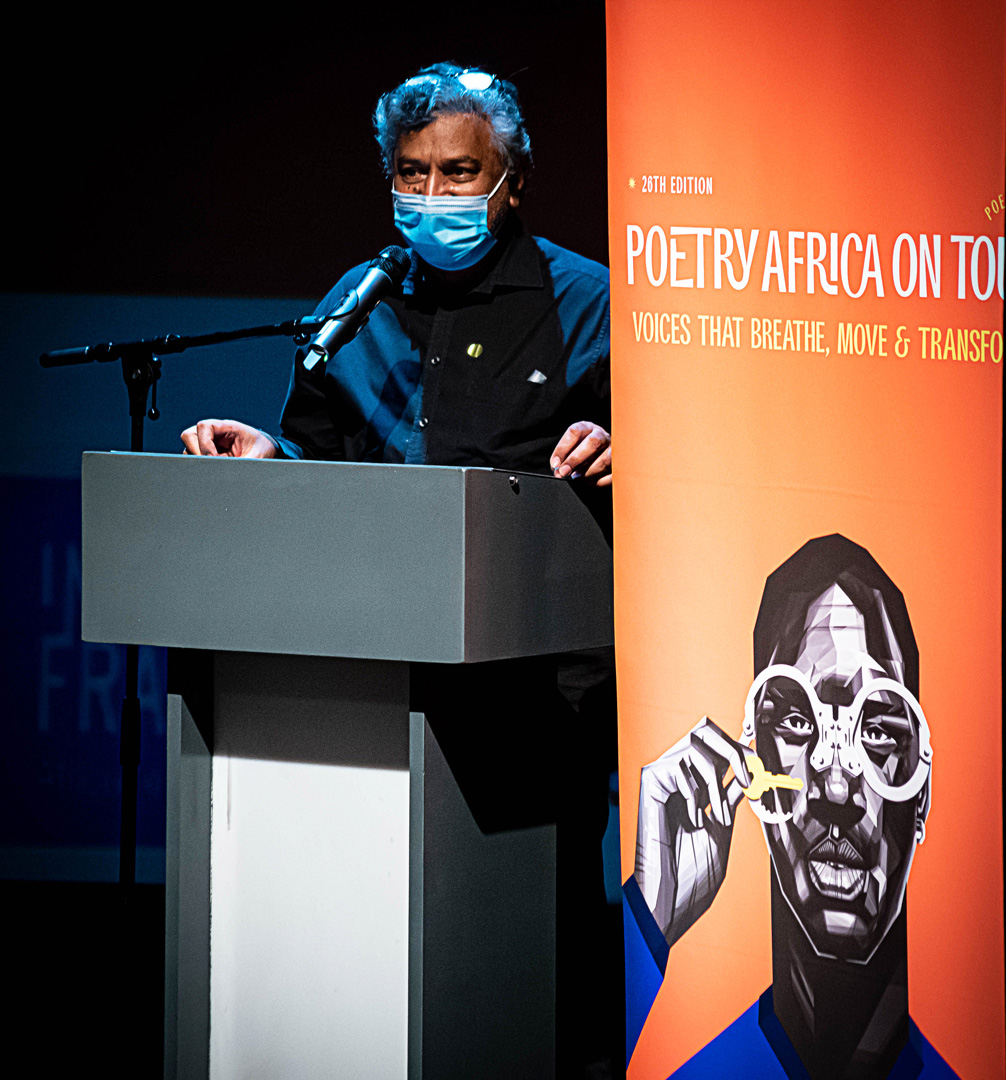

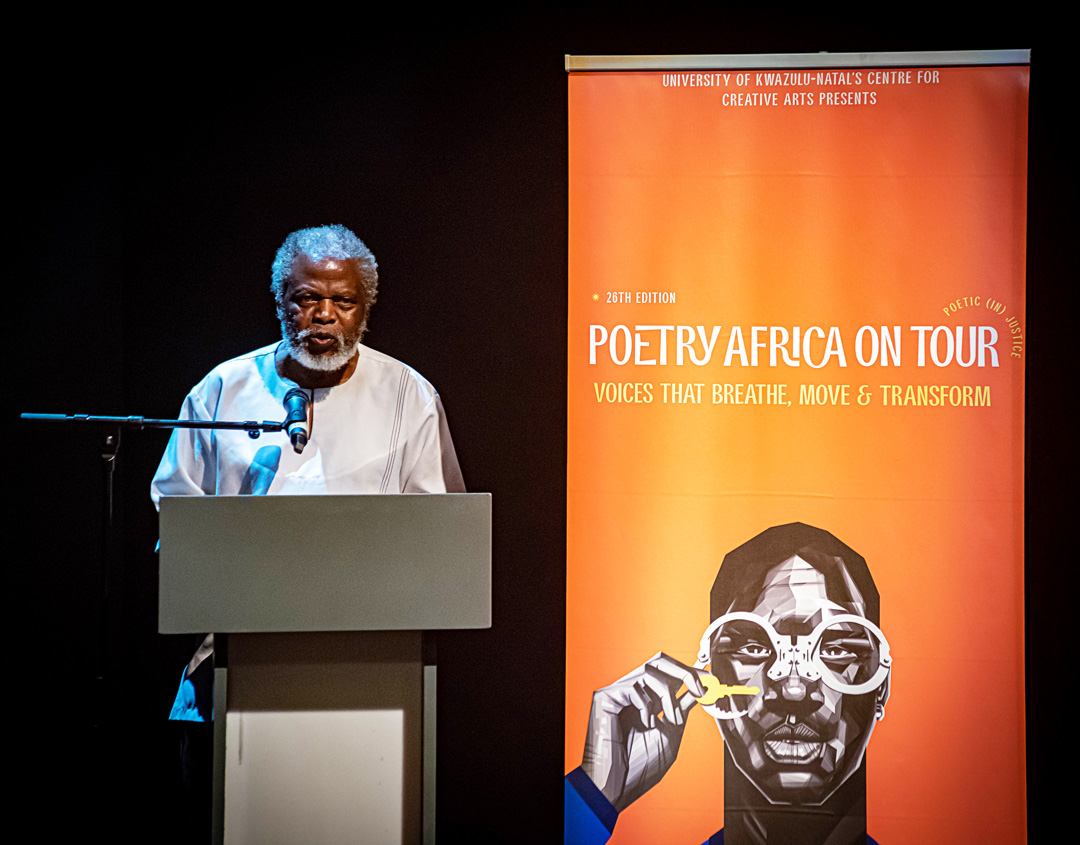

The 26th iteration of the Poetry Africa festival ran from October 6 – 16. For the first time events were spread across two cities, with the Johannesburg leg starting proceedings before moving on to Durban on October 10.

This year’s theme, as presented by the Centre for Creative Arts at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, was Poetic (In)Justice: Voices that Breathe, Move and Transform. Featured poets in the categories of Legendary and New Generations were Diana Ferrus and Xabiso Vili respectively.

Diana Ferrus delivered the keynote address online on Monday, October 10 at 3pm, thus inaugurating the programme’s third location: the Internet. A dense roster, including the Mafika Gwala lecture, was available electronically for those who could not move between the two cities, but would still like to participate in the festivities.

See select coverage of the Johannesburg leg below:

What’s a Woman’s Worth? – October 6

The provocation for the opening night of Poetry Africa invited us and a cross-generational selection of black and brown poets to deliberate on the attributes that constitute a woman’s worth. How has the enshrinement of human and women’s rights in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights as well as the Bill of Rights, affected how we think and talk about the challenges women face in defining their value? In a country awash in gender-based violence and occupational inequality, this focus on women by women performers is not only necessary, but constructive in its exploration of the degradation and celebration that determine a woman’s worth.

The lineup of featured poets at the Keorapetse Kgositsile Theatre was headlined by Lebo Mashile, Phillippa Yaa De Villiers, vangile gantsho, Nomashenge, Belita Andre, and Roche Kester.

With a start time of 7 PM at the poshly decked UJ Arts Centre, wrangling six slam poetry sets, housekeeping announcements, and introductory speeches in 90 minutes proved to be impossible for host Siphindile Hlongwa.

By the time Roche Kester appeared on stage, 45 minutes had elapsed but Johannesburg’s enthusiasm was not dulled. The audience was simply happy to be included in this year’s proceedings. “Roche!” shouted a familiar voice from somewhere behind me, but the poet shut him up with an aggressive, “Shhh! Listen to the poet.”

Before her introductory speech emphasized her Indian appearance, brown culture, and black political identity, Kester set the ground rules with a poem that outlined the responsibility of the listener to the poet and vice versa. Those who have carried hurt into the auditorium are invited to heal alongside the speaker, as she poetically unpacked her intersectional baggage.

“I have a lot of problems,” she admitted, as a queer woman of color with depression, who is also a survivor. Writing the trauma is a coping mechanism reflected in selections that addressed sexual assault and mental health. “I am not a sad person, though,” she reassured the audience before a final poem celebrating the sexual discernment exercised by her vulva, which was the cue for a visibly pregnant Belita Andre to enter the stage full of meaning and life.

“Just to give you a quick view,” the Pomfret-born poet whispered in profile, the better for us to see her baby bump. The knowledge that there are two beings onstage imbued Andre’s set with gravitas. Her tonality and movement trusted in this quiet power, eschewing the demonstrativeness usually associated with performance poetry. The subject matter tended to melancholy with refrains that demarcate poems that would otherwise segue into each other. Sometimes she helped the listener with a humble, “Thank you,” but mostly quietly ploughed on. A cultured singing voice was held in restraint so as not to overpower her import with affect, in a literary set that lended itself to the stage as well as the page.

Phillippa Yaa De Villiers rounded out the pre-intermission entertainment with a set as eccentric as Andre’s was pensive. Her material ranged from a struggle to fit into a pair of jeans and day-drinking during lockdown, to a tribute to Keorapetse Kgositsile and a portrayal of Christ as a woman. De Villiers ramped up the performativity with stamps, screeches and swoons, then brought the crowd down into her bosom with intimate sidebars between readings. The stagecraft was masterful as the audience was kept at the very edge of equilibrium.

It is 9:05 PM by the time Hlongwa permitted the attendees a 10-minute break. With catering to be consumed and mingling to be done after the show, events wrapped up well after 11 PM. I lamented the 45-minutes of speeches with which we started, and followed those up the stairs who did not want to test the availability of Ubers just before midnight on a Thursday.

Tilting the Scales – October 8

The theme of this night was disruption at the levels of form and content. The lineup was described as non-conformist in performance, poetry making, as well as social convention. It fell upon Thando Fuze, Sabelo Soko, Lydol, Modise Sekgothe, Xabiso Vili, Mana Bugallo, and Siphokazi Jonas to translate their creative practice into transformative activism. The first poet on stage, Thando Fuze, responded positively to this provocation at UJ’s homely Bunting Theatre.

The Durban-based poet’s work centered on family, love, childhood, and politics, which are just some of the things we have in common as human beings. She began with a recollection of the lessons learned in first grade, all of which prepare the six-year-olds in class for the world of gender-based violence they are to inherit. Nursery rhymes broke up harrowing tales of violence perpetrated against women for reasons ranging from sexuality to excellence in “typically male” pursuits. “By the time I was nine I could tap a football 200 times,” asserted Fuze: a fact which made the boys on her street afraid of her. The poet explored this fear over the length of a single poem spanning the length of her set, showing how it feeds male entitlement and the patriarchal prescriptions that underpin atrocities such as corrective rape.

At the center of our failure to protect our community members is the complicity demonstrated by neighbours who allow domestic violence to go unchecked until it is too late. Sabelo Soko – second on stage – concerned himself with nothing if not the state of our communities. His subscription to the philosophy of “spinning” lays bare his loyalties, as he explained that it comes from car thieves who did their dirt out of town in order to plough the plunder into their impoverished neighbourhoods. His largely vernacular set spoke to the erosion of communal values brought on by the encroachment of social media culture. Neighbours used to ask each other to watch the kids and take in the washing should it rain while on an errand to make a phone call, he lamented. Now our communities are characterised by the fear and competition that go hand in hand with capitalist consumerism.

From the multilingual melting pot that is Cameroon hails a poet whose rootedness in humble beginnings was symbolised by the bare feet with which she traversed the stage. The path to slam poetry stardom, a doctoral degree in economics, and social activism began with homelessness, begging on the streets alongside her mother. Trauma collected in a school massacre in which eight of fifteen pupils survived made it into the swathe of West African material she brought to the Joburg stage. Snippets on love and womanhood were woven in, in a set made for audiences unfamiliar with her work.

As usual, we broke for intermission 40 minutes after the advertised ending time. Again there were speeches that ran overtime after a late start. Perhaps it is the ingrained art-scene culture to ease into events with fashionable nonchalance, but as a courtesy to reviewers with multiple commitments, the organizers of Poetry Africa would do well to keep to the schedule in the Durban leg of events.

***

Poetry Africa ran from October 6 – 16. An overview of the Durban events will be posted soon.

Image credits to Kitso Sedumedi and Lindo Mbhele.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions