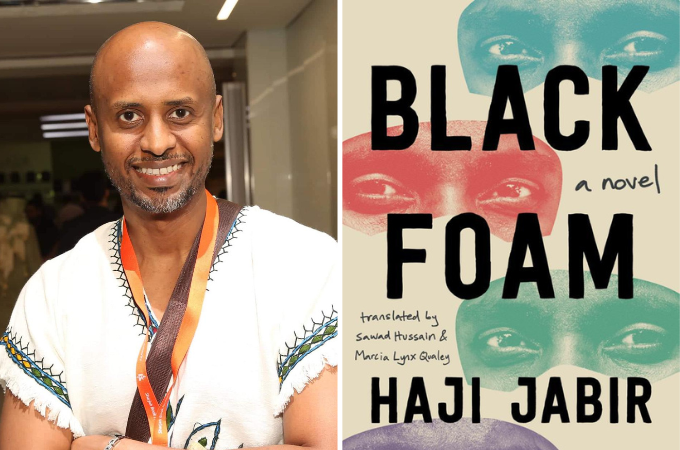

We recently got the opportunity to speak with Eritrean author Haji Jabir about his stunning new novel Black Foam, published earlier this year in English. He shared with us some fascinating insights into the inspiration behind this novel, writing moving characters into existence, and his growth as a writer.

Originally published in 2018 in Arabic, Black Foam is the first Eritrean novel to be longlisted for the International Prize for Arabic Fiction. The English publication is translated by Sawad Hussain and Marcia Lynx Qualey. Read our review of Black Foam here.

Jabir’s Black Foam is a moving novel about one man’s attempt to find home and belonging. On the run from his murky past, Dawoud journeys across North Africa and Israel, trying to assimilate into different groups by changing his clothes, religious affiliations, and even his name to fit in. However, prejudice follows him everywhere he goes, preventing him from finding home. Dawoud becomes a chameleon, shifting from one identity to another.

Haji Jabir is an award-winning Doha-based Eritrean novelist with five novels under his belt. His books have been translated into English, French, Italian, Hebrew, Kurdish and Farsi. Samrawit (2012) won the Sharjah Award for Arab Creativity, while The Game of the Spindle (2015) was longlisted for the Sheikh Zayed Book Award. His other published works include Fatma’s Harbour (2013) and The Ethiopian Rimbaud (2021).

***

Brittle Paper

Hello Haji. How are you? You’re currently based in Doha, right? What do you love the most about the place?

Haji Jabir

Hello, dear Brittle Paper, and thanks for interviewing me. In fact, my relationship with the place has always been ambiguous. As you may know, I have been since my childhood living in other people’s countries, after I left my homeland, Eritrea, as a child with my family, to escape the bombing that was affecting everything in my city, Massawa. Since then, I have been moving from one city to another on the margins of the place, as if my children and I were an extension of the kind of life that my parents lived, but with a fundamental difference, as they were always waiting for the imminent return to Eritrea, while this feeling is no longer as strong for me and my children.

However, there is a good thing about Doha, where I am now living my 14th year, as it is a peaceful city that gives me the distance I need, so that it does not harm me or intrude into my life. I feel that Doha respects my desire to live on its margin – this margin that I used to resist in the past, today I am fighting to stay in it; it is the peace that surrounds me far from everything. Is it the feeling of getting tired of waiting for things that don’t come? Well, maybe. Today, however, I feel a great reconciliation and even harmony with the fringes of the place and even life in general.

Brittle Paper

Congrats on the new book, Black Foam. It was originally published in 2018, but this is its first translation in English. How do you feel about English-speaking readers getting to enjoy the work?

Haji Jabir

Thank you for your kind remark. My works have already been translated into Italian, Persian and Hebrew, but what happened and is happening with Black Foam looks a little different which is surprising to me; the English translation made it sound like my first book ever, and I feel like this book is my actual beginning even though I started writing many years ago; is it the power of the English language? Perhaps! But what is certain is that I feel a little confused, because I existed as a writer before and after this book. Do I rejoice at how well the book was received, or do I resent it because it has become like a late birth certificate?

In general, and apart from all of that, the translation opened doors for more people to learn about my experience, and before that, to learn more about Eritrea and the Horn of Africa from the perspective I chose.

Brittle Paper

We’ve read the book and reviewed it, so we know what it is about. But there is something about hearing a writer describe their work. Let’s play a little game. Which five adjectives do you think describe Black Foam?

Haji Jabir

For my part, I will also play the game, but in my own way. I think that the last thing a writer can do is talk about his book, or explain his themes, goals, and the purposes he wanted to reach through what he wrote. Not because that might take away the suspense from the book, but rather because it restricts the prospects that the text may reach. Every reader who reads Black Foam is practicing another writing of the work, and comes up with ideas and personal meanings that I may or may not have included in the book, so it is illogical for me to confiscate all those prospects by mentioning what I meant. Let the readers come up with their own conclusions and thoughts on Black Foam without my input. I believe that the work that lasts long is the one that is open to endless interpretations, and as soon as I explain my text, I will kill any opportunity to interpret the text or understand it in a different way. You know, my friend, that when every reader reads a book, he reads himself, and I do not want to put myself between the reader and himself when he holds my book.

Brittle Paper

Dawoud leaves Eritrea and goes on an epic journey. He is in East Africa and then Israel, all the while finding belonging while running away from a past. What drew you to this story?

Haji Jabir

I often regard my novel Black Foam as a child of chance; I had not planned to write it, although I usually only write in obedience to a long plan right from the conception of the idea up to the methods of handling the narrative. However, Black Foam subverted all of that, scattered it, and imposed itself out of nowhere to become the urgent project that must be implemented, and it came into existence before a novel that was supposed to be completed according to my well-planned method of work.

The story began when I received news of the killing of an Eritrean refugee in Beersheba by Israeli forces. To be frank, this news could have passed like others, after causing some sadness and effect on my heart, with the abundance of Eritreans who get killed in their desperate flight from their homeland to different parts of the earth, on land and at sea. So, the news would not have attracted my attention much, had it not been for what accompanied it and what followed it. The victim was not the main target of the Israeli soldiers’ bullets, but rather it happened accidentally, while they were chasing a Palestinian suspected of stabbing, and it happened that the Eritrean victim was in the same spot, which made him flee as soon as he saw the soldiers, who in turn mistook him for the fleeing attacker, so they shot him and he died instantly.

Once more, despite all the grief, pain, and irony in this story, it probably would not have occupied my mind as it did after that, and the reason here is that I found both the Palestinian and Israeli sides could not deal with at the incident as they should have, but rather blamed the Eritrean young man for what happened to him. Some of the Palestinians even asked: “Why did he come to ‘our country’ in the first place?”, and among the Israelis were those who considered what happened to him as part of what could happen to any immigrant who risked entering ‘our country’ illegally. Then I found comments on social media that went beyond that and started insulting the dead young man, mocking him and even making fun of his worn-out shoes which were thrown next to his corpse.

Here I began to feel really angry, as the young man who left the hell of wretched conditions in his home country was killed in the “countries” of others, without even receiving mourning or sympathy. Perhaps if he had stayed in that hell, he would have found someone to cry over him. I hastened to write an article entitled “What is the Eritrean Doing in Israel?” In that article, I tried to explain the motives for leaving Eritrea and trespassing to other people’s countries, so that people might understand what is happening to us as Eritreans, but the article did not really subdue my fury, so I started writing the novel Black Foam.

However, apart from the spark that called me to write the novel, isn’t it possible that I glimpsed the great intersection between me and Dawoud despite the apparent difference? Did I write the story of Dawoud, or did I write my own story hidden behind Dawoud’s robe?

Brittle Paper

Dawoud is a shapeshifting character. He changes his name several times and feels compelled to reinvent himself. What went into creating his character?

Haji Jabir

I usually build my characters and the novel as a whole from a central question, which is: What if? This is a creative question that gives me the opportunity to test many possibilities and choose the most appropriate one. I also usually try to give the character the freedom to act according to the logic of the story. What can s/he do in this or that situation? In light of the outcome, the character is formed little by little. For instance, what would Dawoud do under the urgency of the idea of survival? This question gave me answers that were ultimately the features of his personality that you read in the story.

Brittle Paper

Tell us about Aisha. Every time Dawoud mentions Aisha, it is pure poetry. Moments when he talks about her are so captivating. What was different about writing her character?

Haji Jabir

As a matter of fact, a question arises for me here, in contrast to your question, which is: was Aisha an independent character that Dawoud fell in love with, or was she a character that he formed in his imagination and then became attached to? In fact, you will not find a definitive answer to this question in the novel, or let’s say each reader will come up with his own answer. I don’t know the answer either, and I wrote the novel under the influence of this uncertainty. Did Aisha satisfy Dawoud’s need for love, or did he create her so that he could find love? I think this may explain the way in which this character was written. In his view, she is too beautiful to be true without being completely true. All this made me keen to draw the character on the edge between truth and uncertainty.

Brittle Paper

As a writer, what aspects of Eritrean life do you seek to capture in your work?

Haji Jabir

Although the question sounds straightforward, I find that its answer is a bit complicated and involves many issues. I live outside Eritrea and I cannot return to it under the present ruling regime, and you can imagine that I am writing about my homeland from outside it, so my writing comes hungry for each and every detail of the people and the place, a personal hunger before being related to writing. That is why I always say that I test writing for myself before others; that I should fill my hungry soul with absent Eritrea before I convey its details to the readers. My hunger for Eritrea will remain, and I will try to quell it by writing, then I will find myself hungrier, so I will return to writing, and so on and so forth. If my writing succeeds in bridging the gap that separates me personally from Eritrea and the world from it, I will consider myself having achieved my goal by writing. In contrast to the darkness that surrounds Eritrea, every word is like a spot of light that fights against that darkness.

Brittle Paper

Sawad Hussain and Marcia Lynx Qualey did a fantastic job with the translation. What was it like working with them on the translation?

Haji Jabir

I have seen the amount of effort they exerted to reach the deepest possible understanding of the text, which is a complex and multicultural text. It includes Eritrea, Ethiopia, Palestine and Israel, and from all of these there are different languages, religions, temperaments, geography, information, etc. What was striking to me was this dedication to serving the text without interference. I felt Sawad and Marcia not as people but as translators, which is very important.

Brittle Paper

Have you read the English translation? What would you say is different about the textures of the English and Arabic texts?

Haji Jabir

My sense of the original text will remain linked to everything that is sentimental, unlike the translation, which goes towards accuracy and meaning. This applies to any translation of any book. Translation is an attempt to come close, but it will never arrive, and cannot be identical with the original. This does not detract from the value of translation for any book, but it is what usually happens and should be understood. Can we say that translating any book is another act of writing? Maybe!

Brittle Paper

Something we loved about Black Foam is that it gave us a taste of Eritrean literature. Tell us about Eritrean literature. Who are some of your most loved writers?

Haji Jabir

The spread of Eritrean literature was delayed due to many objective circumstances, the most important of which was the war in which everyone was involved in either fighting or being displaced, after which came a generation that collided with the outputs of independence, so it needed time to recover from its shock. What I am doing with the rest of my compatriot writers is trying to put Eritrean literature back on track, just as the first writers like Mohammed Saeed Nawed did. The good thing is that we are witnessing successive literary publications by Eritrean writers these days, which heralds a promising future. There are Eritrean names that write beautifully, such as Ahmed Omer Sheikh and Abu Bakr Kahal.

Brittle Paper

After five novels and awards, what has been the most fulfilling part of being a writer?

Haji Jabir

I tend to have a different answer every time I am asked this question, because there are really many reasons why I write, and they are endlessly reproducing. Writing happens for one reason or another, but what matters is that it happens eventually. This act, by the way, precedes its justification, i.e. we write and then strive to find out why this has happened.

I discovered that sometimes I write to restore my inner self and support my fragility in this world. And I discovered that I also write to avenge the disappointments that stick to the walls of the soul like an old tattoo, and I write to leave a mark, and I write to find answers to lingering questions.

I write because I am obsessed with the idea of illuminating my country, Eritrea, people, things, trees and roadblocks. This is my project that I chose from the very beginning and I am still following it. It is true that the ideas vary and the method of work is different every time, but the destination is the same. So I write the Eritrea I know and the one I don’t know. I write my love and hate for my homeland. I write what happened, is happening, and what I think will happen. I also write what I know absolutely will not happen at all.

Furthermore, I write because through writing I learn the true value of being a writer: to create a parallel world in which you are the owner of the decision, the beginning, the journey and the outcome, and you are the one who controls destinies and feelings, knows them and directs their repercussions. This very impossible possibility in life gives the writer some reassurance, as if he is trying life for the second time, and makes him more insightful about what will happen in one way or another. Therefore, as much as the writer rejoices at the completion of his text, some grief creeps into him, because he will leave his parallel world and return to face life with the loneliness he was in.

Brittle Paper

Thank you, Haji! It was lovely chatting with you today.

***

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions