appearance in the form of red butterflies, to the Old Horse returning to his Jidada after his death, to the Savior having a thing for his virtual assistant, Siri, to spirits coming through from the land of the dead. Most of these things would simply not hold or convince in a Jidada of human beings. Here, they exist without the burden of having to make sense or being justifiable, they just need to belong in the universe they’ve been created in.

Brittle Paper

So, what went into attributing various characters to various animals?

NoViolet Bulawayo

I did consider, but very loosely, the general animal characteristics of some of the characters, for example, the crocodile is cunning, vicious, violent, the powerful animals in a farm setting tend to be the larger ones, how the goat works as a wanderer, the pig unclean and greedy. But at the same time a good part of the characters are quite randomly cast, given individualizing narratives and characteristics, and having them serve as the story needs them versus act according to their animal natures. This is how characters like Comrade Nevermiss Nzinga is able to surprise us – we don’t necessarily expect her backstory and story when we first meet her. Human characteristics notably override the animal, the effect being to amplify the absurd and surreal which was at the center of making this novel work. It was a whole production to manage, but I am grateful to the animal stories I grew up with – their flexibility gave me the license and the permission for these kinds of decisions.

Brittle Paper

You say it was a production. Is it a process that you enjoyed or was it very torturous?

NoViolet Bulawayo

Glory was a very challenging and humbling book to write, both on the material and structural levels, I think I’m still in reverence of what it took to bring it to life. That said there was also so much joy for me in creating this project, joy being a necessary part of my process that, among other things, renders my work tolerable to me, and hopefully approachable to the reader.

Brittle Paper

I have two more questions for you about animals and then we can move on to something else. Where did the idea to feature animal character come from? Because it’s a very specific aesthetic decision. What sparked that move?

NoViolet Bulawayo

There was a time – around 2019, that I started noticing Zimbabweans on social media referring to the country as an animal farm, sometimes using animal avatars, as well as characters from George Orwell’s novel to talk about our political leaders or the increasingly frustrating state of the nation. This creativity, at a time in which I was struggling with how best to package and tell my story, not only made me pay attention, but it immediately took me back to a childhood steeped in animal tales told to me by my paternal grandmother. I committed to experimenting with the form, and it worked.

Brittle Paper

You refer several times to orature, and I know that you’ve also said elsewhere that George Orwell’s Animal Farm is an influence. But I am also thinking of early African novels—turn of the century Xhosa, Zulu, and Shona novels—there are quite a bit of animal-centered stories. What was it like reaching into existing African literary practice of storytelling through animals?

NoViolet Bulawayo

Growing up I did read a lot of Ndebele literature from writers like Barbara Makhalisa, Ndabezinhle Sigogo, T. M. Ndlovu, J. Sibanda (the first two were especially prolific) and it’s striking me now that I don’t always talk as much as I should about what was a significant influence, and to which I’m obviously indebted. This is also the literature that allowed me to see myself, my experience, and my language on the page first, which among other things allowed me to approach writing with a sense of groundedness. To come back to your question, I don’t necessarily remember this literature for storytelling through animals per se, though there were a couple of exciting exceptions (I’m speaking here strictly of Ndebele literature). It’s possible that having been brought up steeped in the folklore of their elders and in the very language they were writing in, this first generation of young Zimbabwean writers writing in Ndebele was anxious to make a break from their literary origins, to make sense of the different world around them (for most educated young people, this now included the city, whose modernity offered new stories from those they’d grown up around). When the exceptions do tell animal stories, as T. N. Mkandla’s Abaseguswini le Zothamlilo, which roughly translates to “Those in the bush and those who sit by fires,” the written stories, like their oral influences, are dramatic, wildly imaginative, full of humor, and boldly anthropomorphic, the veil between the species is super thin, as the title suggests. How Glory executes the animal comes from this background.

Brittle Paper

Speaking of social media, I first saw Twitter incorporated into an African novel with A. Igoni Barrett’s Blackass a while back, and I find it fascinating to have both worlds, the novel and this new discursive form mixed together. What does social media do in terms of craft for a novelist? What does incorporating social media help you do at the level of form and structure?

NoViolet Bulawayo

For me the draw for using social media was innovation, the opportunity to disrupt the traditional form with something outside of it, and potentially more interesting. We are storytelling beings, and this moment finds us doing so through different mediums specific to this time– I wanted my work, itself inspired by social media as a space, to give some sense of that. I especially appreciated how effective Twitter sections were in helping me condense material and capture, very quickly, collective moods and voices, which was important in a novel that sometimes zooms in to grand moments. For a broad novel that is telling the story of a nation, of a vast cast of characters, of many moments, this form offered something I could use.

Brittle Paper

Speaking of formal experimentation, the structure of the book itself is unusual in the sense that it is a collection of fragments with sub-headings. Can you tell us a little bit about the form?

NoViolet Bulawayo

I saw and heard Dr. Ghirmai Negash, a professor of English and Postcolonial studies, present his work-in-progress at the Stellenbosch Institute of Advanced Studies, where we were both fellows. It was a translation of the first Ethiopian language novel to English, and I remember he’d projected some pages in Amharic. The eye immediately picked up on these bolded subtitles that marked the section titles, and when the English translations went up I liked how the sections were working to frame the story. I left that presentation actively thinking about adopting the structure and that my then long chapters could use the breaks and framing (I’d of course seen and loved it in works like The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, Texaco, and Palmwine Drinkard). I would go on and start to incorporate the sections based on moments, which helped me focus the novel – at one point I remember I was working with a draft that was around 700 pages – and they became a system of managing what was important, and losing what we could do without. But the structure went on to serve in other ways – it was better suited to the multiple, even extra, stories and threads running throughout the novel and at the same time made it easier to incorporate the social media forms as well. It’ll be up to the reader to speak to this, but I think that given the length of the novel the sections may break the monotony of the reading process.

Brittle Paper

A brilliant answer. Let’s talk about humor. Glory is a very funny book, NoViolet. I don’t really know you that much, but I never thought of you as a “funny” person, you know? But then, I read this book and I’m like, “Lord, it’s ridiculously funny.”

NoViolet Bulawayo

Most people don’t think I’m funny because they only ever experience me in English, and of course I don’t belong to English in a way that always allows the humorous part of me to come out. But my writing draws from my Ndebele, of which humor is a big part of the language, and by extension my voice, so that it will inevitably become a part of most of my work. It is also an old craft element that’s especially attractive for writing resistance, for writing against power because to render power laughable is to challenge and undress it though most of the leadership in the story that inspires Jidada are doing just fine to invite ridicule without any help. There is also the fact that most of my work is a bit heavy, humor is what allows me to make it go down easier as well as even approach the writing myself.

Brittle Paper

Yeah, that’s beautiful. Thinking of heavy subjects, you spend quite a bit of time on the Gukurahundi killings in the 1980s. For a book that is so much about the present and the future of liberation, there are these powerful moments when you really address the history of violence. Why was it important to you to address that particular moment in the past?

NoViolet Bulawayo

Because the past is very much present, here reminding us that the said liberation wasn’t about and isn’t for everyone, for some it was very violent and continues to be. This is no longer the case now, but for the longest time, part of what always struck me about this particular story, which is at once personal and communal, was its “unspeakability,” whether it was the government’s silence in acknowledging this bloody episode in Zimbabwe’s history and its role in it, the silence or the cryptic talk of our elders and older siblings who’d lived through it when we were growing up, one’s own silence (if like me, they were old enough during some of its episodes to “see” what was happening but didn’t necessarily understand it), the silence from the general failure of language to serve the victims. We see Simiso embody this later silence in Glory, but then she breaks it, not just for herself, but her daughter, neighbors, and in the end, the whole nation. That Zimbabwe has actually made news for the continued vandalism of Gukurahundi memorials, besides being insulting, hurtful and devastating to the victims, sends the sinister message for the victims to in fact continue living in silence (the Gukurahundi memorial in Glory was a response to this frustrating state of affairs by the way). Fortunately, people have found their voices and do not need permission to speak their truths – one can now find numerous interviews, recordings, testimonies on the internet and in print, while Zimbabwean writers like Novuyo Rosa Tshuma, Christopher Mlalazi, Siphiwe Gloria Ndlovu and Peter Godwin have written around this moment.

Brittle Paper

That’s true. I have two more questions for you. One of them is the place of women in the story. The women are probably my favorite lot in the story. I particularly like that first moment we see them together, the chapter titled ‘The Returnee.” We hear these group of women channel the zeitgeist, their conservation captures everything that is meaningful about the moment and the past. What are you saying about those kinds of feminine spaces and knowledge-making?

NoViolet Bulawayo

That they are important sites of community and awareness – the gathering happens quite spontaneously to welcome a prodigal, and at the moment “motherless” daughter back home, giving Destiny much needed family. At the same time it’s a potent political space wherein the state of the nation is interrogated by characters who include an ex-combatant who fought in the war but is not recognized for it, a spirit medium who among other things bridges the worlds of the living and the dead, and those who are leading the only feasible and confrontational resistance in Jidada at the time (the Sisters of the Disappeared). Our communities are filled with such formidable women even as our patriarchal histories and presents tend to flatten their roles and do not always give them due space. In Glory they collectively frame, inspire, nourish, and channel Jidada’s true revolution despite their circumstances. In addition to all this, it’s a “femal,” Comrade Nevermiss Nzinga, who ends up being the one to take one of the most decisive actions at the end of the novel. I guess what I’m saying is that if we dare to give women the room to be active participants, if we’re not busy oppressing them, they may just free us all.

Brittle Paper

That was beautiful. That scene was like out of a Hollywood movie. That was very satisfying.

NoViolet Bulawayo

Writing it was equally satisfying. It’s a tribute to female freedom fighters who fought and made many contributions to the liberation struggle, but we don’t quite hear enough of their stories. Just as we don’t hear enough of spirit mediums like the Duchess of Lozikeyi, who reminds us that we have indigenous spiritualities that allow us to reconcile the past of our histories with our presents and at the same time give space to the community to collectively process various traumas and provide the possibility of healing. It really felt urgent and important to center these narratives.

Brittle Paper

Final Question: what is revolutionary storytelling to you?

NoViolet Bulawayo

It’s the kind of storytelling that defies power, that imagines against all forms of tyranny and dreams new, better, possibles. It ignites imaginations. It unsilences. It’s free and it frees. It’s against ugly and scoffs at evil. It gives hope. It saves. It shifts the center. It unsettles. It invents new languages. This and more.

Brittle Paper

Thank you so much, NoViolet, for taking the time, to talk with us today.

***

Buy Glory here: Amazon

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions