Prologue

High Court, Harare, May 2008

Robbed of light, she was unable to discern the transition from day into night, or one day to the next. The hours blended into each other seamlessly. There was no beginning or end. No sense of the passage of time. In solitary confinement she was in complete isolation, with no access to the other prisoners. By virtue of her crimes, which were classed as serious offences, she was assigned to a private cell – an advantage if one considered the overcrowding in prison cells, but it also meant she was isolated, her own thoughts tormenting her. She knew he had deliberately engineered it so that she would go insane. She could no longer vouch for her own sanity because she had now reached a stage of talking to herself. Conversing with people she had conjured up, some from her past, a few from the present. When she could no longer invoke them, she spoke to the cockroaches or spiders that crawled into her cell. At first she had been fearful of a furry spider with long legs that had crept furtively across her face and had screamed before flicking it away and squashing it to death. An action she later regretted as she reflected that it probably meant her no harm. So when another spider made its way into her cell, she had been more welcoming. Even letting it rest on the palm of her hand. The legs tickling her, reminding her of her sensibilities and that she was not completely dead. Now she knew better; those arachnids were harmless. It was people she needed to be wary of – and they were outside, living their lives with careless abandon while she merely existed inside this purgatory.

She heard the footfall of steps. The police were her only conduit to the outside world but even then they only responded to bribes. They brought her food on occasion, lumpy porridge or sadza with a few strands of watery cabbage, but she never partook in any of the meals. She did not drink the water either. Her paranoia would not allow her to. She was fully reliant on her lawyer to bring her dry goods and mineral water on their consultations. Not that she was ever hungry. Oftentimes her lawyer would try to coax her to eat, insisting that she would need her strength to stand trial.

The jangling keys turning in the door made her jump, snapping her back to the dreadful reality of her prison sojourn.

‘Missus Ngozi. You have your court appearance today.’

She felt apprehensive about leaving the prison cell, uninhabitable as it was. She was no longer as conscious of the foul odours saturating the air as she had been when she first arrived. The filth had caused her to retch until she was hollow inside. Now she had become acclimatised to it and the smells permeated the pores of her skin. She was as filthy as the uncleaned toilet in her cell. Yet still she found refuge in these unsanitary surroundings. The walls shielded her from the judgement and scathing condemnation. There was no sympathy in the world, only wrath.

She emerged on the outside, welcomed by the blinding light of the day. Instinctively, she shielded her eyes with her hands. She hated that the radiant sun was shining a spotlight on her. The prisoners were piled unceremoniously into the prison van with other inmates. The wire mesh over the windows allowed some shafts of light that illuminated their faces. It also gave prisoners a glimpse of the freedom they yearned for. She was inconspicuous now – you could not set her apart from the rest. As they were transported from the Harare Remand Prison to the city centre; the other inmates chatted among themselves. She remained buried in her own thoughts, jostled in discomfort as the van sped over gaping potholes in the roads.

She was assisted out of the van in leg irons. As a Class-D prisoner they said she was a flight risk. The nerve. The minute she emerged from the van there was a barrage of cameras on her. Foreign media correspondents from Al Jazeera, the BBC and the SABC. They clicked furiously, trying to capture her humiliation and showcase it all over the world.

‘We are outside the High Court today where the General’s wife appears to be facing charges. Mrs Ngozi is set to take the stand in the most anticipated trial of the year!’ spoke another journalist from the state media.

She avoided the cameras, looking ahead as she shuffled towards the court. In the days when she wore long Brazilian hair and Gucci sunglasses she had been able to hide behind them but there was no more hiding; she was exposed to the world. She felt very vulnerable and afraid. Once upon a time she had been fearless. She recalled an incident during the campaign trail when she had lost her cool after being harassed by some journalist. She had slapped him across the head with her Louis Vuitton clutch bag. Her security personnel had to intervene, but the incident had caused a skirmish. In those days she had power, or at least a proximity to it. Today she was powerless, like Samson, her hair shorn like a frightened sheep. Looking away gave no respite from the steely glares so she looked down instead, at her feet. Walking was a struggle and it wasn’t the leg irons that made it difficult; it was the beatings she had received. In the middle of the night, she was often woken up to face the assault of police. She knew they had been sent by him. They inflicted the scars where they were not visible. Under her feet, on her back.

‘Confess!’ they said. ‘Confess.’

She had no idea what she was supposed to be confessing to. Even the priest who had been assigned to her urged her to confess her sins.

‘Kill me,’ she replied, ‘just fucking kill me!’

With no confession forthcoming, they beat her till she blacked out. She was comfortable in that space, veering between sanity and insanity.

The reporters accosted her, bombarding her with questions. She responded to none. That had always been her default response. Aloofness. It had not endeared her to the masses then and it further alienated her from them now. She did not want to meet their eyes, those contemptible stares. The disparaging remarks about what she had become. She could hear the gasps of horror her appearance elicited. When her husband was on the campaign trail, it wasn’t his speeches that had excited reporters; it was her sense of style that had been fodder for the tabloids. She had always looked fashionably elegant in Chanel and Dior. Now she looked jaded in her green prison frock that hung on her like a hospital gown. On her feet she wore black plastic flip-flops. The ones you found at Bata. Pata Pata they called them. She knew of them because her domestic workers wore them. She had always worn Havaianas, her brand of choice even as a young girl. Her lawyer had offered to buy her a pair. She had declined, of course; it’s not like she needed to turn up in prison or for her court appearances in branded flip-flops. She was long past the point of caring about those material comforts that were once the hallmark of her former life. She had fully embraced prison life and its rigours.

As she advanced towards the courtroom, she wondered if this was how Jesus must have felt as he carried his cross with the crowds jeering and heckling in the background. Except, of course, he was pious and sinless and she couldn’t claim to be either. Church had rarely even featured in her life. They had celebrated Easter and Christmas ceremoniously, but beyond that there had not been room for religion. Now she thought about God often. The Afterlife. It had all started with that priest who paid her weekly visits. Father Dominic. He said he had come to save her from hell. She had laughed at him. What did he mean she could avoid hell? She was in hell. Every single day of her life was hell. That dirty, damp cell was a hellhole, robbed of sleep between 800-thread-count white cotton Egyptian sheets. Torture was being denied the luxuries and comforts she had been accustomed to. She used to have croissants and salmon for breakfast, not lumpy porridge laced with rat poison. Hell was the torturous beatings she endured, causing her body to swell in pain. The voices in her head tormented her. While hell might have been an abstract place for him, she was living it. Every single fucking day.

The law required that any arrested individual had to be charged within 48 hours and be brought before a court. She had been in custody for 30 days. And the law had not been applied consistently in her case because he was above the law. He could change the rules to accommodate himself.

Her lawyer, Beather Mteto, was at the courthouse to meet her. Dressed in a crisp linen suit, high heels and her braids styled neatly, she enveloped her in the scent of For Her by Giorgio Armani. The musky notes of bergamot and mandarin lingered in the air and it had been one of her favourite scents pre-incarceration. Her lawyer immediately took over, fielding questions from the media. She was adept at shielding her from the brutal onslaught. She tried to remain expressionless in the face of more clicking cameras.

‘My client has no comments!’ said Beather with authority, her voice rising above the chorus of those competing to get a word in.

Beather was a human rights lawyer with a solid reputation and a thriving practice. She had been the only lawyer willing to represent her. Others in the legal fraternity thought it was career suicide. Beather had argued that some cases were not about winning but about justice, as elusive as it was. Some accused her of doing it for the money, to which she argued she was not receiving a cent from Mrs Ngozi, whose assets had all been frozen.

The courtroom was just as noisy. Filled to capacity as though it were a movie premiere and she was the leading actress being led to the dock to face the charges levelled against her. This was Zollywood and she was there to put on an award-winning performance. Her freedom was at stake. She was thankful that no cameras were permitted in the courtroom. Out of the corner of her eye she saw someone furiously sketching her face. There was always someone trying to capture a moment, to sketch her guilt.

I am not a criminal. The real criminals are out there. I am just a scapegoat. The fall girl.

It was only when the presiding judge walked in that the courtroom settled slightly. Judge Rita Rezende was presiding.

She chuckled for the first time, thinking about how they had sent a woman to lynch her. Rita had been a friend once upon a time; they had lunched together on several occasions. Yet today Rita was in her red robe, her head crowned with a white horsehair wig, a vestige of the colonial past that the country still hung onto. She could see Rita sweltering beneath her wig. She wondered whether it was the air-con that wasn’t working or if it was just her nerves. The state prosecutor, a thin wiry man in striped black Crimplene, presented his evidence against her. She felt the sweat trickle down from her armpits and between her thighs. She wrung her hands nervously. She no longer sported manicured hands with acrylic nails. She had bitten her own fingernails out of sheer fear and anxiety.

The judge read out the rap sheet of charges. They were like the credits at the end of a movie.

Attempted murder

Assault with the intent to cause grievous bodily harm

Evasion of justice

Fraud

Malicious damage to property

Money laundering and bribery

‘How does the accused plead?’

There was a long pause as all eyes settled on her. She opened her mouth but no words emerged. She coughed, clearing her throat.

‘How do you plead?’ said the judge, repeating the question in a higher octave, as if she hadn’t heard it the first time.

‘Guilty!’ she heard herself spit out.

The courtroom was in uproar. Beather was horrified. This was not the script she had rehearsed with her client in their last four meetings before the hearing.

‘Silence!’ said the judge, slamming down her gavel.

‘Objection, My Lady!’ said Beather. ‘I would like to confer with my client.’

‘Overruled. The accused pleads guilty. The court will sit on 23 September 2008 for mitigation hearings and sentencing. The accused is to remain in state custody until then.’

The prison guards came for her, escorting her to the awaiting van. She could see her lawyer smarting with anger. Beather was trying hard to maintain a neutral facade for the benefit of the journalists who pounced on her like vultures.

She did not care any more. She was ready to die. By the time September rolled around she would be no more. She wanted to be reconciled with her parents. The first question she would ask them was: Why did you bring me into this world only to abandon me?

***

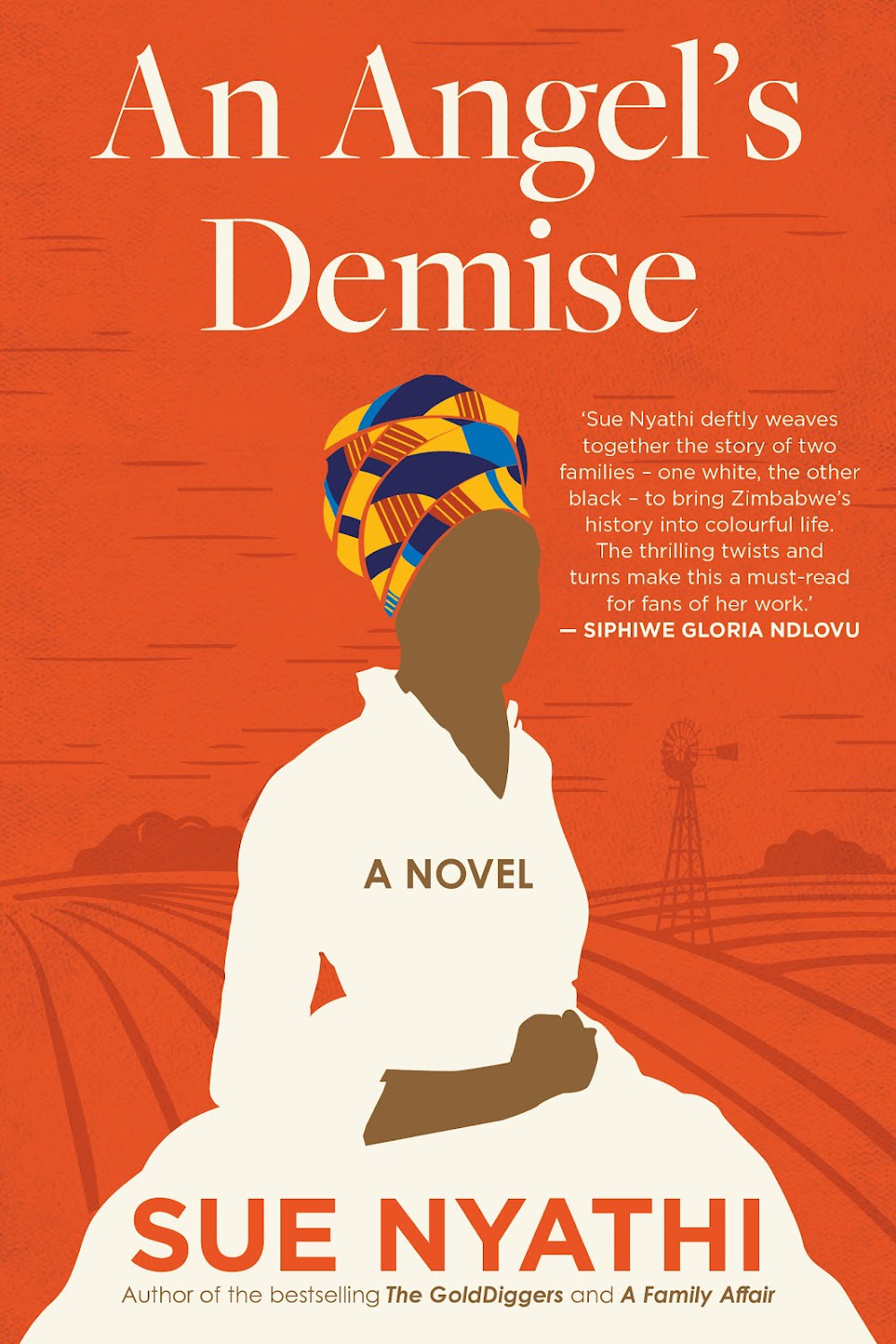

Buy An Angel’s Demise and read the full excerpt here: Amazon

Excerpt from AN ANGEL’S DEMISE published by Pan Macmillan South Africa. Copyright © 2022 by Sue Nyathi.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions