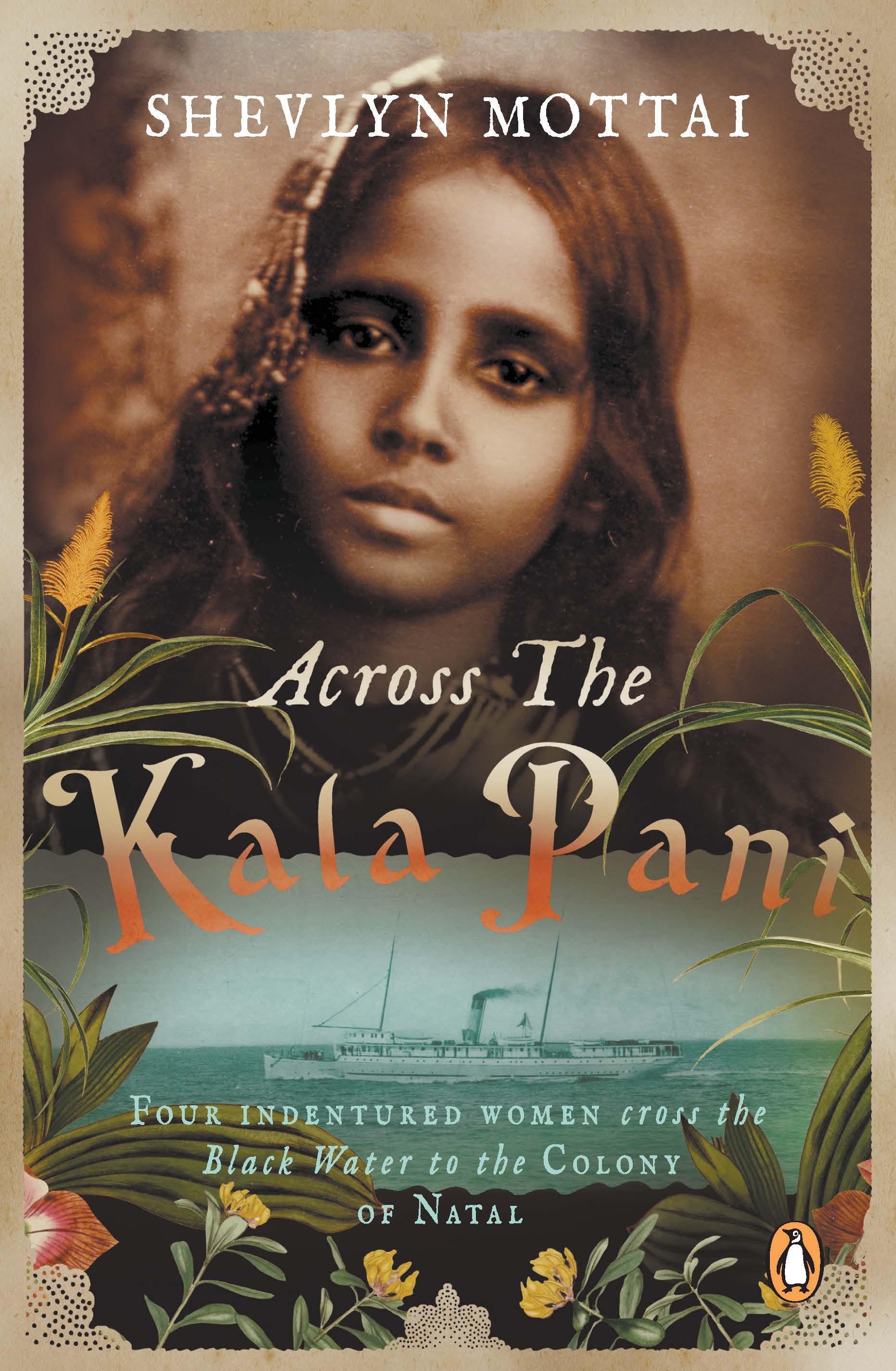

1

Coolie camp, Madras

April 1909

Sappani stared vacantly at the snaking lines of Indians as they filed through the gates of the coolie camp. All were cloaked in a dusty film of mud and poverty, but their optimistically raised voices revealed their relief and hope – a sharp contrast to what Sappani himself was feeling.

A few days ago, he had stood in those very same lines, with the very same hopes. Now he was a different man – a helpless man, with nothing and no idea how to move beyond this moment.

Seyan, his son, barely a year old, was asleep in his arms, his mouth open, his head lolling back. Sappani paced past the hospital shed – just a few rooms with a thatched roof – and back across the dusty courtyard. His eyes were fixed on the entrance, on every movement there.

Four days ago his wife Neela had been carried into the hospital shed, and the news since then had not been good.

The two-week journey on foot from the village of Polur in North Arcot on the Palar River in southeastern India, to Madras, this eastern port city on the Coromandel Coast of the Bay of Bengal had been difficult for Neela. Along with other recruits from their village, they had joined the arkatis, whose job it was to get as many Indians as possible to sign up for indentured labour in the British colonies. Only when they stopped and in the subdepots – small camps along the roadside – would Neela would have a chance to rest.

‘Let’s go back, Neela. Maybe when you are better we can try again.’ He thought about how he had begged her.

Sappani could still hear an echo of her voice, soft but determined. ‘There’s nothing left here in India for us, nothing for Seyan.’ She had said it so often that the doubt that Sappani felt would grow silent for a time.

During the day, to give Neela some respite, Sappani sometimes would leave his wife resting in a subdepot and take the baby with him into a nearby village. There, they would watch the villagers collect water or firewood and go about their lives.

Sometimes, though, he would stay in the subdepot, and watch and listen as the British-paid arkatis delivered their well-rehearsed speeches and promises to the crowds. ‘In South Africa, gold coins grow like chillies on trees and there’s work for every man and woman. Natal is booming,’ they said.

The gathered men and women always had the same questions. What work could they do? What would they earn? Could they take their families with them? And how soon could they return to home?

The men and women who joined were mostly pariahs, the lowest in the caste system. Usually, their jobs were menial: they worked on the lands owned by the superior Brahmin caste, swept roads and removed dead animal carcasses.

For the weavers, who for centuries had supplied their own countrymen with high-quality printed cotton fabrics, and whose exquisite floral chintzes, khassas and bandannas had been in high demand among the elite in England and Europe, the invention of the steam engine had been a death knell: not only did Britain impose punitive import duties on incoming Indian textiles, but exports of British goods to India increased, and cheap, machine-made cottons from Manchester flooded Indian markets. The weavers simply could not compete.

Those who planted and harvested their own food, tending modest patches of land that sustained extended families, and sometimes even having enough over to sell or trade, now too felt the pangs of starvation. The dry season had gone on for too long and food crops that had once thrived lay limp and burnt in the surrounding fields.

Sappani’s father had worked the land, and Sappani had done the same. A cane knife had first been placed in his tiny hands at the age of four, and he’d learnt quickly how to swing it. He’d been taught how to dig neat, endless furrows in hot fields and nurture the buds of the seedlings until they became stronger, from sun up to sun down, for as long as he could remember.

When the British government had introduced the land revenue system in order to milk as much money as possible from the peasants, families like the Mottais had found that they couldn’t grow enough food to feed themselves and pay the required taxes. Sappani had offered his labour to other landowners but the work wasn’t reliable and sometimes there would be forty men when only five were needed.

In the subdepots, once the women and children had gone to sleep, the men would talk among themselves. Perched on tree stumps and logs around the dwindling embers of a fire, they’d share their hopes and dreams. The poorest yearned for Natal, a place without castes, where everyone was mixed up together. Others spoke about steady work and the chance for their families to know what a full stomach felt like. They spoke about the other busy port, in Calcutta in northeast India, where thousands of Indians were also signing up and leaving for countries all over the world, to places that Sappani had not even heard of – Mauritius, Fiji, Guyana, Jamaica.

Sappani listened intently as the men shared stories they’d heard about life in Natal. Some told of a place of lushness and justice, where free men and women could raise their children in the sun, where the rain fell reliably and regularly to feed crops that sprang green and golden from the fertile soil, where just five years of hard work would earn for a committed indentured labourer a lifetime of contentment for himself and his family.

But others told of the rape of women and the natives who did not take well to the arrival of coolies, and of wages that were barely sufficient to keep a person alive, and which were docked for the slightest infraction, and of regular whippings.

‘It’s just a new way to have slaves,’ an older man with a grey beard said, shaking his head dolefully.

‘Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi – he’s a lawyer, a very good one, countered a young man with bright eyes. ‘He is fighting for the settled Indians in Durban to vote, even, and making sure those bastards treat us well.’

‘Let’s hope, bhai, that he wins, then,’ another man said and they all nodded in agreement.

Seyan stirred as he shifted in his father’s arms. Sappani gently rocked the little boy until his thick eyelashes met, fluttered, then were still. His breathing fell into a steady rhythm again.

There was some commotion in the courtyard. Two guards were roughly carrying a man out the gate, his legs dragging behind him as if they belonged to someone else. From the shouting, it was clear that he had failed the doctor’s examination and could not be allowed on the ship. Sappani watched as the man begged, then began to cry openly and angrily, his shoulders heaving as he kicked and spat like a cobra. A third guard threw his clothes after him and they slammed the gate shut. The man collapsed in the dust, weeping, clinging with his dirty hands to the fence around the camp.

A crowd had gathered, questions being asked and voices raised. Then word spread like a monsoon flood; the man’s testicles were enlarged, a certain sign of venereal disease.

Every recruit had to be checked by the doctors and nurses for diseases like cholera, chickenpox, dysentery and sexually transmitted infections, as well as anything that may mean they weren’t capable of hard work or, worse, might pass on infectious illnesses to the others. Only when they were checked and vaccinated were they permitted to join the coolie camp, as a prelude to being assigned a spot on an outbound ship. They would have to remain isolated in the camp until all available places on the ship were assigned to healthy Indians – the vessel wouldn’t leave the docks in Madras until it was full. During that isolation and waiting period, nobody could leave the camp, so that no new illnesses would be brought in when they returned.

Sappani winced with the memory of his own inspection. The British officials in the coolie camp hadn’t been slow to get the Indians to do exactly what they wanted them to do, flourishing sticks and threats with equal ease. Crude demonstrations showed that the Indians should remove their dhotis and cup their testicles for inspection. They had also checked Sappani’s teeth, ears and hands – callouses were a good sign; they showed that a man was accustomed to hard labour.

Once they had passed their medical inspection, the Indians were to stay in the camp, behind the high fences, under the watchful eyes of the soldiers. These rules were in place not only to prevent them from getting any illnesses, but also to ensure that the Indians who’d signed up didn’t give in to second thoughts before the ship was ready to depart.

Sappani had been given the all-clear and had been sent to complete the indenture contracts. The arkatis explained the conditions of the contract in the respective Indians’ native languages, their words sliding easily off their tongues into desperate ears. The men shuffled forward and signed the papers. Those who were illiterate confirmed their indenture with inky thumbprints.

The white officials doing the paperwork were sweating and ill tempered. Cramped inside the tents, pink and irritable, they had great difficulty with the Indian names. Names were often misspelt, or shortened, or simply omitted. Family names that had been used for generations were butchered using pens instead of knives or swords.

If this was going to be the start of something new for his family, Sappani knew he had to get his name recorded correctly. He had taken special care as he wrote out his details: Sappani Mottai, indenture number 140316, age 27.

He’d felt a surge of pride that he could spell his name and make sure that it was written down accurately. His ability to read and write had been a gift from the persistent Christian missionaries who had come to India in a steady stream, and whose sole purpose had been to convert the heathens and turn them away from their idolatry. Most families in Sappani’s village had sent their sons along to the mission schools when they were not needed in the fields. They listened to stories about Jesus and were taught to read using the Bible. Sappani was a quick learner and enjoyed sitting crosslegged under the neem trees, practising the English alphabet on his slate board.

His mind circled back to Neela. The doctor who’d inspected her hadn’t been pleased with her condition. She was too thin and very weak. After more questions, the doctor had put it down to her being undernourished. He’d given her medication and instructed her to stay in the medical tent so that they could keep an eye on her.

At first, this news had been welcome: Sappani had thought that she would get better and they would be together. However, since then he hadn’t been allowed to see her, and all he’d heard since was that she had been moved to quarantine as there was a risk of infection.

In the coolie camp the number of Indians rose and fell. More arrived and stayed, while some wore turned away. A few, once the initial excitement of being recruited had died down, and the temptingly shimmering goal of a new life across the black water had tarnished somewhat, realised that leaving India was a mistake and escaped from the camp at the first opportunity.

The arkatis had been instructed by their British bosses that forty per cent of the indentured Indians had to be females, as there were far too many men in Natal; they needed more women. The indentured men wanted to have families and often preyed on the wives of other men; this led to violent attacks and a spread of venereal diseases among the Indians.

The authorities were all for the indentured men setting up families, as not only did this mean that any children would be born into indenture as well, but the Indians seemed to work harder when they had little mouths to feed. And there was a fiscal reason for wanting women, too: for half the wages, they got workers whose smaller hands meant that they could pick the youngest leaves of the tea plants without doing any damage.

Single women who arrived at the coolie camp were often those who’d been shamed – widows, and those whose husbands no longer wanted them. They were mostly welcomed, but being locked away in the crowded camp while they waited for the ship to fill up, with the added indignity of the medical inspections, made many rethink their decision. Like shadows, they would slink away quietly at night, past the soldiers on patrol, never to be seen again.

Sappani found himself missing his old misery; at least then Neela had been nearby and Seyan had had his mother. Life in the village was familiar and that had been comforting. They’d barely been surviving on one paltry meal a day but at least they were together. Maybe this was punishment for thinking that he, as a pariah, could do better than a life of servitude.

The sun was sinking low and Sappani knew that soon the bell would ring to signal time to eat. If he wasn’t quick, Seyan would have to go without the daily ration of dhal and rice. Shifting the sleeping child to his other shoulder, he approached the hospital shed.

‘Can I see her, please? The boy needs his mother,’ he said to the nurse, who knew by now who he was.

‘She’s sick, and she could make you sick as well, and you have a baby to think of too,’ the nurse replied and turned her back to him as she continued to roll a pile of bandages.

Sappani stood there as if he hadn’t understood a word she’d said. Perhaps realising that she’d been a bit harsh, the nurse added, ‘This is the best place for her.’ She walked in through the curtains.

Outside, Sappani waited until Seyan screamed to be fed.

The next day, Sappani resumed his position outside the hospital shed. The doctor emerged, his grave face confirming Sappani’s fears. ‘Your wife is not getting better,’ he said flatly. ‘We tried but now she has dysentery too. It may be too late.’

‘But there must be something …?’ Sappani pleaded.

‘She should have been brought here straight away. Others could also get sick,’ the doctor chided. ‘We could have quarantined her and kept this from spreading.’

Sappani stared at him, dejected. He knew that whatever he said would make no difference.

***

Buy Across the Kala Pani here: Amazon

Read the full excerpt here: Google Books

Excerpt from ACROSS THE KALA PANI published by Penguin Random House South Africa. Copyright © 2022 by Shevlyn Mottai.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions